Executive Summary

Americans are rightfully worried about how to pay for college tuition, which has risen in price far faster than most other consumer goods. In response to rising tuition, federal and state governments have more than doubled the real value of financial aid they provide to public college students. However, the inexorable rise in underlying college costs means that “net” tuition after aid has still gone up. If tuition revenue per student had not increased in real terms since 1996, expansions in financial aid would have reduced the average in-state public college student’s tuition bill to zero.

On a per-student basis, college spending has risen by thousands of dollars over the last two decades. America’s higher education system spends more per student than any other large, developed country. While both instructional and administrative spending contribute to higher costs, administrative spending is rising at a much faster rate. Professors and other instructional staff account for less than half of employees at four-year colleges, and some private research universities have more administrators than professors.

In a well-functioning marketplace, competition weeds out cost inefficiencies and drives prices down. Many factors explain why this has not happened in higher education. Though government subsidies and rising labor costs explain much of the rise in college tuition, they cannot account for all of it. Less-discussed explanations for tuition hikes include significant barriers to entry for new institutions of higher education, as well as a startling lack of price transparency regarding what students will actually pay for college. These factors create an uncompetitive marketplace where tuition can rise unchecked.

To address this problem, policymakers should attack the fundamental causes of tuition growth. While this agenda should include reining in federal financial aid programs, the federal government should also overhaul the accreditation system and increase price transparency, which will encourage more vigorous competition between schools to lower costs. Promoting alternatives to traditional higher education, such as apprenticeships and industry certifications, can also play a role in reducing tuition.

Introduction

A recent Walton Family Foundation survey of young people (ages 13 to 39) found that most are optimistic that they will succeed in life and be able to achieve the American Dream. However, when asked to name the biggest obstacles standing between them and opportunity, survey respondents cited the cost of higher education as the number one barrier. According to the survey, the cost of college outranks health care, the economy, and racial inequality as a perceived problem among Millennials and Generation Z.

In 1989, the average independent young adult under the age of 25 devoted 4.0% of her total expenditures to education, according to the Consumer Expenditure Survey. But as of 2019, that share had nearly doubled to 7.6% of expenditures. Parents are also spending more on their children’s education: two-parent families with children devoted 1.6% of the household budget to education in 1989 but 2.9% in 2019. As the cost of college rises and more people pursue higher education, spending on education is consuming a greater share of the typical family’s budget.

College can be a worthwhile investment for students and their families, even when the costs are considerable. On average, completing a bachelor’s degree is linked to higher earnings, which tend to compensate students for the cost of tuition and time spent out of the labor force. But the rising cost of college threatens to turn a solid investment into a coin flip. Economist Douglas Webber has calculated that the chance college will “pay off” for a particular student declines sharply as the cost of tuition rises.

Moreover, rising expenditures on higher education could act as a drag on the economy as a whole if they do not finance improvements in educational quality. Even as tuition has risen over the past twenty years, the value of a bachelor’s degree has remained stagnant. The wage premium of a college graduate over someone with only a high school degree has remained stuck near 65% for the past two decades. Rising costs and stagnant returns threaten the long-term sustainability of higher education as a pathway into the middle class.

This report examines the rise in college tuition over the past several decades, distinguishing between “sticker price” tuition and the “net price” students pay after financial aid is applied. Even though taxpayers are spending more on aid, net price continues to rise, suggesting that underlying cost growth is the root problem driving price hikes. The report then explores several potential causes of cost growth, including price opacity, barriers to entry, and the perverse inflationary impact of student aid itself. Several policy recommendations to arrest growth in college tuition conclude.

The focus of the analysis will be mainstream four-year colleges at the undergraduate level. For the sake of brevity, the report will ignore graduate schools, for-profit institutions, community colleges, and special-focus institutions like art and music schools. In-state students at public four-year colleges will be the primary focus, since this group tends to dominate America’s undergraduate student population, but private nonprofit four-year schools will also figure into the analysis.

The Covid-19 pandemic is affecting colleges in myriad ways, including lower student enrollment and, in some cases, tighter budgets. As of this writing, comprehensive data on college tuition and finances during the Covid-19 period were not available. We also do not yet know what the higher education sector will look like post-pandemic. The 2018–19 academic year is the most recent period for which good-quality data are available, so the report will focus on the pre-pandemic status quo.

How much have college prices risen?

Most people have heard some variation of the following set of facts. In 1970, tuition at Yale University was a mere $2,550. Today, the school charges an eye-popping $57,700 per year, a figure which rises to $74,900 when including room and board. The implication is that a world-class education that was once affordable with a modest savings account and a part-time job has become out of reach for all but the wealthiest.

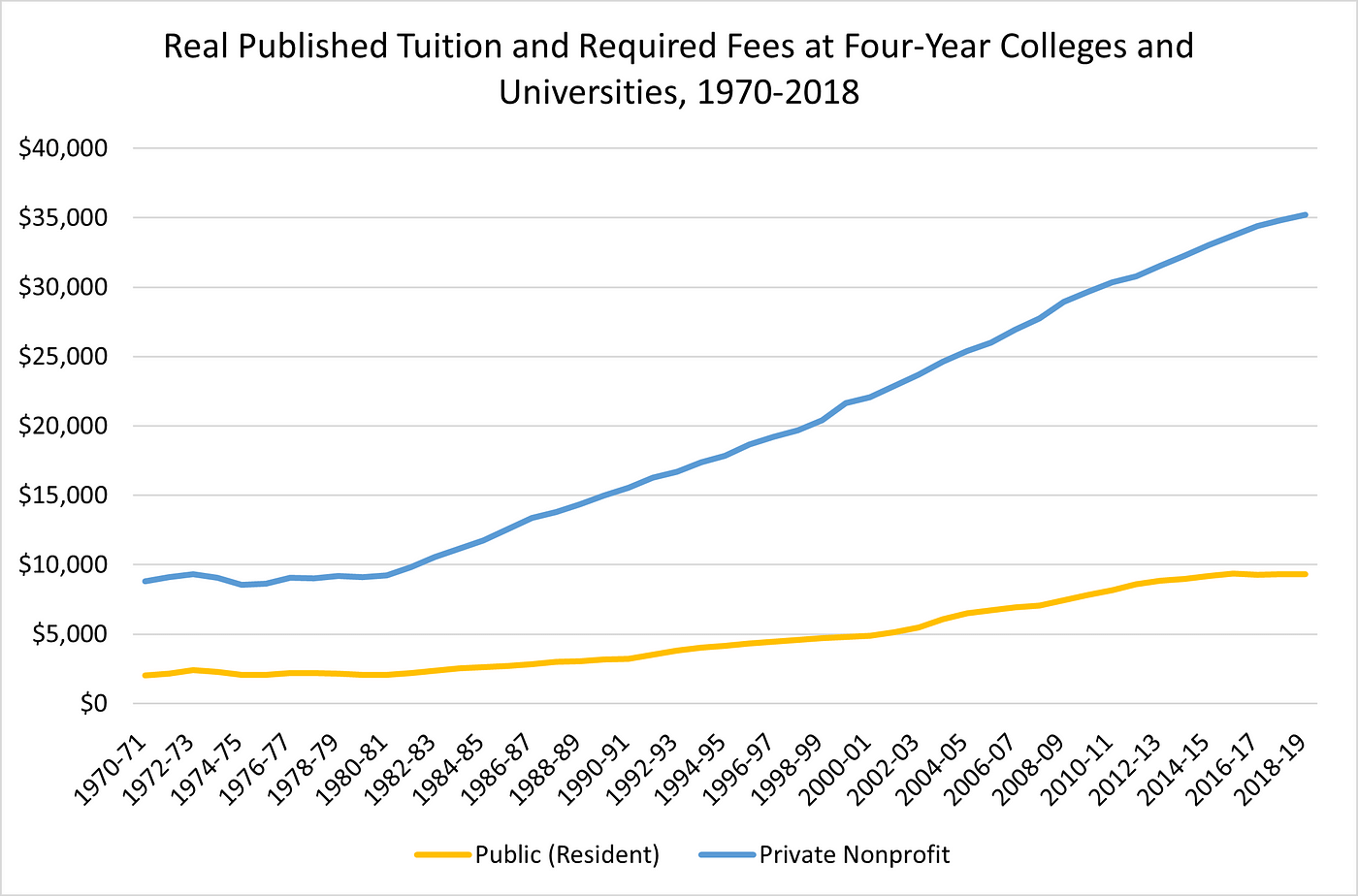

While Yale and its Ivy League peers are outliers, the increase in sticker-price tuition at the average university is still astronomical. At both public and private nonprofit four-year schools, published tuition rates have quintupled in real terms since 1970. The average freshman at a four-year private university now faces a price tag of more than $35,000.

The rise in published prices is misleading, as most students receive financial aid packages that reduce their net tuition payments. The “sticker price” appearing on an institution’s website is an upper bound that usually does not reflect the actual amount students pay. But since sticker price is the most visible measure of tuition at most universities, it is often the figure cited by commentators and politicians and thus shapes the public understanding of college costs. More importantly, it is the first number that students encounter when they research how much a college education will cost them.

Net price, or the amount a student pays after all sources of financial aid are applied, has risen far less than sticker price. Financial aid comes from multiple sources. The institution itself commonly provides a student with internal grants (institutional aid) that reduce sticker price. Institutional aid is more or less an accounting fiction, as it is essentially revenue that the college or university pays to itself. A $2,000 rise in sticker-price tuition accompanied by a $2,000 per-student rise in institutional aid does not change the net tuition revenue that the institution receives.

Other sources of financial aid are external to the institution. The federal government spends $28 billion per year on the Pell Grant, which provides low- and middle-income students with up to $6,495 in aid towards their tuition and living costs. The Pell Grant phases out as a student’s family income rises. While other federal grant programs exist, the Pell Grant is by far the largest and most widely used.

State grant programs, which provide nearly $12 billion in assistance per year, are another significant source of financial aid. Some grant programs, such as New York’s TAP Award and California’s Cal Grant, disburse aid based on financial need. Others, such as Georgia’s HOPE Scholarship, are based on merit and accessible to all students regardless of family income, so long as they earn a minimum GPA or SAT score.

In addition to federal and state grants, students may receive financial aid from other external sources, including income tax credits, veterans’ benefits, private scholarships, and employer tuition benefits. Student loans are not considered aid for the purposes of this analysis, as students are required to pay them back.

