Executive Summary

Despite a century of government-led efforts to improve the affordability of American housing, U.S. homeownership rates have barely budged in the last five decades. Four-fifths of Americans making less than $30,000 struggle to afford a home to rent. And Americans’ incomes have dramatically declined in relation to home prices. In 2008, the median after-tax household income was 37 percent of the median home price. In 2022, it was 18 percent.

The core problems are that federal policy has artificially increased demand for housing by encouraging excessive borrowing. On top of that, many policies at the federal, state, and local levels have artificially constricted the supply of housing. Constrained supply alongside subsidized demand equals higher prices.

In this paper, we review the history of U.S. housing policy since the 1920s, and offer six key recommendations for increasing the number of Americans who can afford to live in a community that will help them expand opportunities for themselves and their families:

- Reform zoning laws to encourage housing supply. Zoning is a 20th century solution to 19th century problems. Localities should relax or eliminate zoning restrictions and other rules that constrict the growth of housing supply. Building codes can keep housing safe and healthy without the complexities and costs of zoning regulations.

- Tie federal aid to local governments to reforms that increase supply. The federal government should focus its housing assistance on localities that have done the most to reduce the underlying cost of housing in their jurisdictions.

- Migrate away from building subsidized housing and towards Section 8 rental assistance. The federal government should more proactively assist families and move away from publicly funded housing projects and favor more flexible Section 8 housing vouchers that allow people to live close to their families or their workplaces. Publicly funded housing is expensive and reduces social mobility.

- Simplify the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program. Make it easier and less costly for developers to expand the supply of housing available to low-income renters.

- Reduce the systemic risk caused by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Today, government agencies like Fannie and Freddie dominate the secondary mortgage market. Because the market assumes that the government-sponsored enterprises will be bailed out by taxpayers, their assumption of mortgage default risk increases housing inflation and decreases the stability of the financial system.

- Reexamine the role of the Federal Reserve in creating housing bubbles. Near-zero interest rates, imposed by the Fed, created an incentive for large financial institutions to buy up residential real estate, increasing prices and decreasing affordability for low- and middle-income homebuyers. They also led to speculative buying by individual investors.

Ensuring that every American can afford a place to live comes down to two basic principles: increasing supply, and reducing artificial inflators of demand.

Introduction

The need for shelter is fundamental to the human condition, and to America’s economic aspirations. One recent survey found that 74 percent of respondents associated homeownership with the American Dream, a higher proportion than those who felt the same way about being able to retire (66%) or having a successful career (60%).

American policymakers have long sought to expand the ranks of homeowners, and of those who can afford a place to live. “True individual freedom cannot exist without economic security and independence,” asserted Franklin Roosevelt a 1944 speech proposing a “second Bill of Rights” which, he said, should include “the right of every family to a decent home.” In 1965, Lyndon Johnson declared that “every family [should have] the shelter and the security, the integrity and the independence, and the dignity and the decency of a proper home.” In a 2003 speech, George W. Bush said, “We want more people owning their own home. It is in our national interest that more people own their own home. After all, if you own your own home, you have a vital stake in the future of our country.”

This bipartisan consensus about the value of homeownership and of subsidizing shelter has led to hundreds of federal, state, and local initiatives, including hundreds of billions of dollars in subsidies for rental assistance, housing construction, and mortgages over nearly a century.

Unfortunately, it is far from clear that the policies we have adopted have worked. In 1965, at the dawn of the Great Society, the share of Americans who owned their own home was 63 percent. In 2022, the share is 66 percent.

While a dramatic expansion of government involvement in housing policy has been unable to meaningfully increase the share of Americans who own their home, we have seen a substantial increase in the price of U.S. homes. In 1961, the median U.S. household income after taxes of $5,557 represented 32 percent of the median home price of $17,361. In 2020, the median after-tax income of $74,949 represented just 22 percent of the median home price of $337,500. In 2022, the median home price is $440,300.

Housing has long been — and continues to be — the single greatest contributor to Americans’ cost of living. For the median U.S. household, housing represents 35 percent of consumer expenditures. For families in the bottom quintile, housing represents 43 percent of consumption: a greater share than food, health care, and clothing combined.

The past century of government housing policy can be classified into seven categories:

- Zoning and permitting. Restrictions on the placement and construction of residential housing, through local ordinances, slowed the growth of new housing construction and housing renovation.

- Public housing. Beginning with the New Deal, the federal government began building government-owned and operated apartment buildings to house those who otherwise could not afford it.

- Rental assistance. In the 1960s, the federal government significantly increased its efforts to subsidize the cost of renting housing by administering vouchers through local authorities.

- Civil rights legislation. The Fair Housing Act, a component of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, barred discrimination in the sale, rental, and financing of housing based on race, religion, and national origin. Provisions barring discrimination on the basis of gender, family status, and disability were later added.

- Subsidies for housing construction. Programs like the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit, or LIHTC, established in 1986, subsidize the construction of housing rented at below-market rates.

- Subsidies for borrowing the money to purchase homes. Through various government-sponsored entities, like the Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae), the federal government heavily subsidizes the ability of Americans to borrow money to purchase a home. These subsidies do not take the form of cash payments, but rather by insuring mortgages from the risk of default, thereby incentivizing banks to lend more money at lower interest rates.

