Executive Summary

On Tuesday, December 10th, FREOPP hosted a half-day conference on reducing the costs of hospital care in the United States, headlined by an appearance by Seema Verma, the Administrator for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Bringing together a consortium of leading scholars across the political spectrum, “Affordable Hospital Care Through Competition” offered bipartisan paths forward on lowering costs, improving access and ensuring quality for every patient.

Further reading from FREOPP on the topics covered at the conference:

Welcome & introduction

To kick off the event, Jonathan Bush, the Executive Chairman of Firefly Health and the founder of athenahealth, discussed how patients suffer the most when hospitals monopolize a market. As an entrepreneur, he emphasized the power of new entrants – and competition — into the care delivery market to revolutionize the way Americans receive medical care. Bush described how Firefly Health is attempting to do this, by providing health navigation and concierge medicine to patients outside of the brick and mortar of a hospital campus and meet them in their home. Following Bush’s remarks, FREOPP President Avik Roy spoke on the necessity of inducing more competition into an increasingly consolidated — and uncompetitive — hospital market as an essential piece to building affordable health care for every generation. With these themes in mind, economists and policy experts delivered presentations on the depth of the problem of high hospital prices, and potential policy solutions.

Making the case: The rising cost of hospital care

Professor Ge Bai of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health emphasized that there is no evidence that more profitable non-profit hospitals provide more charity care or greater community benefits than less profitable ones. In essence, non-profit hospitals are required to give back to their communities, especially when they hold a monopoly on the market, or else face pressures of losing their tax-exempt status. Bai’s work also emphasized the ability of regional hospital monopolies to charge higher markups for procedures, with certain specialties, such as anesthesiology, charging 5.8 times the median charge-to-Medicare payment ratios. Professor Bai has written on a multitude of topics, with a keen eye on the increasing costs to patients when hospitals or providers monopolize a market.

