Inflation inequality in the age of Trump

Photo by Erol Ahmed on Unsplash

We now have the first results of a full month of inflation data under President Trump. Even as aggregate inflation has stubbornly remained above the Federal Reserve’s two percent target, inflation inequality has shrunk between income groups and risen between geographic regions. That plays some role in the Fed’s increasingly difficult decision about what to do about interest rates, especially in the face of rising uncertainty and the threat of tariffs.

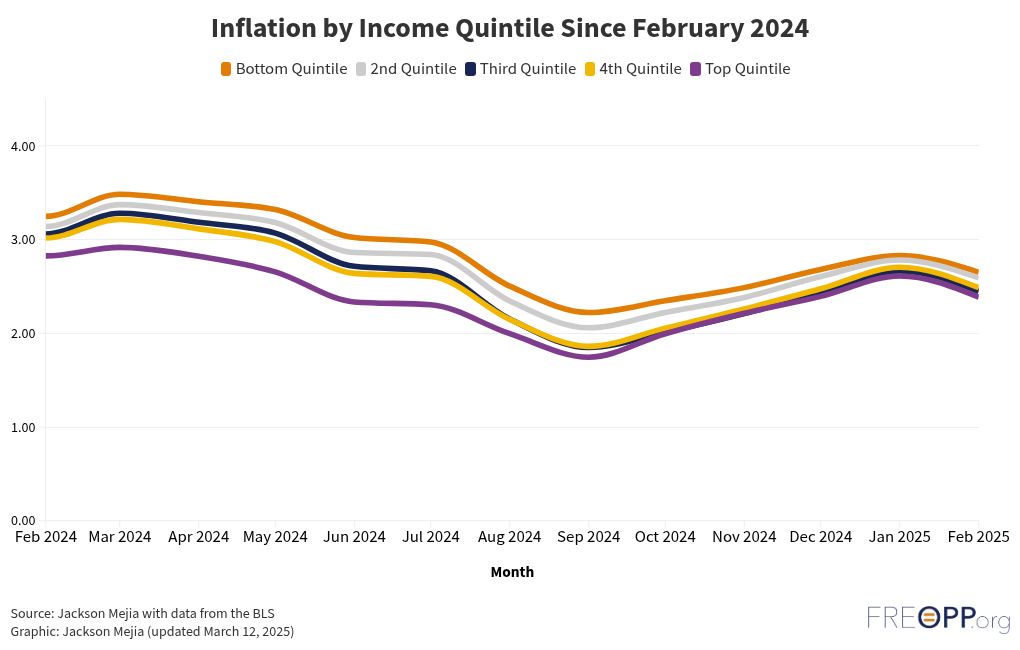

The below figure illustrates inflation by income quintile since February 2024. For the last twelve months, the poorest quintile has faced the highest inflation in every month. In fact, the level of inflation has been consistently ordered by income for the last year. Cumulatively, that contributes to prices thirty basis points higher for the lowest quintile than the top quintile.

The persistently higher inflation is particularly bad because low-income households are worse off than high-income households for the same rate of inflation. That is because they typically already have lower budgets and lower savings, so any increase in their prices hurts them even more. Moreover, they typically devote a larger share of their budget to essentials like food, housing, and transportation, which are disproportionately affected by rising prices. Goods like these tend to exhibit inelastic demand, meaning that even slight price increases can significantly erode purchasing power. As a result, the persistently higher inflation rates they face are particularly bad and must be considered in forthcoming policy decisions.