- Federal interest rate controls. The U.S. Federal Reserve has long had the power to influence the interest rates that drive borrowing throughout the financial system, including in the housing market. These powers expanded after the 2008 financial crisis. Since 2008, the has Fed kept interest rates at historic lows, encouraging real estate borrowing.

Of these seven categories, five — zoning and permitting, rental assistance, subsidies for housing construction, mortgage subsidies, and federal interest rate controls — have had a significantly inflationary effect on housing prices. Zoning and permitting restrictions make it harder and costlier to build new housing. The Fed’s unusually aggressive low-interest-rate policies since 2008 have driven housing prices to new highs. Fannie and Freddie were incentivized to backstop risky mortgages, knowing that taxpayers would eventually be liable for bailing them out. And while helping low-income Americans afford a place to live is a worthy cause, the specific design of federal rental assistance and LIHTC effectively rewarded localities for making their housing markets more expensive.

In 2018, according to the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies, nearly half of all renting U.S. households were paying over 30 percent of their income for rent, with one-quarter paying over 50 percent of their income for rent. The burdens were even more severe for those making less than $30,000 per year.

At a time of high inflation, there are few problems more important to examine than the decline in the affordability of renting and homeownership. In this paper, we examine the past 100 years of U.S. housing policy and identify opportunities for reform.

Part I: A Century of U.S. Housing Policy

The birth of zoning

Euclid, Ohio, named after the Greek mathematician, is today a suburb of Cleveland on the shores of Lake Erie. It was one of the first towns created in what was called the Western Reserve, an area of what would become the state of Ohio owned by the state of Connecticut. Largely agricultural, at the beginning of the 19th century, the city began to grow, increasing in population and interest from railroad investors.

By the beginning of the 20th century, the notion of growth, outside investors, and the future of the town would come to a head when the city created regulations to limit the development of land owned by the Ambler Real Estate Company to prevent the railroad. Ambler sued, and the resulting legal battle and 1926 Supreme Court decision, Village of Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co., forms the basis of today’s local zoning laws.

Zoning ordinances proliferated in the early 20th century. Both the number of U.S. municipalities with zoning ordinances, and the share of the U.S. population living under such ordinances, exploded in the 1920s. (Source: J. Hartley, adapted from Zoned Municipalities in the United States, 1933)

Regulating the use of private land and the suburb

It might seem surprising that an almost century-old legal decision would still have such a strong effect on urban planning, land use, and ultimately housing policy. But the decision solidified two central ideas, each dependent on the other. First, local governments have the power to decide the use of private land, including how much and where housing can be built. This means that a small group of elected officials can determine the supply of housing in a city, a decision that has a profound effect on price when demand rises. Second, segregation of uses — housing here, industry there, and retail and commercial over there — required a subsidized transportation system.

One might think of Robert Moses as the father of the suburb, an urban form of two- or three-bedroom houses on big lots linked by “free” public roadways. However, together with government backed mortgages, it was really zoning that enabled post-war Americans to aspire to owning their own home with a mortgage, a job they would drive to in the morning, and drive back to at the end of the day. Importantly, the value created by inflation over time meant that owning a home like this was building wealth. When the family got bigger or older, it could be sold for a profit, money that could be used for a new, bigger home or a home for children.

Taken together, government control of when and where and how housing was built, along with accessible financing for otherwise out of reach capital construction, formed an economic entitlement system; Americans felt that if they worked and saved, they should be able to buy their own home, ensuring the welfare of themselves and their children. By the latter half of the 20th century, home ownership became associated with American way of life. Politicians campaigned on homeownership as on a par with mom and apple pie, something that every American should aspire to.

Zoning ordinances by municipal population. Both large and small municipalities adopted zoning regulations. (Source: J. Hartley, adapted from Zoned Municipalities in the United States, 1933)

Segregation of use becomes segregation of people

It is important to note that with government financing through what was called the Home Owners Loan Corporation, or HOLC, came requirements and risk assessments about what loans would be backed and which would not. The HOLC favored suburban housing and made specific assessments based on race, designating white areas as eligible for loans for housing and Black areas ineligible, setting up what would be known as “redlining.” Covenants were also established and attached to title in many communities preventing the sale of a home to Black families. These interventions by the federal and local governments were reinforced by zoning which tended to concentrate more dense development in urban cores. The segregation of the use of land became, through zoning, the segregation of people by race.

Sprawl, growth management, and planning

During the 1970s and 1980s, when awareness and concern about the environmental impacts of increasing population and growth began to rise, so did opposition to what came to be called “sprawl,” a new name for what had generally been called, in a positive way, suburbs. The opposition to sprawl, like so many relationships between advocates in housing, brought together single-family neighbors worried about their investment and environmentalists worried about the impact of new growth on water and air quality.

Together both groups urged the government to limit when and where housing could be built. But as long as jobs and population were on the rise the problem was where would housing go to meet the need, especially in growing cities. The professional planner began a renaissance in America; the answer to addressing the conflict between new growth and the desire of existing homeowners to preserve the value of their asset would come through planning, especially plans that used zoning.

The birth of NIMBYism

Without a doubt, the single most important reason that existing homeowners resist the construction of new housing, even miles from their own home, has to do with their worries about the impact of new housing construction on the value of their asset. The pattern is typical. A proposal that would change zoning to allow more housing is set forth, and neighbors angry about the changes show up and make a few common arguments:

- Not being properly informed or included;

- The problems that will be created with parking;

- Impacts on things like tree canopy or views; and

- People who oppose new housing almost always argue they are against it because it is too expensive.