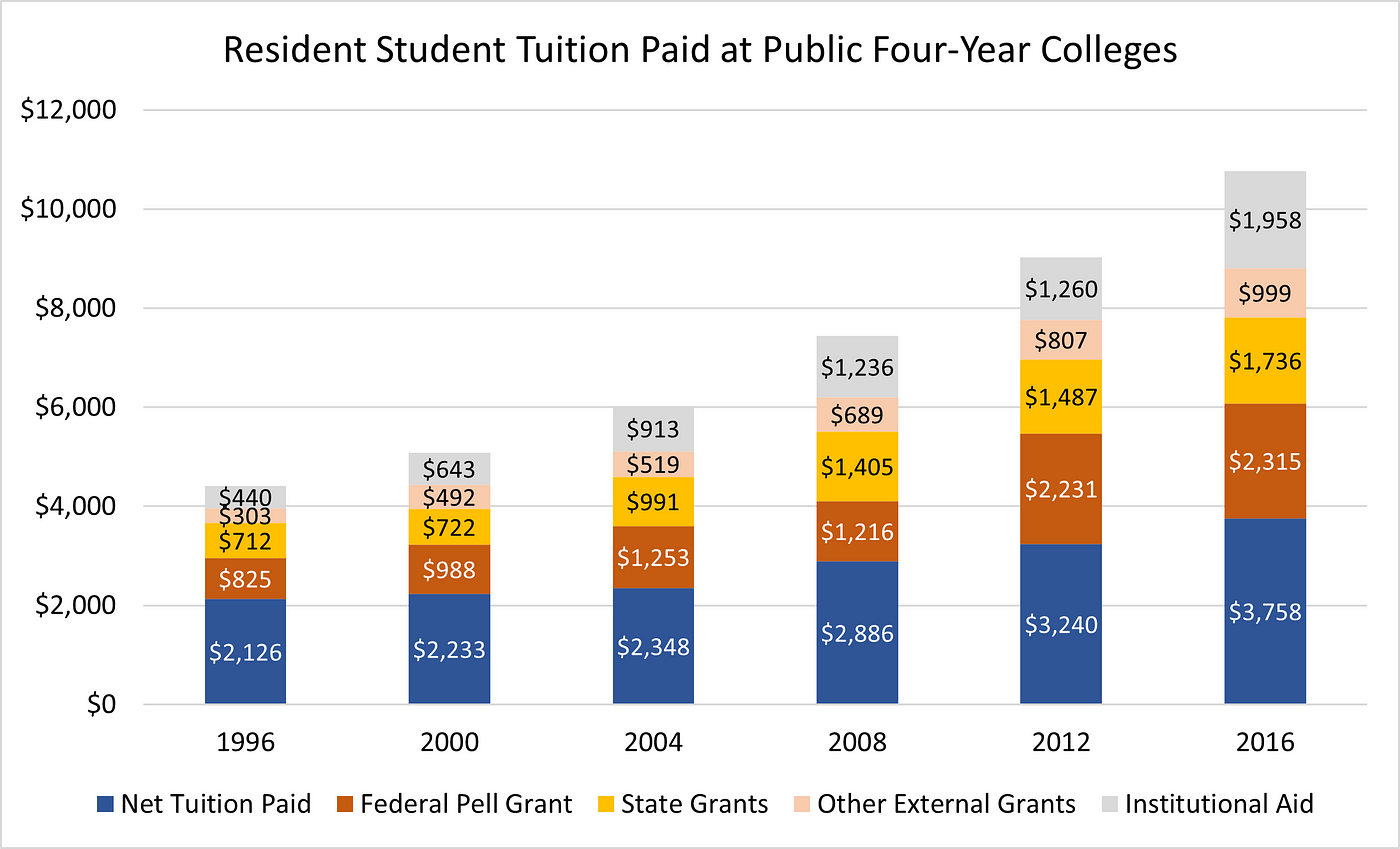

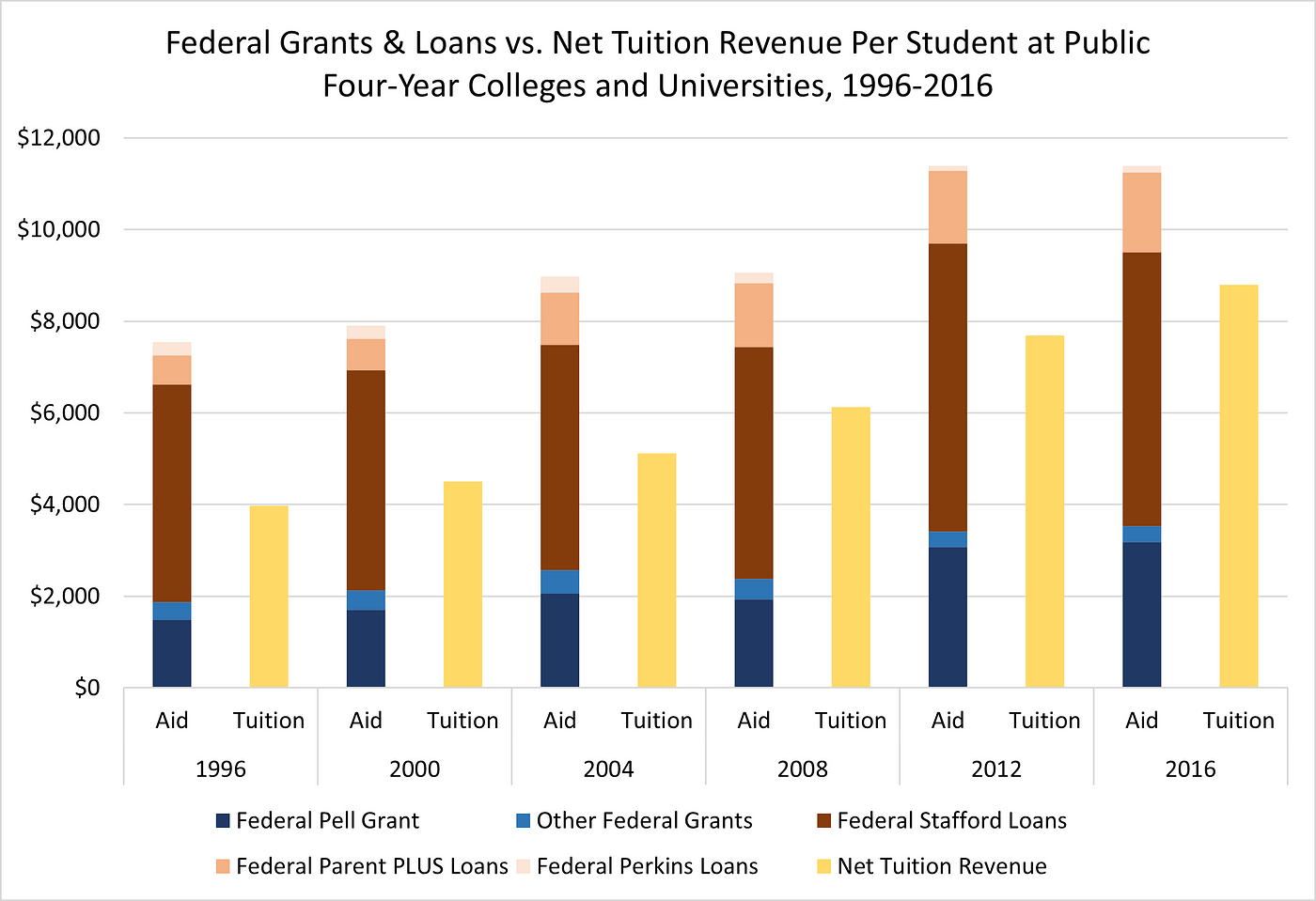

The majority of undergraduate students attend a public institution within their own state, which qualifies them for a significantly lower sticker price than students attending out-of-state or private schools. At the average four-year public university, real sticker price tuition for state residents increased from $4,405 in 1996 to $10,766 in 2016 (144%). Average institutional aid also increased during this time, such that net tuition revenue per student rose slightly less, from $3,965 to $8,808 (122%).

Increases in external grant aid have further slowed the growth in net price for students. For resident students at public universities, the average Pell Grant nearly tripled between 1996 and 2016. Other external grants, including state grants, also rose by a healthy amount. Overall, external aid more than doubled between 1996 and 2016, from $1,846 to $5,050. However, despite this marked increase in generosity, net price after all aid still rose from $2,126 to $3,758 (77%).

