As the year winds down, it is a good time to reflect on how inflation inequality evolved as inflation steadily declined from a 40-year high. Even as inflation has declined, inflation inequality across income groups has steadily risen, which is a factor that may have contributed to the 2024 election. Indeed, data from this year paint a stark picture of inflation inequality, showing why the recovery must consider the bottom of the income distribution.

Inflation hits harder at the bottom

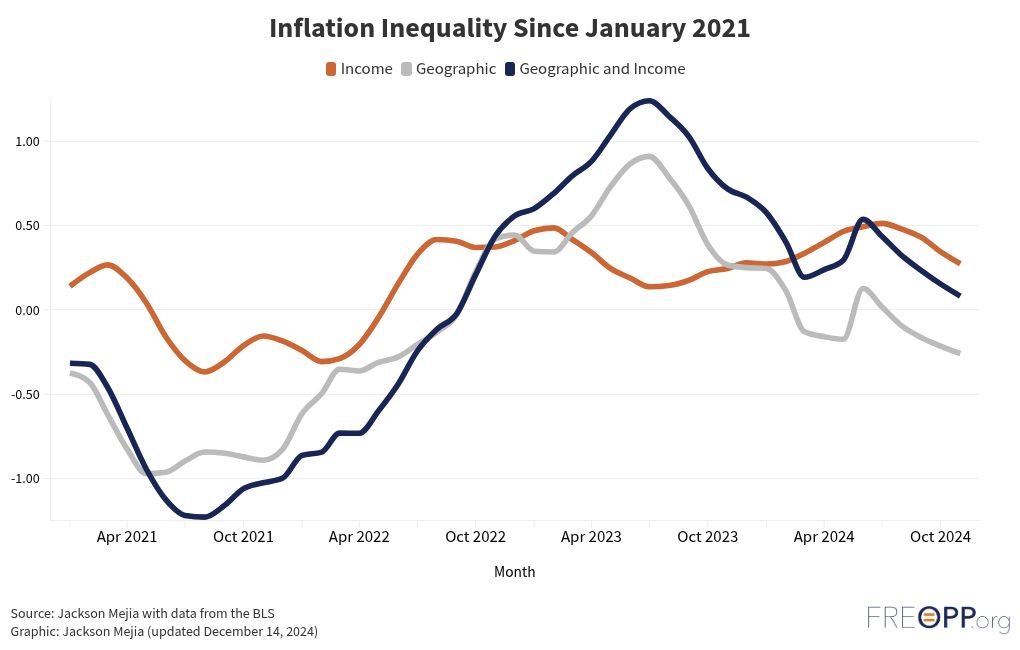

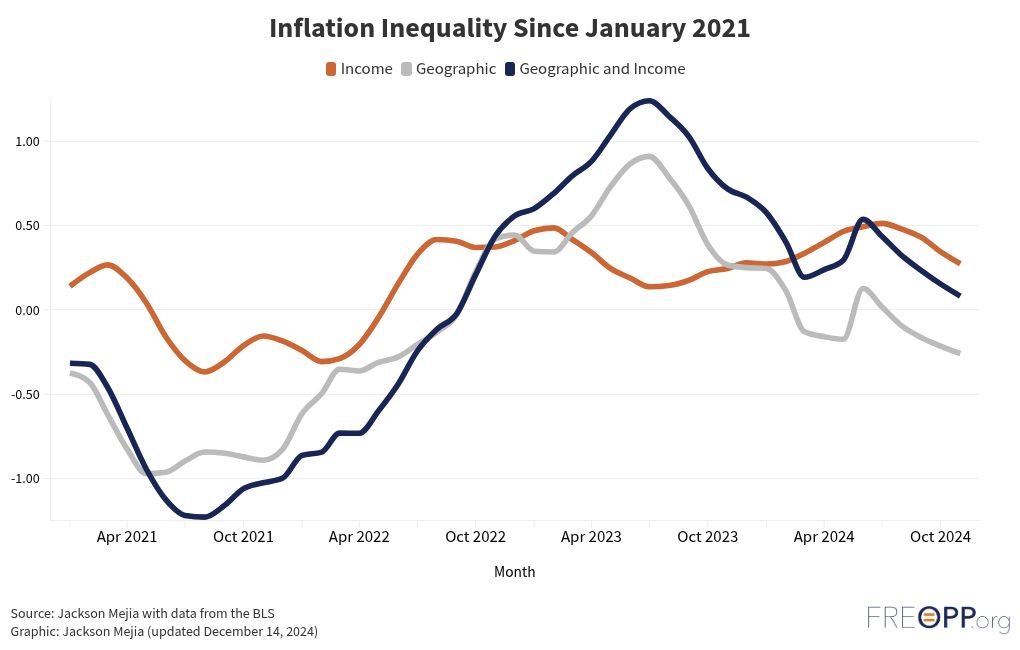

During the 2024 presidential campaign, inflation consistently dominated the narrative. While inflation dropped considerably in 2024, it did not for the entirety of the income distribution. Figure 1 (“Inflation Inequality Since January 2021”) plots inflation inequality by income decile since January 2021 for the second, fifth, and top deciles of income. The first decile is omitted because it is a mix of retirees, business owners, and low-income households. Since inflation peaked, the bottom of the income distribution has consistently faced the highest inflation rates. Indeed, since early 2023, the gap between the top and bottom is considerable.