Occasionally, early in this cycle, concern about asset value will be stated openly, as it is on the website of a group called Low Density Ohio that opposed modest increases in the number of housing units in Cincinnati through changes in zoning: “Single-family homes provide the resident with a greater sense of ownership, and real responsibility to maintain one’s property. With home ownership, you are owning a piece of your, city, state, and nation!”

Thus, most such proposals fail, largely because people opposed to new housing have time, money, and most importantly, vote. Changes to zoning codes inspire tremendous controversy and local elected officials desiring to avoid that, usually end up favoring the people who have the time and resources to show up and press them not to make changes.

The New Deal and the birth of federally backed mortgage finance

The massive unemployment of The Great Depression — peaking at nearly 25 percent in 1933 — also resulted in mass mortgage default and foreclosures where a significant number of American households lost their homes.

In response, in 1938, through various amendments to the National Housing Act, the Federal National Mortgage Association (or Fannie Mae) was established to guarantee mortgages through buying mortgages from depository institutions, principally savings and loan associations, which encouraged more mortgage lending and effectively insured the value of American mortgages by the U.S. government.

In the aftermath of the Great Depression, when the federal government undertook dramatic reforms to limit foreclosures and stabilize the housing market, the government attempted to overhaul property appraisal practices, establishing in 1933 the Home Owners Loan Corporation.

The HOLC drew maps for over 200 cities as part of its City Survey Program to document the relative riskiness of lending across neighborhoods. Neighborhoods were classified based on characteristics like housing age and price, as well as on non-housing attributes such as residents’ race, ethnicity, and immigration status. The lowest-rated neighborhoods (which also happened to have large fractions of African-American residents), where borrowers were denied access to credit, were drawn in red — a practice now called “redlining.” Academics like Aaronson, Hartley, and Mazumder (2021) have found that the HOLC redlining maps reduced home ownership rates, house values, and rents and increased racial segregation in later decades.

The Great Society transforms U.S. housing

Federal housing policy was transformed by a series of laws enacted under the “Great Society” initiatives of President Lyndon Johnson. These laws — the Housing Act of 1964, the Housing and Urban Development Act of 1965, the Department of Housing and Urban Development Act of 1965, the Fair Housing Act of 1968, and the Housing Act of 1968 — continue to define the federal housing policy landscape today.

Prior to the Great Society legislative fusillade, federal housing policy had been defined by the Housing Act of 1937, sometimes called the Wagner-Steagall Act, which authorized the federal government to fund public housing built by local government housing agencies. This emphasis on local control enabled many localities to restrict access to public housing for racial minorities, especially in the Jim Crow South, in combination with the “redlining” phenomenon described above.

Just as consequentially, in order to respond to concerns that public housing would compete with private housing, only the poorest of the poor were eligible for such housing. The end result was that the conditions in New Deal housing projects became as bad as in the slums that President Roosevelt had aimed to wipe out.

Housing, then as now, was seen as a major driver of economic and social inequality. As immigrants and African Americans moved into large cities before and after World War II, the condition of urban housing also became a factor in racial inequality. In the early 1960s, President John F. Kennedy had been developing a housing agenda in close collaboration with Robert Weaver, whom Kennedy had appointed to run the U.S. Housing and Home Finance Agency (HHFA). In this role, Weaver became one of the most impactful Black policymakers of the 1960s.

But Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963. Five days later, Johnson — his successor — vowed to preserve and advance Kennedy’s policy priorities, including housing, declaring that “today, in this moment of new resolve, I would say to all my fellow Americans, let us continue.” In March of 1964, Johnson went further, calling for “total victory” in a “national war on poverty,” with the goal of enabling every American to afford a decent home. After the 1964 presidential election, Johnson was sent back to the White House with Democratic supermajorities — a 155-seat majority in the House of Representatives, and a 68–32 majority in the Senate — giving him the opportunity to enact this agenda.

The debate over rental assistance

Influential activists and stakeholders were divided on the White House’s housing agenda. Left-wing activists, building on the New Deal legislative tradition, sought to expand the role of government-owned and operated housing projects. Private sector developers, on the other hand, saw public housing projects as encroaching on their role in building housing that low-income Americans could afford.

Johnson and Weaver were eager to overcome those divisions by subsidizing private-sector housing, in particular by advancing “rent certificates” that low-income Americans could use to obtain affordable housing. Rent certificates were first proposed in the 1930s by trade associations like the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, The National Association of Real Estate Boards, and the National Association of Home Builders, who saw rental assistance as a more economically and socially effective alternative to public housing projects. (It was also clearly in their economic interests to support private-sector-oriented housing assistance, if the clear alternative was public housing projects that would crowd out their own.)

The left-wing activists, in turn, were hostile to private-sector involvement in housing assistance, and argued that rental assistance would benefit slumlords at the expense of the poor. As African Americans migrated to cities, southern Democrats feared that housing aid would geographically integrate Black Americans into the broader population. And Republicans saw rental assistance as socialistic; then-House minority leader Gerald Ford described one Johnson initiative as a “radical revolutionary rent-subsidy gimmick.”

Despite all the opposition to rental assistance from both the left and the right, Johnson continued to push for it, and in 1965, Congress narrowly passed the Housing and Urban Development Act of 1965, which contained rental assistance provisions, albeit ones that had been watered down by the bill’s congressional skeptics. After the midterm elections of 1966 narrowed Johnson’s majorities, Congress significantly reduced appropriations for rental assistance.