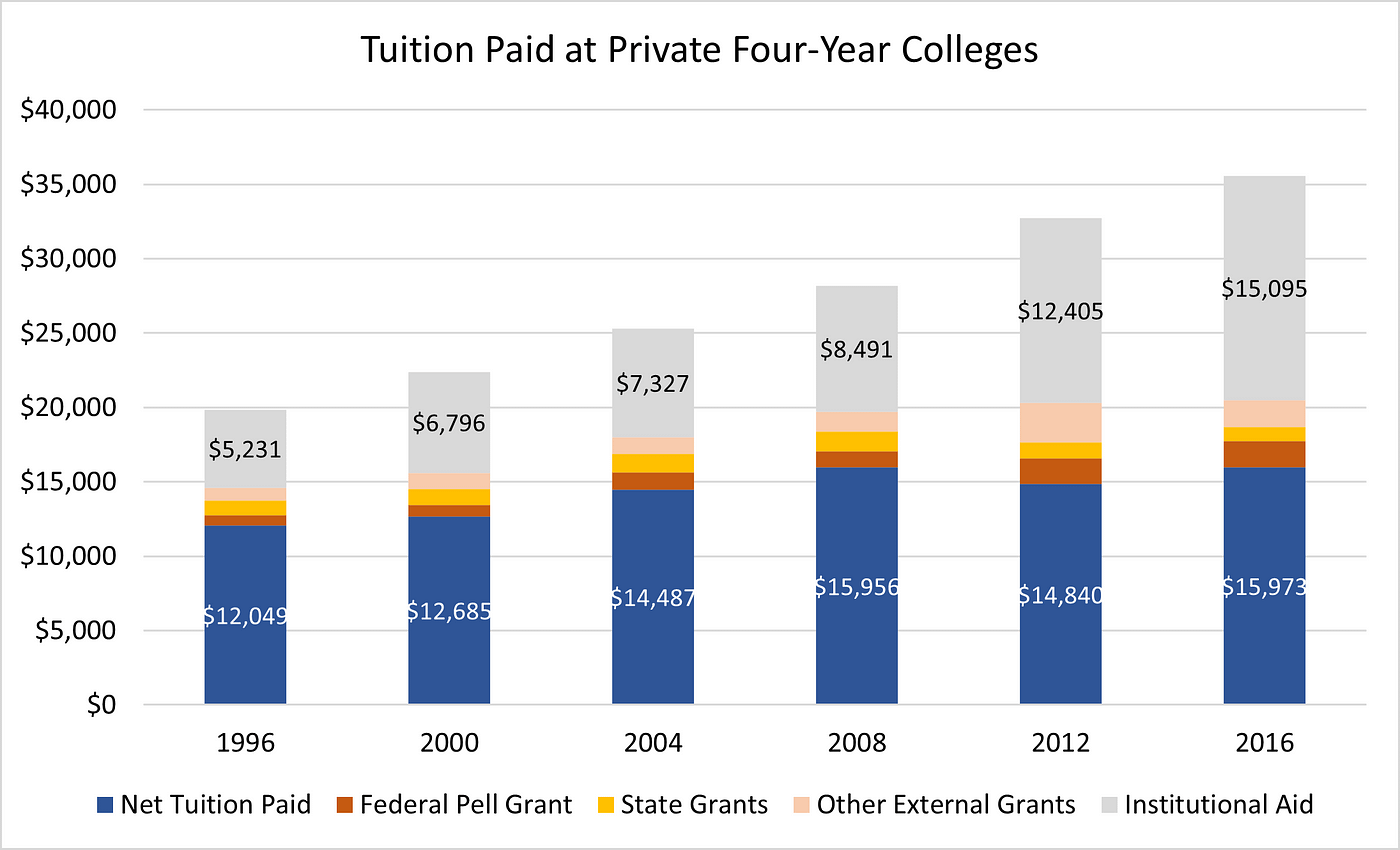

A similar story has played out at private colleges. While sticker-price tuition rose 79% to $35,582 between 1996 and 2016, institutional aid partially compensated for the rise. The average private four-year institution now raises a net $20,487 from each undergraduate student. Students and their families pay most of this directly ($15,973), while external grants contribute the remaining $4,514. Net per-student tuition revenue at private colleges has risen 40% over the past two decades, though it has stabilized somewhat since 2008.

Net tuition revenue at both public and private universities has been on a sharp upward trend since at least 1996. In real terms, public institutions raised $4,843 more from each resident student in 2016 as compared to 1996, while private institutions raised $5,875 more. In both cases, this increase has been less than the rise in sticker price, but it is still a significant change.

The growing generosity of external financial aid has softened the blow for students. Between 1996 and 2016, external grants rose 76% for students at private schools and an astounding 175% for resident students at public institutions. Even so, the net price that students and their families pay after all financial aid, institutional and external, has risen by thousands of dollars in real terms.

Despite far greater taxpayer support for tuition expenses, students are paying more than ever to go to college. To be sure, it is worth considering the counterfactual. Perhaps net prices would be even higher today had Congress and state governments not increased the generosity of financial aid programs.

But we should also consider another counterfactual: what if colleges had not increased tuition in real terms during this period? If net tuition revenue per student had remained at 1996 levels (adjusted for inflation), increases in federal, state, and private financial aid could have reduced the average tuition liability for a resident student at a public university to zero. Lower-income students could have used the more generous federal Pell Grant to defray their living expenses, which are often a significant barrier for students living away from their families for the first time.

Since net tuition keeps rising even as financial aid becomes more generous, the key to understanding rising prices lies on the other side of universities’ financial equation: expenditures. The price of college is high because the cost of college is high. The next section will examine why that is.

What is driving the cost of college?

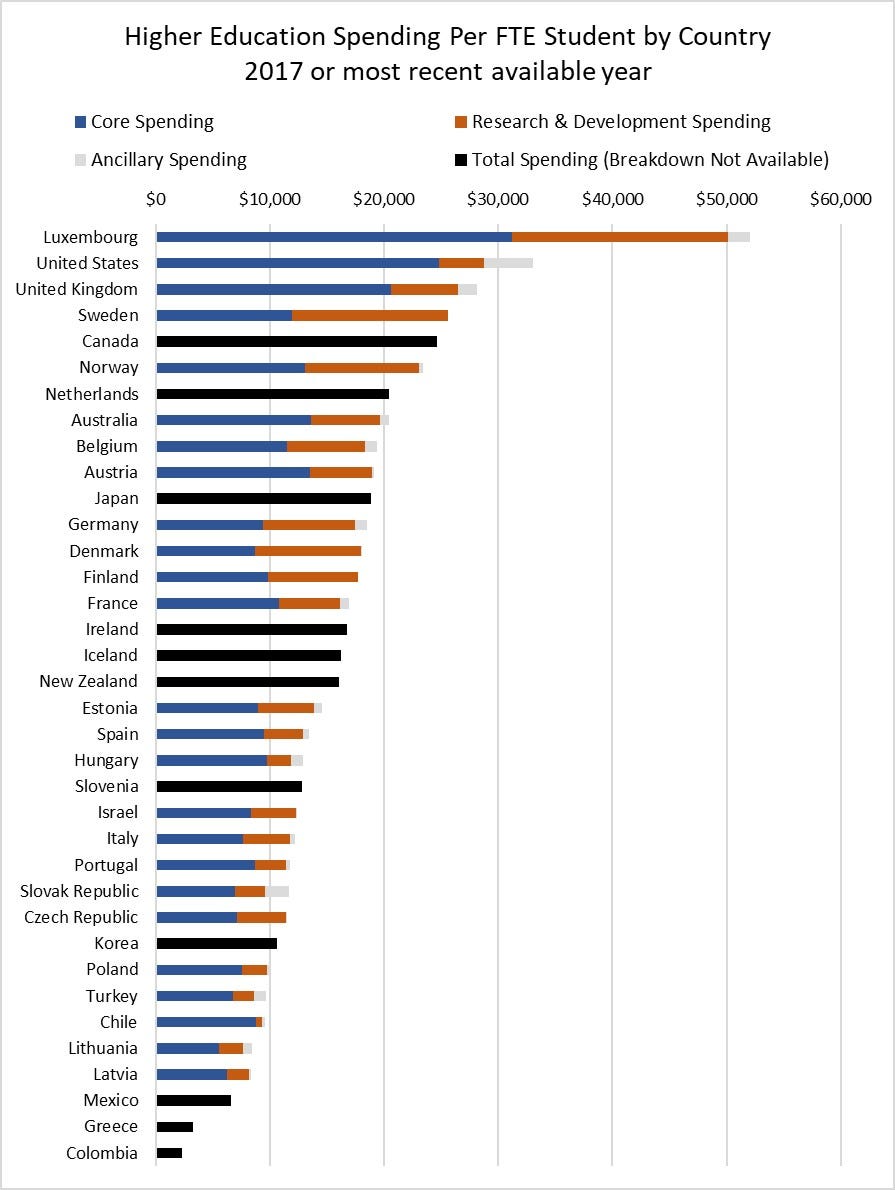

In the United States, spending on higher education outpaces most of the developed world. Combining both government subsidies and private expenditures, the U.S. spends 2.6% of GDP on higher education, almost twice the OECD average of 1.4%. U.S. investment in higher education exceeds peer nations such as Canada (which spends 2.3% of GDP), the United Kingdom (2.0%) and Australia (2.0%).

Altogether, the American higher education system spends just over $33,000 per full-time equivalent student, more than every other OECD nation except Luxembourg. Part of this is driven by America’s residential college experience, with its expensive dormitories and dining halls. These ancillary functions, together with research and development, account for roughly a quarter of higher education expenditures in the United States. However, the U.S. still leads the developed world if we limit the analysis to spending on core university functions such as instruction and administration.

There is no fundamental reason why higher education has to cost as much as it does in the United States; after all, western Europe and the rest of the developed world are able to provide their citizens with education beyond the secondary level for a fraction of the cost.

More detailed cross-national comparisons are not possible with the available data. However, it is possible to more fully examine the breakdown of university spending within the United States, as well as the functions that have contributed most to spending growth over time.

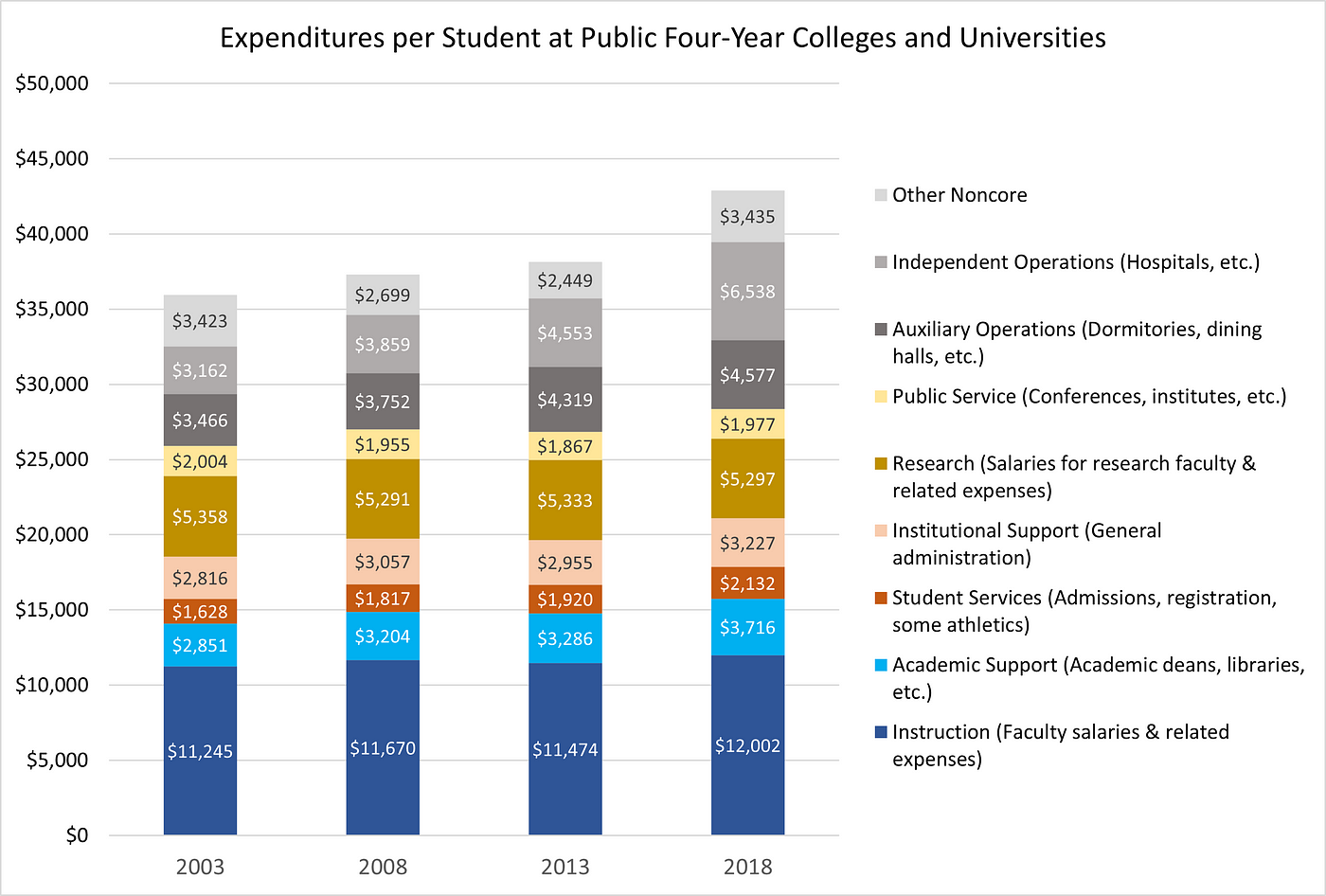

The following figure displays growth in public colleges and universities’ spending by function between 2003 and 2018. Instruction and related spending is in blue, administrative spending is in orange, research and public service spending is in yellow, and various non-core operations such as dormitories, dining halls, and hospitals are in gray.