The inflation inequality disparity is clear in Figure 2 (“Inflation by Income Decile”) which shows inflation from November 2023 through November 2024. Despite the Fed’s goal to hit two percent inflation, not a single income group is within 50 basis points of that figure. More damningly, aside from the bottom quartile, the average inflation rate monotonically decreases from the second decile downward. That means the lowest income groups have consistently faced higher inflation for the last year. Indeed, the gap is over 70 basis points between the second and top income deciles, which is larger than the gap the Fed needs to cover to get down to its two percent goal.

Inflation across regions: not just an urban problem

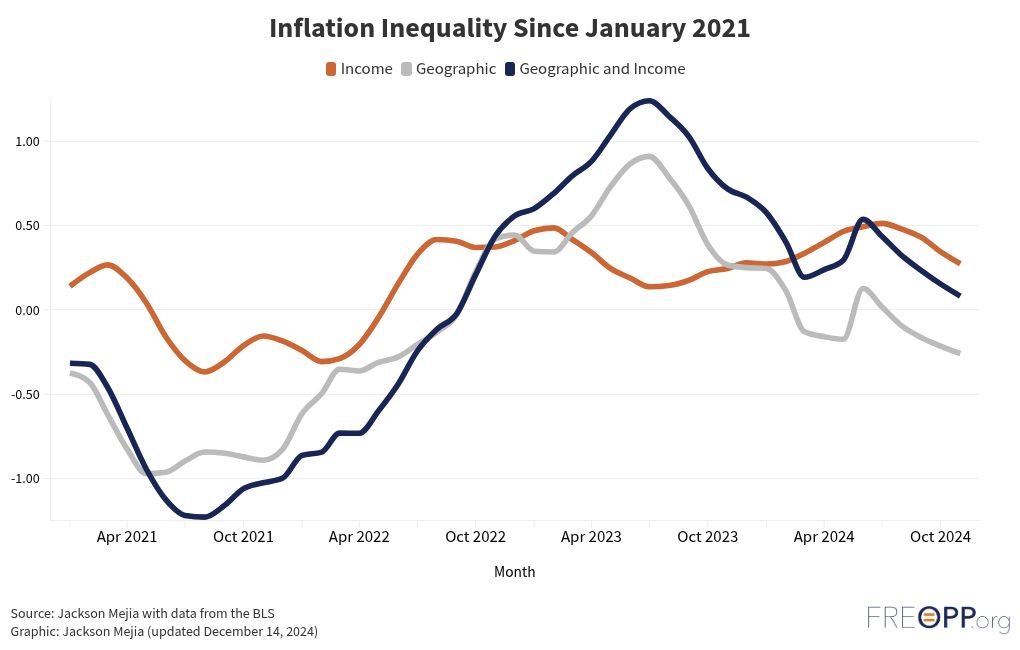

The inequality story isn’t just about income: it’s also about where people live. Figure 3 (“Inflation Rate by Income Quartile and Census Division”) reveals that regions in the Census like the Mountain West (Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming) and East South Central (Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Alabama) divisions faced the sharpest inflation spikes in the peak of the 2021 inflation, but have had low inflation relative to the rest of the United States since then. Indeed, both regions have seen inflation well-below the Fed’s two percent target in recent months. These areas often rely more on energy and agriculture, which are sectors particularly vulnerable to the supply-chain shocks that plagued the economy in 2022 and 2023, but have since subsided.