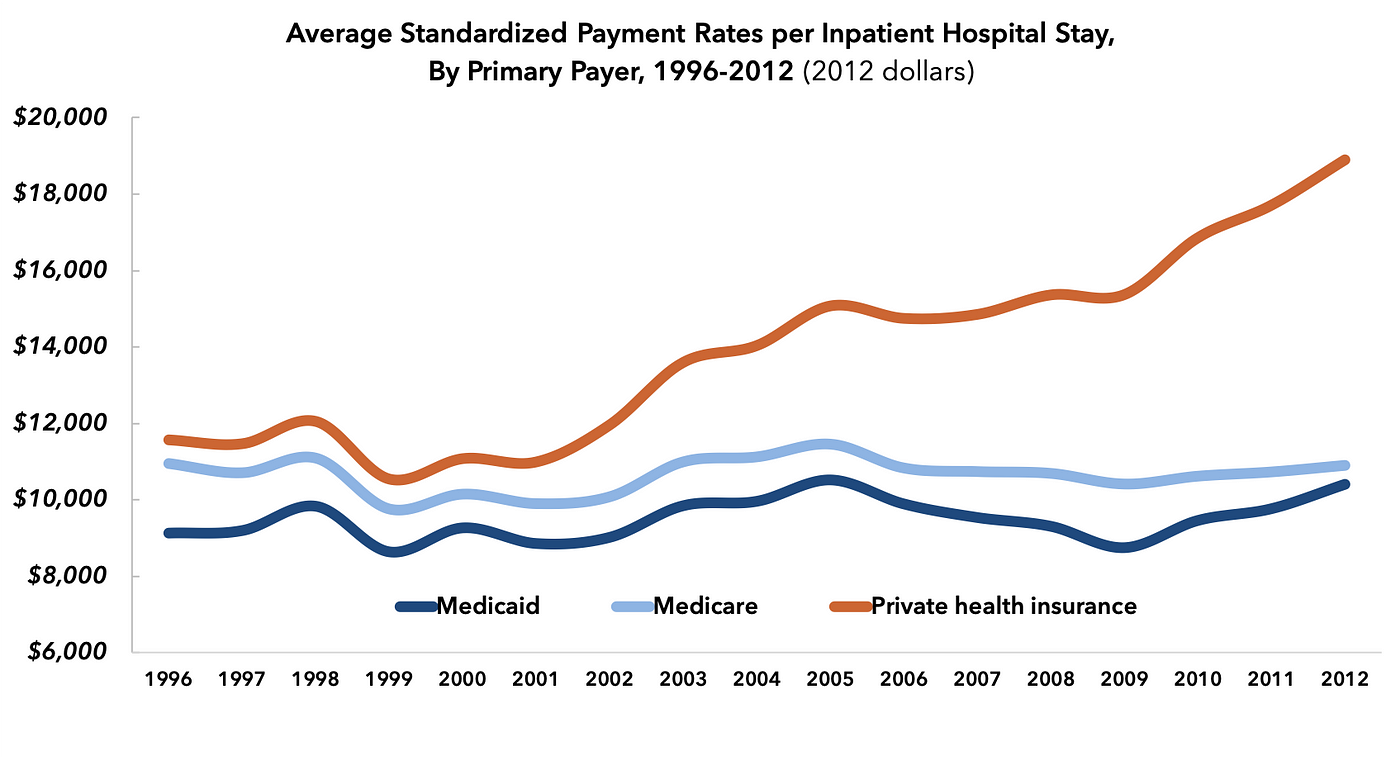

Similarly, Tara O’Neill Hayes, deputy director of health care policy at the American Action Forum, explained that hospital prices are growing much more quickly than physician prices, as hospital prices for all inpatient care grew 42% while physician reimbursement for that care grew just 18% between the years of 2007 and 2014. Tara also noted that despite the attention astronomical pharmaceutical prices have received in the news, the country collectively spends nearly 450 percent more on hospital care than prescription drugs, evidencing that in order to bend the health care cost curve, addressing the rising costs of hospital care must be paramount.

Additionally, Bill Johnson, a senior researcher at the Health Care Cost Institute (HCCI), presented findings from HCCI’s annual Health Care Cost and Utilization report, which uses claims data from four national health insurance companies to track per-person spending and utilization of health care services. He then shared data from HCCI’s Healthy Marketplace Index to compare different metro areas on hospital concentration using the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI), noting that hospital market concentration increased in almost 70 percent of metro areas from 2012 to 2016, showing a positive correlation with increased price indexes as well. In sum, more size translated to more pricing power for hospitals over the average patient.

Building on Johnson’s points that increased market concentration led to higher patient costs, Chapin White, a senior policy researcher at the RAND Corporation, noted how rising prices was evident with both for-profit and not-for-profit hospital networks, echoing Bai’s earlier sentiments. In essence, even with the tax-exempt status shared by non-profit health systems, there was no evidence that non-profit hospitals held prices in check, especially after consolidation. White also noted that in reviewing non-profit hospital spending, only 2 to 5 percent of their annual budget was allocated for charity or for community benefits – which they are required by federal law to do in order to maintain their tax-exempt status. Lastly, noted the need for transparency in evaluating Medicare-certified hospitals for CMS oversight, which he produced with RAND in 2018.

Solutions from the policymakers

During this session, FREOPP welcomed U.S. congressmen Jim Banks (R., Ind.) and Bruce Westerman (R., Ind.), alongside Marilyn Bartlett of the National Academy for State Health Policy to the stage. For Rep. Banks, the issue of hospital consolidation leading to increased rates for patients was a personal one after reading about the Parkview View Health System, a Fort-Wayne based health system in Banks’ home district, in a New York Times article showing how hospitals charged double or even triple Medicare rates when no competition is present within a market. This led to Reps. Banks and Westerman co-sponsoring the Hospital Competition Act of 2019, aimed at freezing the practice of hospital consolidation by bolstering the Federal Trade Commission’s enforcement of the Sherman Antitrust Act alongside other key provisions to restoring a competitive national hospital market.