Instructional expenditures, which include spending on faculty salaries and expenses associated with operating academic departments, constitute the largest single category of core spending at public universities. These schools spend roughly $12,000 per full-time equivalent student on instruction. Per-student instructional expenses increased a modest 7% between 2003 and 2018, but the base level of spending was so high that instruction is responsible for one-third of the increase in core university spending during that time.

In addition to instruction, public universities spend $3,716 per student on academic support expenses. These include some administrative functions like academic deans, as well as libraries and other resources aimed at supporting students in strictly academic pursuits. Though academic support is a relatively small share of overall spending, it is growing extremely fast. Academic support expenditures increased 30% between 2003 and 2018. This accounted for roughly a third of overall spending growth.

Observers commonly blame “administrative bloat” for the rise in higher education spending, and there is evidence for that charge. Spending on non-auxiliary student services, such as admissions and registration, increased 31% between 2003 and 2018. Institutional support, which includes the salaries of high-ranking administrators and other general administrative expenses, rose 15% over the same period. Public institutions spend $5,359 per student on these two administrative categories. Together, they accounted for another third of the increase in core university spending.

Spending on research amounted to $5,297 per student in 2018, while public service expenditures such as conferences, institutes, and radio stations contributed another $1,977. Though these two categories account for a substantial share of institution budgets, they have not grown on a per-student basis since 2003.

Many modern universities are “Christmas trees” that provide a number of non-academic products in addition to the core academic experience. On top of core spending, non-core functions accounted for nearly $15,000 in per-student expenditures in 2018. Non-core enterprises include dormitories, dining halls, self-supporting athletic teams, hospitals, and independent research centers. Though they are a significant share of university budgets, these enterprises are meant to be self-sustaining rather than funded through tuition and fees. However, spending on these non-core functions has risen a remarkable 45% since 2003, meaning they could become a significant financial liability for public colleges if revenue does not meet expectations.

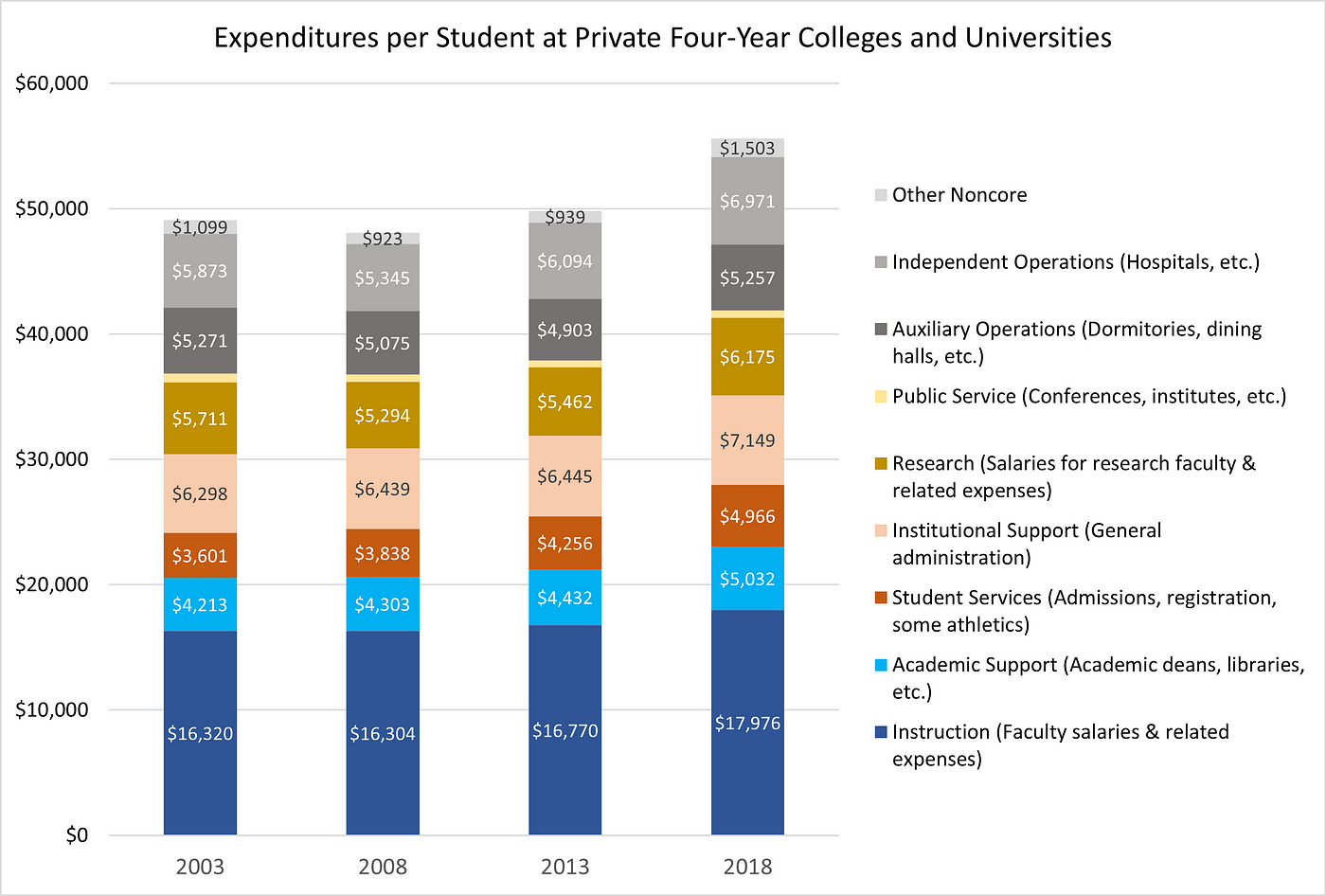

The story is similar at private schools. Core per-student spending at four-year private institutions is 48% higher than at public institutions; the average private college spends $41,887 per student on its core functions. Instruction is once again the largest single category of spending, but academic support and administrative expenses combined are responsible for nearly as much spending as instruction. Notably, private universities’ spending on auxiliary enterprises such as dormitories has not risen on a per-student basis since 2003, and hospital spending has risen only modestly.

Instruction again accounts for roughly one third of the rise in core spending since 2003. Academic support and the two administrative categories represent another 60%, with the remainder due to a modest rise in research spending. Cost inflation overall is a somewhat bigger problem at private universities. Core per-student spending has risen 14% after inflation since 2003, compared to 9% at public institutions.

Institutions self-report their expenditures by function, so the categories of spending shown here are somewhat subjective. Not all expenditures categorized as “instruction” go toward keeping professors on payroll. Moreover, the categories are broad; “academic support” expenditures cover everything from the salaries of college deans to the campus library’s electric bill. Another way to get a sense of where colleges’ expenses come from is the division of staff according to their role at the institution.

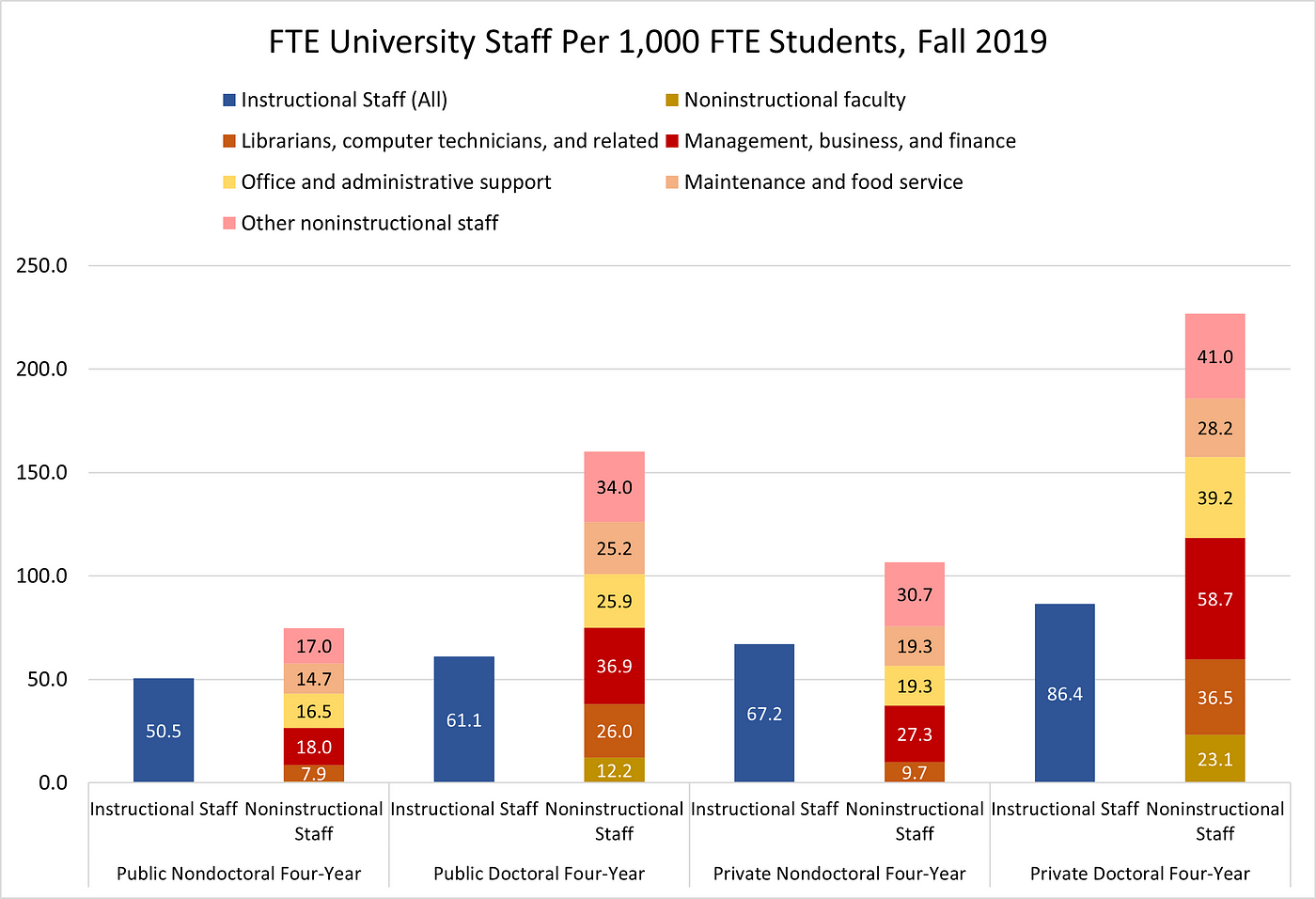

The average four-year college or university has the equivalent of one full-time employee for every five full-time equivalent students. However, less than a third of the average institution’s staff are directly employed teaching students. The exact percentage varies across institution types. At the typical non-doctoral institution, just 40% of FTE employees are instructional staff. At doctoral-granting research universities, only 28% of employees have teaching as a primary responsibility.