For low-income households in high-inflation regions, the situation is doubly challenging. Regional inflation disparities deepen the inequality between rural and urban areas and highlight why national policies often fail to address localized struggles.

Long-term inequality: the compounding effect

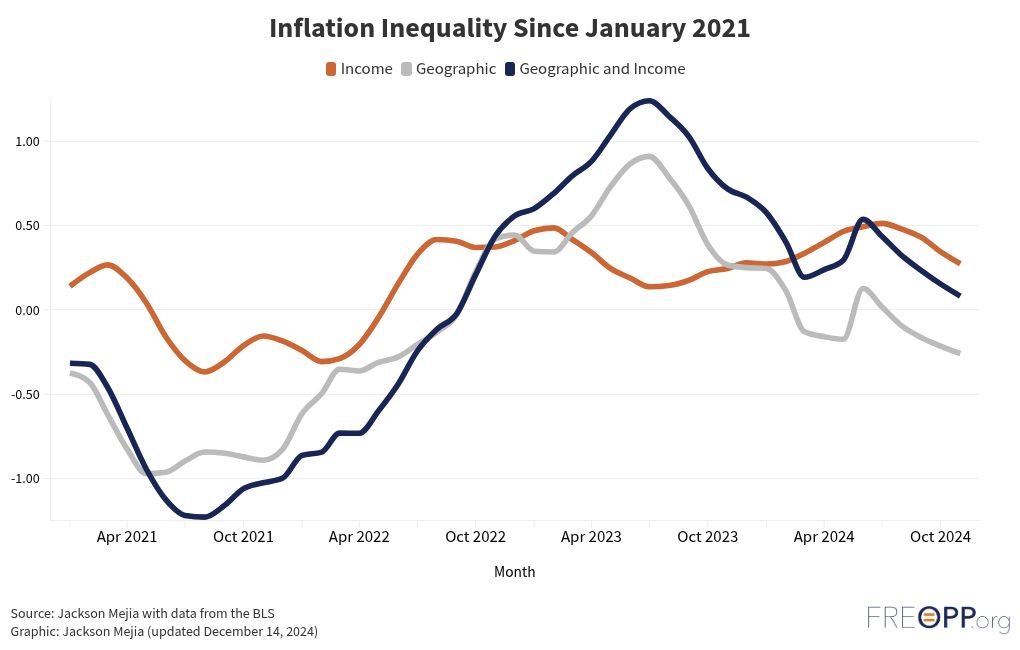

One of the most striking takeaways from this year’s data is the cumulative effect of inflation inequality. Figure 4 (“Cumulative Inflation Inequality Across Income and Geography”) underscores this, showing how inflation has widened gaps over decades. Households in the bottom income quartiles have endured significantly higher cumulative inflation since the 1980s, creating a persistent drag on their economic mobility.

Similarly, geographic disparities have compounded over time. Regions like the Pacific (Alaska, California, Hawaii, Oregon, and Washington) have seen consistently higher inflation for a long time, although much of that is due to local factors like housing policy rather than anything that could easily be fixed by federal action.

Putting the income and geographic inequality leads to Figure 4 (“Cumulative Inflation Inequality Across Income and Geography”), which shows that the combination of geographic and inflation inequality has compounded considerably in the last 40 years. At the same time, despite the appearance of large inflation inequality during the last two years, it is not considerably different from the previous 30 years.

The path forward for anti-inflation policy

With inflation cooling, there’s a growing debate about whether interest rates should come down further. While lower rates could stimulate growth, they risk reigniting price pressures in ways that would disproportionately hurt low-income households.

But reducing interest rates alone won’t solve inflation inequality. By their very nature, interest rates are blunt tools that cannot address the structural issues causing inflation inequality. All the Fed can do is more carefully consider the bottom of the distribution when deciding on rate decisions and leave the rest to the federal government.

Inflation inequality isn’t new, but the past few years have laid it bare for all to see. As we move into 2025, the data reminds us that inflation varies dramatically depending on income and location. By putting these disparities at the forefront of policymaking, we can ensure that the next chapter of economic recovery is more equitable—and more resilient—for everyone.