Congress eventually revived rental assistance under President Richard Nixon, enacting the Housing and Community Development Act of 1974, which created what is now known as “Section 8” housing assistance, by amending Section 8 of the Housing Act of 1937.

On April 4, 1968, Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated. Riots erupted in over 100 U.S. cities. Soon after, President Johnson signed into law the Civil Rights Act of 1968, Titles VIII and IX of which comprised the Fair Housing Act, prohibiting racial discrimination in the sale, rental, or financing of housing. A second law, the Housing Act of 1968, established subsidies for private developers to build low-income housing.

In total, the effect of the Great Society legislation was to dramatically expand the federal role in subsidizing housing for low-income Americans, primarily by increasing subsidies for rental assistance. Prior to the Great Society, federal housing assistance for low-income Americans was primarily in the form of subsidizing public housing. Afterwards, the federal government focused increasingly on rental assistance.

Federal housing subsidies today

Today, there are over two dozen major federal programs that subsidize housing for low-income and vulnerable populations, amounting to $68 billion in non-COVID housing assistance, aiding 4.3 million households, including 3 million on Section 8 assistance:

Tenant-Based Rental Assistance Program (2021 spending: $25 billion). Tenant-based rental assistance, also known as Tenant-Based Section 8, is the largest federal housing program, enabling low-income households to gain subsidies for private rental housing, after they pay 30 percent of their income for rent. Section 8 vouchers are administered by local Public Housing Authorities.

Project-Based Rental Assistance Program (2021 spending: $14 billion). Project-based rental assistance, also based on Section 8 of the Housing Act of 1937, works similarly to tenant-based assistance, except for the fact that the subsidies are sent by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) directly to the landlord or property owner. Congress ceased issuing new project-based contracts in 1983, but grandfathered in existing units.

Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (2021 spending: $11 billion). The bipartisan Tax Reform Act of 1986, passed by a Democratic House and a Republican Senate under President Reagan, established the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit, or LIHTC, which has become one of the largest federal housing programs.

Public Housing (2021 spending: $4 billion). Under Section 9 of the Housing Act of 1937, the federal government helps to subsidize local government-owned and operated housing. Tenants pay 30 percent of their income to the housing operator, and HUD picks up the rest. HUD also supports capital improvements in public housing projects. Today, approximately 970,000 households live in public housing, managed by 3,300 local housing agencies. More than half of public housing tenants are elderly, disabled, or both.

HOME Investment Partnerships Program (2021 spending: $1.5 billion). The HOME program, first authorized under the National Affordable Housing Act of 1990, provides block grant funds to states and localities to fund production of new housing units, housing rehabilitation, homeownership assistance, and time-limited rental-based assistance.

Other federal programs ($14 billion). The federal government also subsidizes a smattering of smaller, usually sub-$1 billion-per-year programs, including the Choice Neighborhoods Initiative, the Rental Assistance Demonstration, the Housing Counseling Assistance Program, Section 202 Supportive Housing for the Elderly, Section 811 Supportive Housing for Persons with Disabilities, the Section 521 Rural Rental Assistance Program, the Section 236 Rental Housing Assistance Program, the Section 236 Rental Assistance Payment Program, the Rent Supplement Program, the Housing Trust Fund, the Private Activity Bond Interest Exclusion, the HOME Investment Partnerships Program, the Self-Help Homeownership Opportunity Program, Homeless Assistance Grants, the Housing Opportunities for Persons with AIDS program, Native American Housing Block Grants, Native Hawaiian Housing Block Grants, the Affordable Housing Program, the Section 235 Mortgage Insurance and Assistance Payments for Homeownership Program, and Rural Housing Assistance Grants.

The GSEs: Fannie Mae, Ginnie Mae, and Freddie Mac

The United States remains virtually the only country in the world to have a residential mortgage system where 30-year maturities are the dominant norm, largely thanks to institutional government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) like the Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae), the Government National Mortgage Association (Ginnie Mae), and the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac).

The GSEs insure mortgages against borrower default, effectively subsidizing the interest rates with which banks can lend to real estate borrowers. (Banks charge higher interest rates to those with higher default risk, and lower interest rates to those with lower default risk; if GSEs — and thereby taxpayers — are insuring the loans, banks face lower risks of default.) Despite the 30-year fixed rate mortgage norm, most mortgages in the U.S. do not last for 30 years (i.e., they do not reach maturity), as many households move to new homes before 30 years have elapsed, and must pay off their old mortgage loan using the proceeds of their sale. As a result, the average mortgage loan is outstanding for approximately 7 years.

In 1968, to increase home ownership and the availability of mortgage finance, Fannie Mae — the New Deal creation — was split into two entities: the current version of Fannie Mae and the Government National Mortgage Association (Ginnie Mae). In 1970, Congress then established the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac). In 1968 and 1970, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac respectively became public companies by issuing public stock.

Shortly after Fannie and Freddie became public, the mortgage market was becoming securitized. In the 1970s and 1980s, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac issued their first mortgage-backed securities which enabled mortgage pass-through through mortgage bonds that could hold mortgages diversified by maturity, region and prepayment.

These actions seemed modest at the time, but over time they came to dominate the way Americans purchase homes — and much more.