While doctoral or research universities have many faculty members engaged in research rather than instruction (indeed, that is the definition of a research university), this does not fully explain the higher number of non-instructional employees at these schools. Doctoral universities also tend to have a larger administrative apparatus. For instance, the average public doctoral university has 62 FTE employees (per 1,000 FTE students) working in “administrative” roles, including management, business, and office and administrative support. In fact, these schools have more FTE employees working as administrators than working as instructional staff.

At private doctoral universities, generally the most expensive class of institution in the United States, the ratio is even more skewed. These schools have 86 FTE instructional staff and 227 non-instructional staff per 1,000 FTE students. About 20% of institution staff are employed in management or business roles, another 13% are office or administrative support workers, and 12% work as librarians, museum staff, or computer technicians. Only 28% are instructional staff.

While comparing trends in staffing over time is difficult due to data limitations, Robert Kelchen of Seton Hall University documents a modest rise in the number of higher-level administrators at research universities and a substantial rise in the number of lower-level administrators at all institutions between 1990 and 2012. The number of full-time faculty has stayed mostly flat, while the number of part-time faculty has risen.

To be sure, not all non-instructional employees put upward pressure on tuition. Some of these employees are associated with self-funding auxiliary enterprises or independent operations. Still, the fact that just 31% of FTE employees at four-year universities are employed teaching students should give pause to anyone concerned about financial discipline in higher education.

Since 2003, only one-third of the increase in colleges’ and universities’ core expenditures has gone to spending on instruction. Almost all the rest has fed the growth of the vast administrative apparatus of these institutions. This is especially true at research universities, where people working in administrative roles often outnumber professors. While some administrative spending will always be necessary, it’s hard to escape the impression that things have gotten out of control.

Now that we know where universities’ cost pressures are coming from, the next question is why they have persisted for so long. Market economies tend to weed out unproductive spending as new providers of a good or service discover efficiencies and drive down prices. But in higher education, the exact opposite has happened.

Why haven’t market pressures reduced the cost of college?

Over the past 20 years, annual consumer price inflation has averaged a humdrum 2%. But in what many commentators have called the “Chart of the Century,” economist Mark Perry reveals that the unassuming average masks substantial variation across sectors. The prices of hospital services, child care, and education have risen well in excess of average inflation, and have also outpaced the growth in hourly wages. The Financial Times calculates that 88% of consumer price inflation since 1990 is down to just four sectors: health care services, prescription drugs, housing, and education.

But as Perry shows, many other goods and services have fallen in price over the same period, including computers, televisions, and cell phone services. The first laptop computer debuted in 1981 with a price tag exceeding $5,000 in today’s dollars. Since then, the price of computing power has dropped by several orders of magnitude. History supplies many examples of once-expensive products becoming astronomically cheaper when innovation and competition work their magic. But the cost of college remains stubbornly high, and rising. Why?

Observers have proposed several hypotheses as to why the cost of college keeps increasing, especially in comparison to other goods and services. Let us examine each of these hypotheses in turn, going from the least compelling to the most.

State disinvestment

The state disinvestment hypothesis posits that tuition is rising because state and local governments have reduced the direct appropriations they provide to colleges and universities on a per-student basis. Starved for revenue, institutions must instead raise tuition to continue their operations.

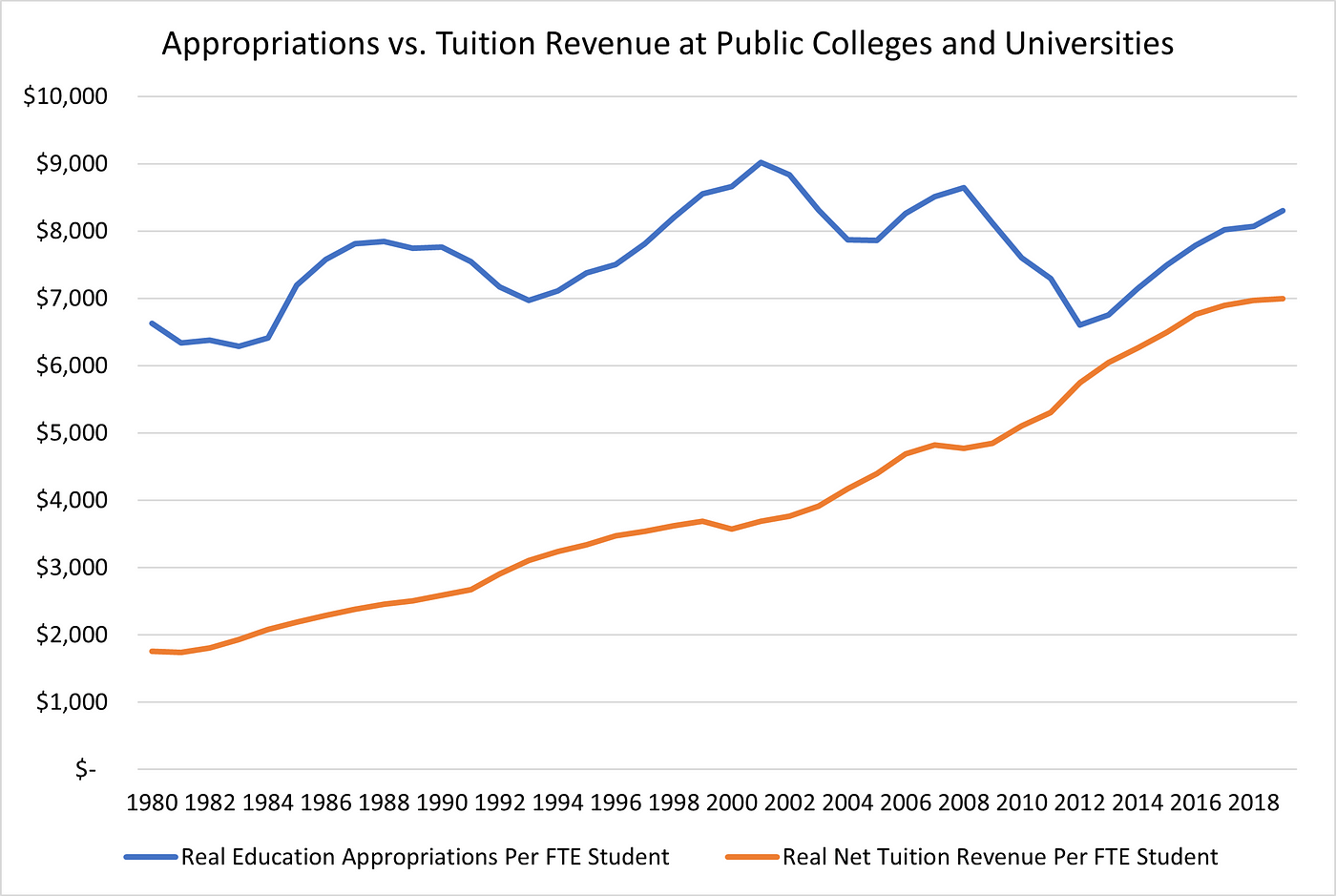

As a blanket explanation for the rising cost of college, state disinvestment is unsatisfactory. The simplest reason is that real per-student appropriations for public colleges and universities have risen $1,700 in real terms since 1980.