Additionally, Rep. Westerman spoke about his introduction of The Fair Care Act of 2019 aimed at reducing federal spending while expanding coverage for all Americans. In addition to addressing hospital consolidation, Westerman also spoke of the need to strengthen the McCarron-Ferguson Act in order to address the other side of the coin, health insurance consolidation. Both Reps. Banks and Westerman agreed that allowing patients to choose how their health care dollars are spent, through a more price-transparent marketplace with robust competition, would allow patients to receive more affordable health care.

Bartlett helmed the State of Montana Employee Benefit Plan in 2014, and moved the plan from projected reserves of negative $9 million to positive $112 million in less than 3 years, by deploying tough negotiating tactics with insurers and hospitals. In her remarks, she noted the importance of price transparency, in order for the patients to understand how their health care dollars are spent based on her work in Montana. Bartlett’s sentiments would be echoed repeatedly in the panel that followed.

Solutions from the wonks

Emily Gee, a health economist at the Center for American Progress (CAP), highlighted CAP’s 2018 report, Provider Consolidation Drives Up Health Care Costs, which recommended that the Federal Trade Commission boost its enforcement authority of horizontal mergers and update the standards for vertical merger review. The report urged states to repeal laws that restricted the supply of health care providers, such as scope-of-practice laws, while emphasizing the importance of Medicare moving toward site-neutral payments to hospitals and physician offices. It also recommended that Congress cap the rates that providers can charge and ban providers from balance billing patients.

In addition, Brian Blase, the former Special Assistant for Economic Policy at the National Economic Council, discussed ways in which the Trump administration has used its regulatory authority to bring down heath care costs for Americans. Most notably, Brian led the process to implement the Trump Administration’s Executive Order that resulted in an expansion of Health Reimbursement Arrangements (HRAs), offering a new coverage options for American workers, which was applauded by many on the panel, including Roy. Additionally, Blase also led the process to implement an executive order that President Trump signed in October 2017 that resulted in three final regulations to expand affordable health coverage options for employers and families and a comprehensive report: Reforming America’s Health Care System Through Choice and Competition.

Lastly, Joel White, President of the Council for Affordable Health Coverage, noted the daunting burden of medical costs on the average American family. By 2030 the average family will pay 40 percent of their income on healthcare. White also noted that of the total health care spending in America, nearly 53 percent goes towards hospital care (33 percent) and physician and clinical services (20 percent), which may become even worse in the future as the trend toward hospital consolidation continues, with 72 percent of all metro area hospital markets considered highly concentrated (i.e. monopolistic or oligopolistic). In his closing remarks, White echoed Gee’s plea for increasing funding and staffing for the Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission, who are responsible for overseeing the legality of these mergers and acquisitions.

Seema Verma on Trump administration efforts to curb rising hospital costs

To end the day, CMS Administrator Seema Verma sat down with Avik Roy for a fireside chat to discuss the Administration’s efforts to usher in price transparency and competition, in order to make hospital care more affordable for all Americans. As seen with CMS’s price transparency rule issued on November 15, Administrator Verma and CMS are committed to improving price quality and transparency, stating: “Everything we do at CMS is about reducing cost of care and growth of costs, while keeping innovation in our country.” To this end, Verma and Roy spoke about the successes seen within Medicare Advantage and its ability to balance competition within a federal framework. As noted by Verma: “I love Medicare Advantage, because it epitomizes competition.” In short, Medicare Advantage served as a case study in how a competitive market ultimately benefited patients.

Additionally, Administrator Verma noted the importance of stakeholders – outside of the government – making their voice known to CMS in order to help inform their decision-making. She encouraged citizens, academics, patient advocates and industry voices to help inform officials in Baltimore about their experiences from around the country.

Conclusion

As the conference adjourned, there was a clear consensus amongst liberals, conservatives, and libertarians: more hospital competition will translate to lower prices for patients. There are few areas in health policy that unite all ends of the political spectrum, but this issue — which impacts all of us and our loved ones — may be one of them.