The mortgage market after the 2008 financial crisis

The vast majority of U.S. homebuyers today require a mortgage to finance their home (only ten to 12 percent buy with no debt), and in the 21st century almost all U.S. mortgages are backed by the GSEs.

The housing crisis of 2008 left a noticeable mark on the U.S. mortgage market. The decline in real estate prices put many overextended households into insolvency and foreclosure, resulting in the insolvency of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which were nationalized by the federal government. This put most of the country’s mortgages on the balance sheet of the federal government. In addition, private-label, non-agency mortgage-backed securities almost entirely disappeared, along with various other types of exotic mortgages securities, as exposure to several mortgage derivatives and mortgage-back securities put investment banks like Lehman Brothers into bankruptcy. Other banks became insolvent to the point where they were ultimately sold to larger commercial banks: Merrill Lynch and Countrywide acquired by Bank of America, Wachovia acquired by Wells Fargo, and Bear Stearns and Washington Mutual acquired by J.P. Morgan.

As the real estate market slowly recovered in the aftermath of the Great Recession, household balance sheets also began to recover and regain lost ground. Meanwhile, a Democratic Congress and President passed and signed the Dodd-Frank Act in 2010, establishing minimum capital requirements (e.g., the solvency ratio and liquidity coverage ratio) and annual stress testing (D-FAST) for banks. These regulatory actions ultimately reduced leverage significantly on the part of banks and arguably prevented banking crises from happening again when the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted financial markets in 2020.

Trends in the price of U.S. housing relative to income

Unfortunately, most rental housing price data is proprietary and difficult to find in the public domain. The data used for this analysis was gathered from iPropertyManagement, Zumper, Willow, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Saint Louis, commonly referred to as FRED. Over the last 20 years, housing prices have tracked steadily upward, rising about an average of five percent year-over-year, with two big exceptions: the period of 2007 through 2011 and in 2021. In the first period, as discussed above, there was a serious housing-related recession and many homes that were purchased with risky mortgages were lost. The burst of demand for housing in 2021 is still something of a mystery, with the pandemic probably playing a role, perhaps encouraging people who were in quarantine to find more space or to relocate.

For ten out the 20 years from 2000 to 2020, rent inflation outpaced wage inflation. The relationship was uneven, with the biggest gap in 2010, when rent inflation was 2.28 percent and wage inflation was -1.51 percent. This gap was also the result of the recession. Median income in the country increased about nine percent, rising from $61,553 in 2000 to $67,521 in 2020. Even though average rents doubled from $592 to $1,164 during that time, most households were paying, on average, less than the normative 30 percent of gross monthly income on housing.

So, what accounts for the housing crisis that is so often mentioned in the media, by advocates, and politicians? First, housing prices are distributed unevenly — generally by geography. In Topeka, Kansas, for example, the average household income is about $50,000 and average rents for a one-bedroom apartment are near $600. In 2020, homes sold for about $120,000, well within the range of what might be considered “affordable.” Meanwhile, in Seattle, median income for a household is about $52,000, but average rents for a one-bedroom apartment approach $1,700. That is $300 more than the 30 percent of monthly income generally considered “affordable.”

Second, averages are deceptive as an indicator of people’s relationship to price. Often, affordable-housing advocates tout a particularly sympathetic job title like teacher, cite the average income of a teacher in the area, then point to the gap between the average rent and those wages. The problem with that, of course, is that some teachers earn more and some less than the average and not all apartments or living arrangements are priced the same. Also, new housing — just like new clothes or a new car — is usually more expensive than existing, older housing. A burst of new housing construction, which ultimately alleviates price pressures on existing housing, can temporarily mean higher average prices.

Third, affordability is a qualitative relationship to price. That is, whether something is affordable or not depends on how an individual feels or manages to pay for something. A recently graduated college student might be doing well spending half her pay check on housing because she has very few expenses, while a single mom with two kids might be paying 29 percent of her income and still be struggling. If the two women in question were earning the same amount of money and living in the same census tract, the college student would show up as “cost burdened” while the mom would not.

Finally, people in markets make choices. Even families earning less money might choose to live in a suburb and commute to work because they like the schools. This family might be managing housing costs well, but see big opportunity costs from the commute.

All of this is not helped by a continual effort to make the problem seem even worse than it is. Every year, the National Low Income Housing Coalition releases a report that shows the gap between some worker’s wages and the cost of rent for a two-bedroom apartment. This kind of selective use of data does not help clarify the problem but does adds a sense of panic to the discussion. U.S. Census survey data by itself also does not help. If gaps between wages and housing costs get wider, is it because housing got more expensive or because wages went down?

“Cost burden” methodology is deeply flawed, taking survey data, extrapolating it to regions, then taking the resulting figures and designating them as the “affordable housing gap.” For example, in Cincinnati, this method has led to the claim that the city needs to build 44,000 units of subsidized housing, a number that is absurd: The entire Metropolitan Statistical Area, and areas encompassing numerous jurisdictions, permitted 64,000 of housing — all typologies, public and private — from 2010 to 2020. Cincinnati has a total of only 300,000 people. Building 44,000 units there would be enormously expensive, take a long time and, in the end, be a disproportionate use of resources.

We need better measures of housing costs in the United States, ones that take into account other costs that households have to pay, and also whether or not housing permitting and production is keeping up with population growth.