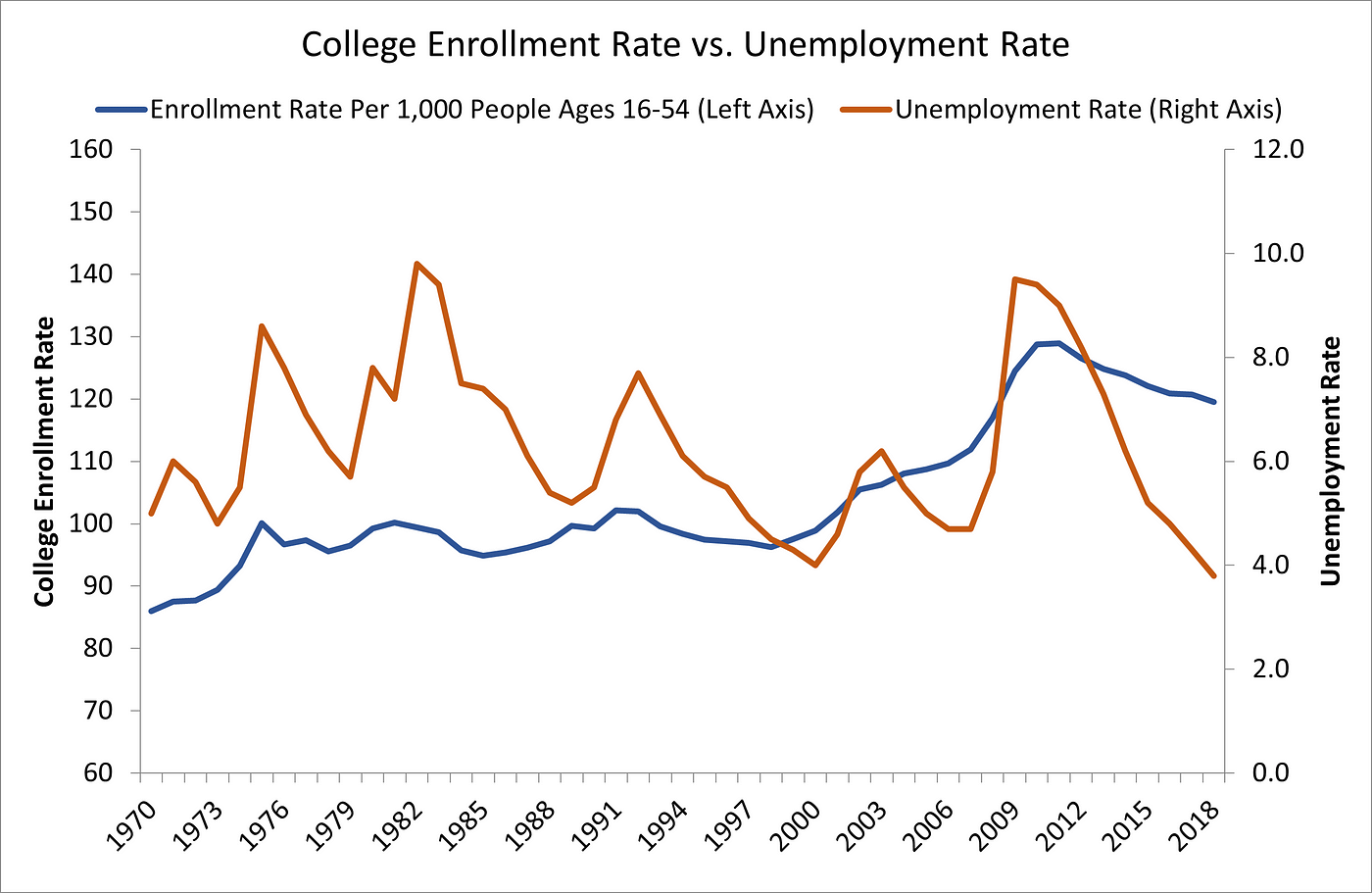

State funding for higher education is highly procyclical. Appropriations tend to contract during recessions and expand during booms, in line with the macroeconomic pressures on state budgets. Since college enrollment does the opposite, rising during recessions and falling during booms, swings in per-student appropriations are even more extreme. Dramatic reductions in per-student funding during recessions, accompanied by rises in tuition, feed the impression that tuition hikes are due to state budget cuts.

If falling appropriations were the explanation for rising tuition, we would expect public universities’ per-student tuition revenues to be highly countercyclical. But that is not empirically true. Consider a recent example. From 2007 to 2012, per-student appropriations fell $1,900 in real terms, while per-student tuition revenue increased by $900. But over the next five years, from 2012 to 2017, per-student appropriations rose $1,400, while per-student tuition revenue still climbed by $1,100. In other words, tuition tends to rise at a fairly constant clip regardless of what happens to state appropriations. Andrew Gillen of the Texas Public Policy Foundation calculates that only a small portion of changes in state funding are “passed through” into changes in tuition, while “the vast majority of the typical year’s increase in tuition is unrelated to changes in state funding.”

Baumol’s cost disease

In 1965, economist William Baumol introduced the world to the economic phenomenon that would come to bear his name: Baumol’s cost disease. According to his theory, the productivity of labor rises faster in some industries than others. While improvements in technology make it possible to produce a car with fewer man-hours, such productivity gains are much harder to secure in other, less productive industries. But rising wages across the economy will tend to put upward pressure on wages in the low-productivity industries. With no way to economize on labor, those industries have no choice but to accept higher costs.

Baumol himself thought that higher education was the perfect example of cost disease in action. He wrote in 1967: “The relatively constant productivity of college teaching…suggests that, as productivity in the remainder of the economy continues to increase, costs of running the educational organizations will mount correspondingly, so that whatever the magnitude of the funds they need today, we can be reasonably certain that they will require more tomorrow, and even more on the day after that.” Constant class sizes and rising professor salaries lead to unavoidable increases in costs.

Roughly one-third of college cost growth comes from instructional expenditures, and Baumol’s cost disease may explain this aspect of rising expenditures. An in-depth examination of cost trends by economists Robert Martin and Carter Hill concludes that “Baumol effects” account for between 23% and 32% of overall increases in costs at public research universities between 1987 and 2011. But that also means that the overwhelming majority of cost increases in higher education are not due to Baumol’s cost disease.

Instead of rising professor salaries, much more of the increase in higher education costs has come about because universities are hiring different sorts of employees. “From 1987 to 2011,” Martin and Hill write, “the number of full time non-academic professional staff per tenure track faculty member doubled at public universities and increased by 47 percent at private universities.” Recall that today, instructional staff are a minority of FTE university employees. Baumol’s cost disease is a much weaker explanation for the growth of the university administrative apparatus.

Moreover, we should question the assumption that substantial labor productivity gains in higher education are impossible. Outside of traditional higher education, innovation in the business of learning is widespread. Lower-cost products such as coding bootcamps and massive open online courses have entered the stage in recent years. Though productivity-enhancing innovation has not yet found its way into traditional colleges, that could be because universities have not faced the competitive pressures necessary to kickstart productivity growth. Blaming Baumol’s cost disease for rising tuition begs the question.

The Bennett Hypothesis

In 1987, Secretary of Education William Bennett popularized the idea that federal grants and loans to college students facilitate increases in college tuition rates. In a New York Times op-ed, Bennett wrote that “increases in financial aid in recent years have enabled colleges and universities blithely to raise their tuitions, confident that Federal loan subsidies would help cushion the increase.” The theory that colleges are able to raise tuition at a faster rate when federal financial aid programs are more generous is now colloquially known as the Bennett Hypothesis.

The Bennett Hypothesis is intuitive as a matter of economics. Government subsidy of college tuition reduces the price sensitivity of students and their parents, enabling cost increases by universities. Moreover, a nonprofit organization like a college has less incentive to minimize costs as a profit-maximizing firm does, according to a theory advanced by economist Howard Bowen. Instead, institutions adjust their costs to match whatever revenues they are able to raise. When available revenue streams expand, perhaps because of an increase in federal student aid, colleges will increase their expenditures rather than passing the new subsidy on to students.

The Bennett Hypothesis has received considerable analytical attention from economists. In a meta-analysis of 25 empirical studies, Jenna Robinson of the James G. Martin Center concludes that the majority of research shows some positive connection between increases in federal student aid and subsequent increases in tuition (though a handful of studies find no effect). A team of researchers led by David Lucca of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York finds that a $1 increase in federal subsidized loan limits generates a 60 cent increase in published tuition, with larger effects for selective private institutions. Lesley Turner of Vanderbilt University concludes that colleges “capture” a portion of increases in the federal Pell Grant by reducing the institutional grants they provide students, a phenomenon which is again more prominent at selective private schools. Another study finds that the Parent PLUS program, which provides effectively unlimited federal loans to parents of undergraduates to help pay for college, has an inflationary impact on tuition.

The general conclusion from the literature is that colleges and universities either raise tuition or cut back on institutional aid to capture some, but not all, of the grant and loan aid that the federal government makes available to students. Selective private schools, which are already the most expensive class of institution, seem to capture a greater percentage of available aid than other schools. Moreover, it is likely that the sheer volume of federal aid ($150 billion in 2018–19) creates a general expectation among colleges that the federal government will regularly increase aid to meet their revenue demands.

However, the Bennett Hypothesis cannot explain all of the increase in college tuition. For starters, federal undergraduate loan limits have been frozen in nominal terms since 2008, meaning loan limits have declined in real terms. Yet tuition at public colleges and universities has continued to climb at a steady rate. Between 2012 and 2016 at public colleges, aid disbursed through federal Title IV programs (including Pell Grants, other federal grants such as work-study, and federal student loans) did not increase at all for the average student, while net tuition revenue increased by over $1,100. In other words, the tuition rise during this period is not fully explained by changes in federal aid.

Secretary Bennett clarified in his New York Times op-ed that “federal student aid policies do not cause college price inflation, but there is little doubt that they help make it possible.” Past increases in college tuition would have been less dramatic had the federal government constrained the availability of grants and subsidized loans. But it is a mistake to call the Bennett Hypothesis the sole explanation for tuition hikes. Even Bennett himself did not take the argument that far. Title IV aid is an enabler of tuition increases, but it is not the only one.

Barriers to entry

According to economic theory, prices may be inefficiently high if markets are not contestable. If new providers of education cannot enter the market and compete with existing colleges and universities, then the incumbent institutions do not face pressure to lower their own prices or even seek out cost efficiencies. As a result, college tuition may climb even as prices in more competitive markets fall.

The idea of colleges and universities as a non-contestable market may seem odd. There are so many colleges in America that ranking them is a cottage industry. But most of those colleges are not available to the average student. As Beth Akers of the Manhattan Institute writes: “While more than 6,000 colleges and universities in the country have accreditation and eligibility for federal student aid programs, the set of choices for most students is far more constrained. For most, markets for higher education are exceedingly local. Most students don’t pick up and move their lives across the country to enroll in college.”

Forty-two percent of first-year students in bachelor’s degree programs attend a school within 50 miles of their home, and 18% plan to live with their parents while studying. The ability to save money while living with parents or relatives is a powerful financial incentive for students to remain close to home. In addition, public institutions offer steep discounts for in-state students, which also limits the number of options for the financially conscious. Local colleges and universities may hold a special appeal to students, perhaps because they know people who attended the school or idolize its sports teams. For these reasons and others, roughly two in five high school seniors apply to just one college or university.

The localized nature of the higher education marketplace puts upward pressure on tuition. But there are also artificial barriers to entry. New institutions of higher education generally must receive approval from state authorizing agencies before they can operate. The requirements imposed on institutions newly seeking authorization can be burdensome and time-consuming. An American Enterprise Institute report by Andrew Kelly, Kevin James, and Rooney Columbus found that the process of authorization can take up to a year or more to complete. Requirements for authorization can range from a minimum size for physical classrooms to a “pleasant and inviting atmosphere” in the campus library. Some authorizing agencies, such as California’s Bureau for Private Postsecondary Education, take a hostile attitude toward educational innovations like income-share agreements, which can derail new institutions based around these models.

In order to get access to federal student aid programs, including Pell Grants and student loans, institutions must also receive recognition from an accreditor. Though it’s possible to run a successful college without access to federal aid, institutions which choose this route are operating on a tilted playing field relative to incumbents. Accreditation from a recognized agency is usually necessary to effectively compete. But gaining accreditation is a Herculean task, which can take two years or more and involves several thousands of dollars in fees.

Moreover, most accreditors have an incentive to limit the number of new schools they authorize. That is because accreditation commissions, which make final decisions on whether to accredit a new school, are mostly composed of representatives from schools already accredited by that agency. As of 2016, two-thirds of accreditation commissioners were employed by a school already recognized by that accreditor. One-third were college presidents. Since many accreditors have an effective monopoly on accreditation within certain regions of the country, it is hard for schools to secure recognition from an accreditor outside their home region. Essentially, new institutions must seek approval from the incumbent colleges they intend to disrupt.