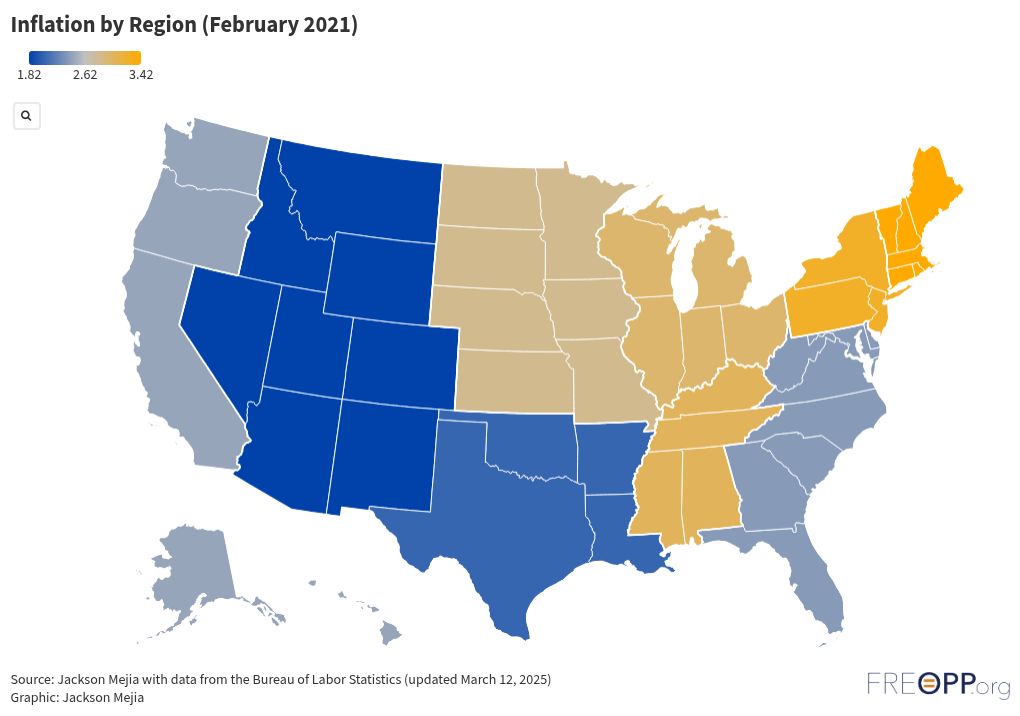

The next figure provides a complementary perspective by focusing on geographic disparities. Figure 2 plots inflation by Census region across the United States in February. There is an even more significant gap here than for income inflation inequality. Whereas the Mountain West, encompassing states like Montana, Idaho, Colorado, and Arizona, have seen prices rise by about 1.8 percent compared to the same time last year; the Northeast and New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania tri-state saw prices rise by nearly 3.5 percent since last year. The middle of the country has been squarely between the extremes.

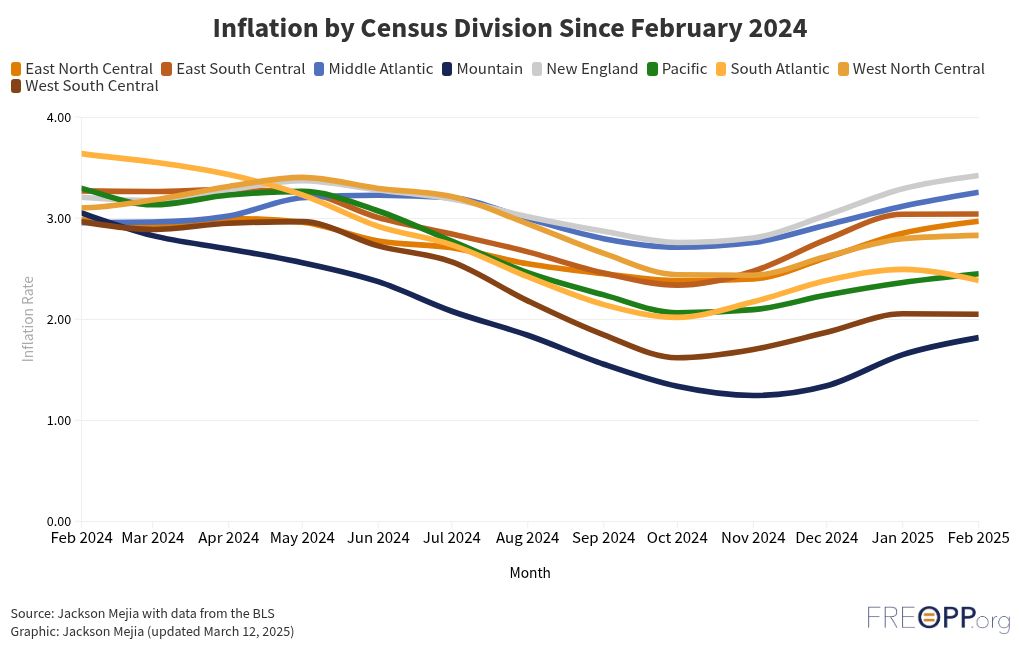

Figure 3 (below) shows that the regional inflation disparity has been large and growing since last year. Last February, the difference between the highest and lowest inflation regions was around 75 basis points. Now, it is more than double that.

The large inflation disparities at the income level and the even larger disparities at the geographic level present a challenge to monetary policy. Conventional monetary policy tools, such as adjustments to the federal funds rate, are typically designed around aggregate data. When regional differences are pronounced, a one-size-fits-all policy risks undercutting some areas while leaving others exposed to runaway prices. This heterogeneity forces policymakers to consider whether targeted interventions—potentially coordinated with fiscal authorities—might be required to address localized inflationary pressures. However, it is unclear whether targeted interventions would be wise or possible.

The Fed’s challenge is compounded by uncertainty over tariff policy. A rise in tariffs would generate a one-time inflationary spike equivalent to a negative supply shock, and the Fed may see itself as needing to intervene. But continuous tariff volatility has only heightened the dilemma faced by monetary policymakers and paralyzed them into a position which offers them flexibility but also makes the situation worse by heightening economic uncertainty.

The combination of monetary policy uncertainty with fiscal policy uncertainty creates extra issues for the private sector. When firms are unsure about future monetary policy or the persistence of inflation, they tend to postpone or scale back investment decisions due to fears of capital mis-allocation and diminished returns on new projects. This hesitancy can stifle growth—the very outcome a rate cut might aim to prevent—thereby complicating the broader objectives of economic recovery and job creation. In this environment, any decision to adjust rates must carefully weigh the risk of undermining investor confidence and long-term innovation against the need for immediate economic stimulus.

As households—particularly low-income households—continue to suffer from high inflation and the threat of tariffs, the Federal Reserve must make a decision. Trade-offs abound in any policy decision, but a failure to act threatens the economy almost as much as the wrong decision.

">

">