Part II: Policy Recommendations

1. Encourage growth in the supply of housing

While the Supreme Court’s Euclid decision established a reasonable test for land use — we shouldn’t let the pigs into our parlor — the formulation is no longer adequate for the world we live in. With an economy based in technology not industry, environmental concerns, a global pandemic, and an uncertain future, zoning straitjackets the ability of local economies to respond to growth with more housing quickly. By empowering incumbent property owners with process, arcane rules, and long permitting times, zoning advantages people who are already have homes, rather than making room for new people.

A growing number of housing advocates are embracing the concept of “yes in my backyard,” or YIMBY, as a framework for reforming single-family zoning mandates and other rules that prevent the growth of multifamily homes and apartments. Prudent building codes ensure health and safety and are important to maintain. But otherwise, neighborhoods can and should be a diverse mix of density and typology driven by need, more than by aesthetics or the desire of single-family property owners to keep their property values high at the expense of others in the community. Prudent building codes keep buildings safe, whereas zoning mostly drives up costs in a way that segregates people and complicates transportation.

2. Tie federal aid to local governments to reforms that increase supply

The Tenth Amendment to the United States Constitution established that “powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.” Accordingly, land use and zoning, which impact housing development, construction, and operation are outside of federal control. States generally have devolved almost all land use and zoning authority to city and county governments, with the exception of some environmental statutes that affect land use. Since the Euclid case, most courts have deferred to local land use decisions, affirming the power of local governments to determine when and how housing gets permitted and built. Efforts to challenge these laws on the basis of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments — typically called property rights challenges — have mostly failed.

As a result, over the last century, critical land use and zoning laws have been made in patchwork fashion reflecting highly localized political and economic interests. The federal government’s ability to influence all these localities is limited primarily to tying strings to funding for housing subsidies or other federal funds. Both the Trump and Biden administrations sought to do just that, with little success. The White House recently touted $6 billion in transportation funding it suggested was tied to “location-efficient housing.” But upon closer examination, the new rules are incremental in nature.

What, specifically, could the federal government influence by way of its significant funds and tax credits? It could condition federal housing and transportation assistance to state and local governments on regulatory reforms for efficient land use, such as:

- Significantly reducing land use restrictions for new housing. This would include local audits and assessments of permitting times and costs, as well as how those could be reduced to generate savings for consumers.

- Preempting Mandatory Inclusionary Zoning (MIZ). States should prohibit their localities from imposing fees on the production of market-rate housing for the purpose of generating fees for non-profit subsidized housing. MIZ policy penalizes the production of market rate housing, boosts costs for consumers, and is inflationary; it is also a kind of “pay to play” scheme that is inappropriate.

- Preempting rent control. Price controls in housing have the opposite effect as intended — they end up raising prices. To get federal funds, states that allow rent control should roll it back, and those that do not should prevent local governments from imposing it.

- Reducing tenant-landlord laws that increase risk. Regulations that try to tip the scale in favor of consumers end up creating more risk for people renting their private property; the only way to offset these additional risks is by increasing rents. Interventions like banning credit scores, eliminating screening, and banning eviction in the winter all increase risks and costs which end up raising prices or eliminating supply when smaller housing providers can no longer manage the risks.

- Reducing land use and building code restrictions. Local jurisdictions should be required to review and eliminate impediments to the kind of innovation that results in lower costs housing. For example, jurisdictions that eliminate rules to allow more backyard cottages, smaller apartments, and more infill development in single-family neighborhoods should be rewarded.

- Reducing or eliminating parking requirements in new housing. Parking adds cost to housing, and if consumers want to pay for it, developers will include it. When consumers don’t demand parking, it shouldn’t be required. Currently millions of dollars are wasted building parking that is required but not asked for by consumers, and that means higher housing costs.

- Reducing or eliminating public design reviews. Housing production is too important to be governed by boards fretting over fenestration and the color of Hardy panels. No federal funding should flow to any jurisdiction that requires design review for the development of new housing.

- Phasing down the reward for local home price inflation. Because Section 8 housing assistance is tied to one’s income relative to the local price of housing, localities that drive up housing prices through supply restrictions end up receiving taxpayer subsidies to do so (because the higher cost of housing is offset by higher Section 8 subsidies). Congress should consider migrating Section 8 assistance to a flatter model, in order to reward low-cost housing markets over high-cost ones.

Taken together, these kinds of changes would result in more market supply of housing, faster response by housing producers to surges in demand, and ultimately, to more stable prices for consumers. This would mean fewer subsidies would be needed and those subsidies could go further and deeper for those with greater needs.

3. Move away from building publicly funded housing to Section 8 rental assistance

For the programs and resources that the federal government does directly control, it is worth reconsidering where federal aid is most successful at increasing the number of Americans who can afford to rent or own a home.

The least inflationary form of housing subsidy is rental assistance: the form of housing aid most meaningfully established by Lyndon Johnson. Rental assistance can be targeted to lower-income households, limiting its inflationary effects.