To be sure, protecting students from unscrupulous institutions and diploma mills is an important function of state authorizing agencies and accreditors. But they also represent barriers to entry that new institutions must leap in order to compete down tuition. Designing policies to protect students without unduly inhibiting competition is a critical task for policymakers going forward.

Price opacity

A central element of market competition is consumers’ ability to comparison-shop. A consumer looking to buy a laptop computer can easily look up the prices and capabilities of many different models and balance superior quality against higher cost. Comparison-shopping disciplines the market and holds prices to a reasonable level.

In higher education, comparison shopping is far more difficult. Colleges only publicly advertise their sticker prices, which are usually outrageous and unreflective of reality. Though the average student receives considerable financial aid from both institutions and external sources, it is difficult for students to know how much aid they will get, and therefore the net price they will pay, before they are accepted to college.

This pricing structure constrains students’ ability to comparison-shop. The typical student applies to just two or three colleges, and the most common number is one. Moreover, college admission rates are falling at most four-year schools, so the average student will be accepted at even fewer institutions than she applies to. When all is said and done, a student may only have one or two options among which she can compare net prices.

Beth Akers sums up this phenomenon’s effect on competitive pressures: “The result of this pricing process is that aspiring students must make decisions about if and where to enroll based on a limited set of information about the options available to them. This lack of transparency limits the extent to which competition among institutions can put downward pressure on prices.”

Colleges take advantage of students’ limited choices to squeeze every penny out of students and their families. Most four-year schools hire “enrollment managers” who individually estimate the highest price each accepted student is willing to pay and calibrate financial aid offers accordingly. This makes net tuition virtually impossible to predict with certainty ahead of time.

Even when they get their financial aid award letters after being accepted to college, students may have a hard time understanding what they must actually pay. An analysis of 11,000 award letters by New America reveals that 70% do not clearly distinguish between grants and loans. Often, loans are misleadingly marketed as “awards.” Not coincidentally, a Brookings Institution report finds that almost half of current college students underestimate the amount of debt they have by over 20%. Fourteen percent of student borrowers mistakenly believed they did not have student debt at all.

What’s more, only 40% of award letters clearly indicate the net price students are liable for after aid, according to New America. Some count loans as aid and misleadingly print a bottom-line net price that appears far lower than it really is. Confusing award letters cause students to seriously underestimate how much they are actually paying for college, which in turn makes it easier for colleges to charge higher net prices.

Once students matriculate at a particular college, they are captive consumers. Many colleges engage in “bait-and-switch” practices that increase net price after the first year. As Stephen Burd and Rachel Fishman write, “about half of all colleges front-load grants and scholarships so that students receive a bigger discount their first couple of years but then face a financial aid package filled with loans in subsequent years.” Financial aid expert Mark Kantrowitz calculates that colleges slash institutional grants for returning students by an average of $1,400, compared to first-years.

A lack of price transparency bedevils many sectors of the economy that have seen the most rampant price inflation, including education and health care. It’s difficult to imagine getting the cost of higher education under control without tackling the opacity of the college pricing system.

Credential inflation

Eighty-seven percent of adults consider a college education either “very important” or “fairly important,” according to Gallup. Though public confidence in the higher education system has slipped in recent years, most people still see college as the best, if not the only, pathway to the middle class.

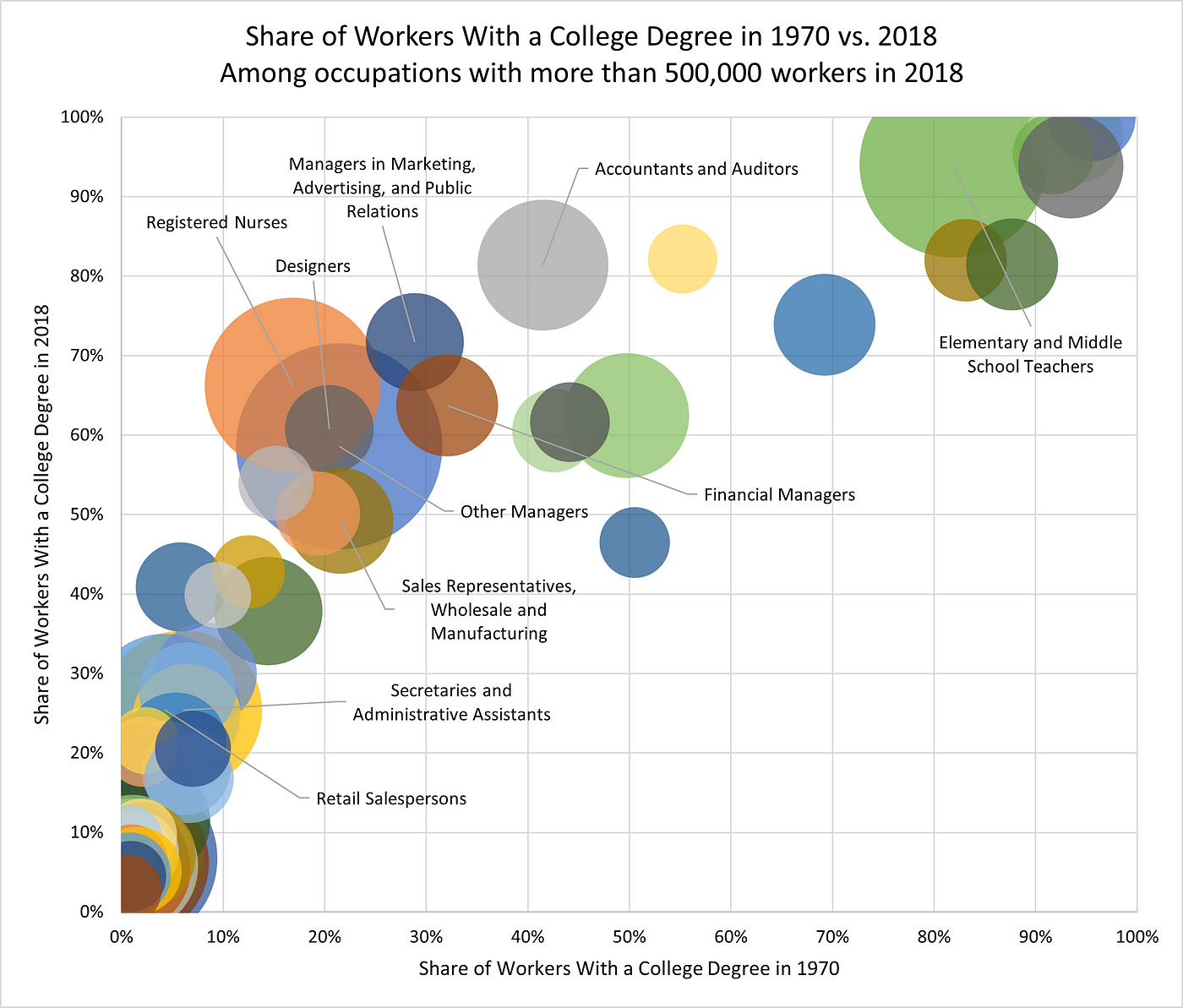

There’s some truth to this perception. A college degree has become a de facto requirement for many middle-income jobs, even those in which a degree was previously not the norm. For instance, just 42% of accountants and auditors in 1970 had a college degree, but today the figure is 81%. It’s becoming more common for secretaries and retail sales workers to have bachelor’s degrees, and college has become almost universal among schoolteachers and pharmacists.

While the skills required for some of these jobs have undoubtedly changed, that is not universally true. An analysis by Joseph Fuller and Manjari Raman reveals that millions of job postings ask applicants to have a bachelor’s degree even though a majority of people currently working in those jobs do not have a degree. Employers sometimes include a bachelor’s degree requirement on job postings as a way to filter for applicants perceived as better-qualified, not because a college education confers the skills required to do those jobs. When this happens on a large scale, we call it credential inflation.

Credential inflation can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. Empirical research finds that the number of job postings requiring a bachelor’s degree tends to rise during recessions, when weak labor markets allow employers to become more choosy about job applicants. Over half of employers who raised educational requirements for job postings did so because there were more college graduates available, according to a Northeastern University survey.

Also due to the weak labor market, college enrollment surges during downturns, since workers see education as a better option than unemployment. The share of job postings requiring degrees then remains at an elevated level even as the labor market returns to normal, because employers can find more educated workers than before.

This phenomenon shuts less-educated workers out of good middle-income jobs and generates a perception among young people that you need a college degree to succeed in life. Since college appears to be the only pathway to the middle class, students’ willingness to pay for education rises (though not their willingness to pay happily). So long as colleges see themselves as the sole gatekeepers to middle-income jobs, they will continue to exploit that power by raising prices.

Lowering barriers to entry, increasing price transparency, and imposing sense onto federal financial aid programs will all help reduce the cost of college for students. But sometimes, for truly transformational change to happen, industries must be disrupted from the outside. The price of indoor lighting did not plummet because someone invented a longer-burning candle, but because Thomas Edison invented the lightbulb. It’s important to remember that when students pay for college, they aren’t really buying an education; they’re buying access to a better future. In order to secure a transformational change in the cost of a better future, perhaps traditional higher education needs to be disrupted by something else entirely.

How to fix the cost of college

It’s impossible to pin cost inflation in higher education on any one culprit, because many aspects of the higher education system contribute to tuition growth. Policy measures to remedy the rising cost of college should therefore attack each of the guilty factors individually. The recommendations of this report fall into four categories defined by four of the principal causes of tuition inflation: rationalizing federal aid policy, lowering barriers to entry, improving price transparency, and creating conditions conducive to disruption.

Increases in federal grant and loan aid can only explain part of the rise in college tuition. However, the portion of tuition inflation attributable to aid is a lever over which policymakers have a great deal of control, at least relative to other causes of tuition inflation such as Baumol’s cost disease. Congress should take the following steps to rationalize the nation’s federal student aid infrastructure with the aim of constraining tuition growth:

- Eliminate exploitative Parent PLUS loans. The Parent PLUS loan program allows parents of undergraduates to borrow effectively unlimited sums to pay for their children’s education. Scholars have identified a causal link between Parent PLUS availability and tuition hikes. Moreover, Parent PLUS loans carry higher interest rates and lack many of the consumer protections given to other federal loans. However, less than 10% of undergraduates were dependent on Parent PLUS loans as of 2016, and most of those were at expensive schools. Eliminating Parent PLUS for new borrowers would therefore constrain future tuition growth but entail only minor immediate disruption to higher education.