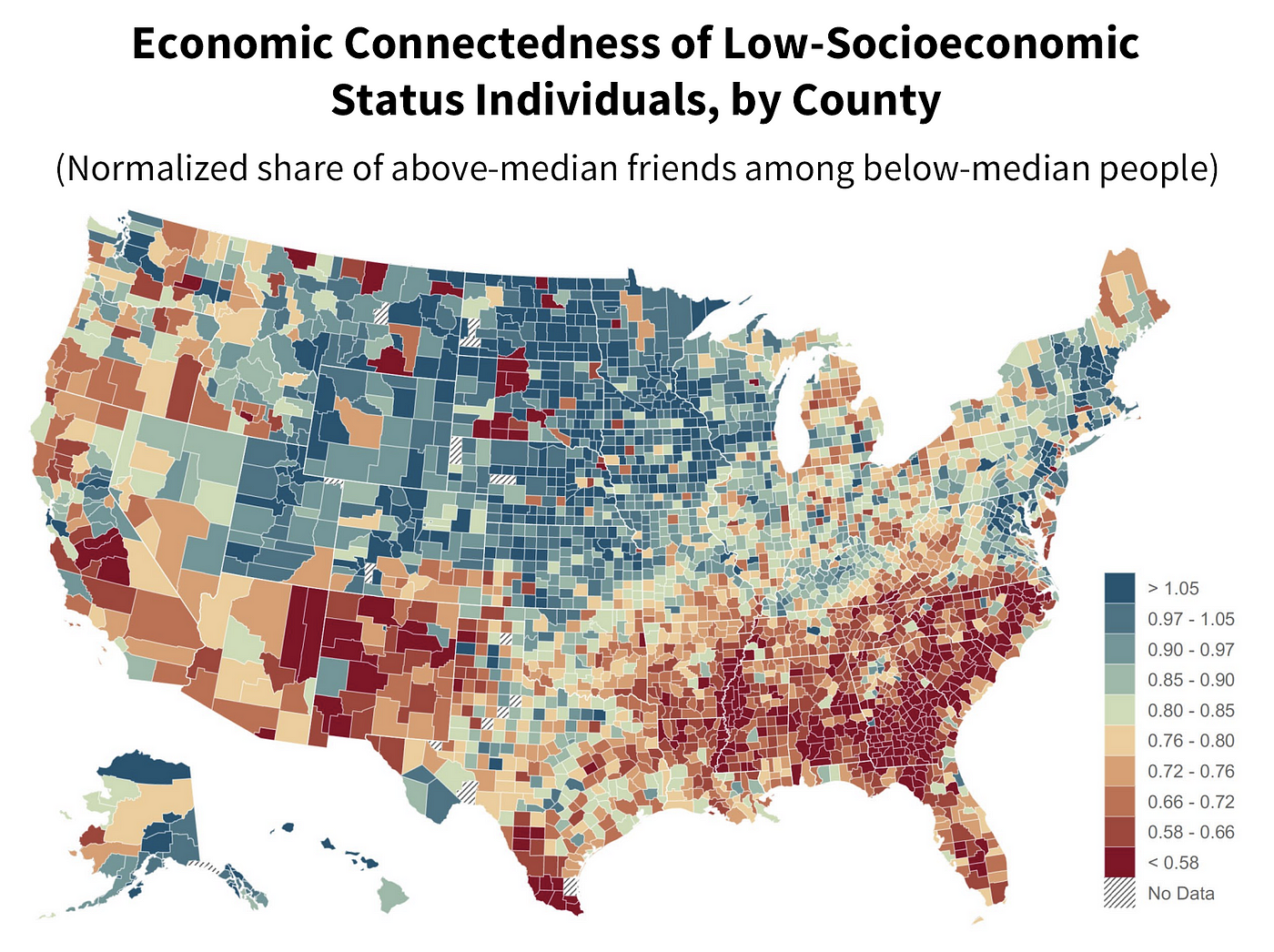

Rental assistance, such as Section 8 vouchers, has other significant advantages over public housing projects. First, because rental assistance can be used with any participating landlord, it enables program participants to live closer to their extended families or to their workplaces, in contrast to public housing. Second, rental assistance can be used to live in older housing stock, whereas expanding public housing involves costly new construction. Third, public housing concentrates low-income individuals into an economically segregated community, diminishing their social capital. New research from Raj Chetty and colleagues drives home the value of social networks that include both low- and high-income individuals. Concentrating poverty in public housing denies low-income individuals that opportunity.

As much as possible, policymakers should consider consolidate federal housing assistance to low-income Americans into Section 8 vouchers, and improve the utility of Section 8 by removing obstacles that disincentivize landlord participation, especially burdensome inspections. Vouchers should work like cash as much as possible, and once a household qualifies, they should be able to use the voucher where that household is currently living and paying rent.

One way to improve the reliability of the Section 8 program — and many other forms of federal assistance — is to use “stablecoins,” blockchain-based versions of cash pegged to the U.S. dollar, for tenant-landlord transactions. Because stablecoins are traceable on a distributed ledger, the reduced risk of fraud would enable the federal government and local housing authorities to reduce the burdens of a traditional oversight regime.

4. Simplify the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program

The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program, or LIHTC, is a well-intentioned program designed to incentivize developers to build housing that is rented to low-income individuals at below-market rates. If developers’ projects qualify for LIHTC, they receive tax credits which, in theory, enable them to offer the below-market rents.

Unfortunately, in reality, the LIHTC program is unwieldy and complex, limiting its potential and needlessly increasing the cost of developing LIHTC housing. For example, local governments can require that LIHTC developers pay above-market wages for project workers, driving up project costs and reducing the incentive to build. A study by the State of Washington found that after construction costs, “costs associated with financing, permitting, impact fees and reserve requirements” ate up about nine percent of project budgets and that another four percent of project costs were “related to federal, state, or local government regulations such as prevailing wage, zoning, green building standards, and local government parking and design standards.”