- Penalize schools where graduates’ earnings are low relative to the debt they take on. Student debt can be a useful tool to finance higher education. But policymakers should take steps to ensure that taxpayer-backed debt only flows to institutions and programs where value justifies cost. One way to do this is a debt-to-earnings test: schools at which the ratio of average student debt to graduates’ earnings exceeds a certain level should face a prorated penalty. The penalties will give schools a strong financial incentive to lower debt-to-earnings ratios by either cutting prices or increasing the value of the education they provide. This policy doesn’t rule out price increases, but they must be justified by commensurate improvements in education quality.

- Tie increases in government subsidies to consumer price inflation. Student loan limits do not automatically adjust each year, but rise on a discretionary basis when enough pressure builds on Congress to increase limits. The Pell Grant generally keeps pace with inflation from year to year, but occasionally rises in large “jumps” when Congress decides to increase college aid. Instead of increasing aid in a discontinuous, haphazard fashion, Congress should simply tie grant and loan levels to overall consumer price inflation. This policy will make aid predictable, but avoid rewarding colleges who allow their costs to increase in excess of inflation.

Lowering barriers to entry is trickier than rationalizing student aid, since barriers to entry often have the reasonable purpose of protecting students from unscrupulous institutions. Still, many of the barriers that currently exist do little to improve the quality of education, while protecting incumbent colleges from competition. States and the federal government can remove many of the unnecessary barriers that keep competitors out and prices high:

- Restructure accountability policy around education outcomes, not inputs. Gatekeepers of the higher education marketplace, including accreditors and state authorizers, require new postsecondary institutions to demonstrate that they are using specific inputs in the education process, such as a certain curriculum type or a minimum teacher-student ratio. Policymakers should care about outcomes such as graduate earnings and job placement rates instead, since students cite those outcomes as their primary reason for attending college. If an institution achieves a certain outcome, gatekeepers should be agnostic as to the pedagogical or business strategy it uses to get there. Requirements based around education inputs should be significantly scaled back.

- Remove accreditors as gatekeepers of federal student aid. The accreditation model was never meant to be a gatekeeper for hundreds of billions of dollars in taxpayer money, because accreditation agencies long predate federal Title IV aid. Accreditation began as a voluntary system by which colleges and universities held one another accountable, but it has morphed into a financial necessity for most institutions because of its gatekeeper role. The conflicts of interest in the accreditation system are inherent. The Department of Education, in consultation with state authorizers, should set its own standards for approving new institutions to participate in Title IV aid programs, and relegate accreditors to the purely private role they held prior to the creation of Title IV.

- Allow provisional approval while new institutions demonstrate outcomes. Unlike inputs, outcomes of education cannot be measured before an institution has had a chance to operate. State authorizers should therefore grant new institutions provisional approval for several years while they demonstrate their value. Federal student aid can also employ a provisional approval model for new institutions. Beth Akers recommends “[using] deferred compensation to colleges so that they do not receive funds until they have proven job placement, earnings, and financial solvency among their graduates. Schools with a promising business model would be able to borrow against this future stream of income in private financial markets to fund their initial operations.”

Markets need price transparency to function well. However, that attribute is fundamentally lacking in higher education, thanks to a bewildering array of institutional and external grant programs. Fortunately, there are several straightforward policy options available to improve price transparency.

- Standardize financial aid award letters. As a team of scholars at New America document, colleges usually do not provide clear information to students regarding the aid they receive and the net price they are responsible for. Any institution that receives federal Title IV funding should be required to inform students of their aid package in a clear and standardized fashion. Student loans should be clearly distinguished from grant aid. Policymakers should expect colleges, which handle federally originated grants and loans, to be at least as transparent as regulators require banks to be with privately originated mortgages. To that end, award letters should also include estimated monthly payments on federal loans.

- Collect and release better net price data. While tools exist to help students estimate net price, these have frequently proven inaccurate because they are based on old and incomplete data. Fortunately, releasing better data on net price at federally-funded colleges is a bipartisan priority. Congress should repeal the federal ban on a student-unit record data system, which would allow much more precise estimates of net price. As it happens, most of the data required to produce these estimates is already collected by various administrative agencies; the challenge is organizing and releasing it. Giving students a reasonable estimate of net price before they even apply to college will make it more difficult for institutions to gouge captive students once they are admitted.

- Pilot “all-in” upfront pricing. Carlo Salerno of CampusLogic proposes a more significant overhaul of college pricing. Rather than offering students an estimate of their net price at the beginning of each academic year, colleges could disclose an “all-in” binding price for all four years upfront. This makes it impossible for colleges to surprise upperclassmen with cuts in grant aid, and also gives students a better sense of the overall costs they will incur at the start of their college careers. However, there could be unintended consequences associated with such a major change to pricing practices, so this and other innovative ideas should be piloted before becoming a part of standard higher education policy.

All of the above recommendations will put downward pressure on the price of college, but are unlikely to reduce it by orders of magnitude. Truly transformational change in the cost of access to a better future will require disruption of the traditional higher education model. While policymakers cannot generate disruption by decree, there are ways to create conditions more conducive to disruption in higher education.

- Expand alternatives to college such as apprenticeships. The United States lags well behind other rich countries in developing its apprenticeship sector. According to Robert Lerman, apprentices constitute just 0.2% of the U.S labor force, compared to almost 4% in Germany. The few apprenticeships that do exist in the U.S. have posted impressive results, and research suggests the model is ready for expansion. But the playing field is not level between traditional higher education and the alternatives, since colleges and universities get tens of thousands of dollars per student in direct appropriations and subsidized student aid. The federal government could help address this imbalance by creating a program to top-up apprentices’ wages while they are in training. Another idea is to allow Pell Grants to be used for any classroom components to an approved apprenticeship, as Lerman and Tamar Jacoby suggest.

- Support competency-based assessments of learning. It makes no sense for students to pay for college classes to learn material that they have already learned elsewhere, or could learn somewhere outside the college classroom. Many colleges accept AP, IB, or CLEP exam scores for credit; governments should encourage schools receiving taxpayer funding to expand their acceptance of these assessments. In addition, some industry certifications such as the Automotive Service Excellence (ASE) credential accept experience on the job as a substitute for classroom time in assessing competency. Learners who earn ASE certification receive an earnings boost comparable to that associated with a college degree. State governments should facilitate cooperation between community colleges and industry groups to develop more voluntary certifications that assess competency by measuring job experience and independent learning rather than classroom time.

- Overturn degree requirements in government policy. Government requirements are a major contributor to the societal practice of using college degrees as a prerequisite for employment. Credential inflation is at its most pronounced in the federal civil service, and state and local governments often require a college degree to obtain a license in many occupational fields. These rules set up colleges as gatekeepers to many good middle-class jobs, allowing them to charge higher prices. Governments should eliminate degree requirements for all jobs where they are not a necessary signal of competency.

Evaluating Current Legislative Proposals

Several pieces of legislation aim to address the causes of tuition inflation. In 2017, House Republicans led by Rep. Virginia Foxx (R-NC) introduced the PROSPER Act, which would overhaul the federal role in higher education. The proposal contains several provisions that would tackle the causes of rising college costs. The bill introduces a long-overdue cap on Parent PLUS loans and pares back interest subsidies on undergraduate loans. These changes would constrain the future growth of tuition, though the bill could go farther by fully eliminating Parent PLUS loans and ending discontinuous increases to loan limits.

The PROSPER Act also makes some changes aimed at ensuring colleges provide value for money. It strengthens current accountability rules by making schools ineligible for federal student aid if large shares of their former students are consistently delinquent on their student loans. This could indirectly provide some price discipline, since schools would have more incentive to ensure students can afford their loans. But much stronger accountability rules would be necessary to put a significant dent in rising college tuition.

In addition, the PROSPER Act takes aim at barriers to entry in higher education. Though it preserves the current role of accreditors as gatekeepers, it undoes statutes requiring them to consider inputs to higher education such as curricula, faculty, and facilities, and instead requires accreditors to assess student learning and other outcomes. Such a shift in focus from inputs to outcomes will open the door for high-quality but lower-cost institutions of higher education to access federal aid programs and compete with incumbent colleges.

Other legislative proposals are built around reforming the accreditation system, which members of both parties see as a barrier to entry. Senator Mike Lee’s (R-UT) Higher Education Reform and Opportunity Act would allow states to accredit institutions of higher education. The plan would lower barriers to entry by allowing new institutions to bypass established private accreditors and gain access to federal financial aid. The bill pairs this expansion of accreditation with a risk-sharing framework to ensure institutions are financially accountable for student outcomes.

The Higher Education Innovation Act, introduced by Senators Michael Bennet (D-CO) and Marco Rubio (R-FL), allows the Department of Education to approve new “innovation authorizers” to act in parallel to accreditors and grant new institutions access to federal financial aid. Innovation authorizers would be required to hold their institutions to certain performance benchmarks, and they would be accountable for a percentage of the federal loans that students do not pay back. This would move federal accreditation policy further towards an outcomes-based framework.

Congress has also shown interest in improving price transparency. The 2021 Consolidated Appropriations Act shortened the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA), a longtime goal of retired Sen. Lamar Alexander (R-TN). Federal Pell Grant awards were previously based on a complicated formula involving income, wealth, and family size, which made it difficult for families to estimate aid amounts in advance. The change will simplify this formula and guarantee maximum Pell Grants to most low-income students, increasing the predictability of aid and taking small steps toward greater price transparency. However, institutional aid awards remain unpredictable and opaque.

The College Transparency Act, sponsored by a bipartisan group including Senators Bill Cassidy (R-LA) and Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), tackles the price opacity issue more directly. The bill would repeal the ban on a student unit-record data system, allowing the government to collect and release much more precise data on the cost of college. The legislation would allow much more accurate estimates of net price before students even apply to college, improving students’ and families’ ability to comparison-shop. The bill also requires the release of better data on outcomes like graduation rates and post-college earnings, providing more information on value for money.

Conclusion

An in-state student at a public four-year college will pay 77% more for college than she would have 20 years ago. While federal and state governments have increased financial aid, increases in underlying college costs mean that support amounts to running faster to stay in place. If colleges and universities had instead held their costs to a reasonable level, that aid could instead have been used to reduce tuition and even help defray living expenses for the neediest students. Growth in administrative and academic support spending is primarily responsible for cost increases at colleges, though instructional spending also contributes a significant amount.

In competitive industries, market forces tend to reduce prices over time. However, this has not happened in higher education due to a combination of factors. Barriers to entry, price opacity, federal financial aid, and a general feeling that college is necessary to succeed in life all contribute to keeping prices high. To bring down the cost of college, policymakers should attack these aspects of the higher education system and allow the pressures of a competitive market to relieve the financial burden on college students and their families.