Policymakers could make LIHTC easier to use for urban infill projects by for-profit developers. For example, credits could be applied to a project in exchange for a 20 percent set-aside of units for people earning less than 60 percent of area median income (AMI). This is a lower threshold of below-market units than is currently specified under LIHTC.

5. Reduce the systemic risk caused by Fannie and Freddie

The dominant role of Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae gained widespread attention during the financial crisis of 2008. And yet, the three federal giants represent 93 percent of the mortgage-backed securities market today. While many believe that the GSEs have helped expand access to homeownership, the evidence suggests that the GSEs, by artificially stimulating housing demand, have also contributed to home price inflation, largely offsetting their ability to increase access to homeownership.

There have been several failed attempts to re-privatize Fannie and Freddie, most notably during the Trump administration. Policymakers have recognized that government conservatorship of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac does not mean that taxpayers cannot suffer further losses and that the GSEs are not taking on risk. In fact, any losses that Fannie and Freddie now incur will be directly passed onto the taxpayer.

One widely perceived pre-condition to the re-privatization of GSEs is imposing capital rules on them as they have maintained fairly high debt levels since the financial crisis. The Dodd-Frank capital rules instituted in 2010, originally meant to limit leverage on the part of financial institutions, did not apply to GSEs but rather only to private banks (with a particular emphasis on global systemically important banks or “G-SIBs”).

At the outset of the Trump administration, Fannie and Freddie, with $6 trillion of mortgage assets on their combined balance sheets, had the ability to own $1,000 in assets for every dollar of equity on their balance sheets (only holding $6 billion in equity with $6 trillion of liabilities), implying a 0.1 percent capital ratio. By comparison, private U.S. banks have been required to meet standards of an 8 percent capital ratio (even before additional capital buffers).

The Federal Housing Finance Authority (FHFA), which since 2008 has overseen GSEs, in 2020 under the leadership of Trump FHFA appointee Mark Calabria proposed a GSE capital standard rule that requires a capital ratio of 8 percent for GSEs, as well as a minimum leverage ratio of 2.5 percent and additional buffers. Some (like scholars at the Urban Institute) have criticized the FHFA’s original capital plan for being procyclical and for discouraging the use of Credit Risk Transfer (CRT) securities, which shift the risk of borrower defaults on Freddie and Fannie to private investors (fund managers holding CRTs in fact helped shield taxpayers from losses during the COVID-19 pandemic and related financial crisis).

The final rule now published in 2022 (under Biden FHFA appointee Sandra Thompson) requires GSEs to submit annual capital plans that includes prior notice for certain capital actions, estimates of projected revenues, expenses, losses, reserves, and pro forma capital levels under a range of scenarios, and discussion of planned capital actions, how maintain capital commensurate with the business risks and continue to serve the housing market; and expected changes to the GSE’s business plan that are likely to have a material impact on the GSE’s capital adequacy or liquidity. Overall, certainly is major progress on reducing GSE risk-taking.

One pathway to the complete re-privatization of the GSEs is the bipartisan Protecting American Taxpayers and Homeowners Act (PATH), originally introduced by former Rep. Jeb Hensarling (R., Tex.) in 2013. PATH would move to completely eliminate the role of taxpayers in backstopping the secondary housing finance market, by liquidating Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Other, weaker proposals for reform would maintain taxpayer-funded guarantees for GSE mortgages, while ending the existing Treasury net worth sweep of Fannie and Freddie and returning them to private company status and taking them out of federal conservatorship.

Nonetheless, apart from the FHFA capital rule for GSEs, Congress has made little progress has been made on the re-privatization of GSEs. It is essential for policymakers to consider the systemic risk that necessarily follows from placing taxpayers on the hook for real estate defaults.

6. Reexamine the role of the Federal Reserve in creating housing bubbles

Policymakers at the U.S. Federal Reserve have long believed that lowering interest rates is beneficial for the housing market. Reduced interest rates, according to this view, make it easier for low-income Americans to borrow the funds needed to own a home. By increasing demand for mortgages, home prices increase, increasing the wealth of those who already own their homes.

However, over the last decade, home prices have increased substantially in relation to average household after-tax income. The power of low interest rates to increase the incomes of lower- and middle-income households is not clear.

On the other hand, low interest rates dramatically expand the ability of large financial institutions to borrow more money and use it to purchase housing. In 2021, Ryan Dezember of the Wall Street Journal described the phenomenon of “yield-chasing investors…snapping up single-family homes, competing with ordinary Americans and driving up prices.” In 2022, the private-equity firm Blackstone raised $24 billion to invest in real estate, including rental housing.

In response to nine percent inflation, the Fed has signaled that it will continue to gradually raise interest rates from the near-zero levels it has maintained since the pandemic, and more broadly, since the 2008 financial crisis. As they do so, they should examine the role that low interest rates play in decreasing the affordability of housing. There are good reasons to believe that the extraordinary policy interventions of the Fed have made it harder for average Americans to afford a new home.

Expanded Supply + Organic Demand = Affordable Housing

For too long, policymakers have not considered how government-driven restrictions on supply and government-driven expansions of demand have caused housing prices to increase faster than household income. A 21st-century housing agenda should prioritize the opposite goals: phasing out the artificial subsidies for real estate borrowing; increasing the supply of housing; and carefully targeting rental and mortgage assistance to those who most need it.