Executive Summary

A quasi-consensus has emerged among many policymakers and commentators that the U.S. should continue to close schools and non-essential businesses until coronavirus testing and immunity is widespread. But there is a significant possibility that we are many months, if not years, away from meeting these thresholds. Time is of the essence, given the severe human cost of a prolonged economic shutdown.

The good news is that policymakers have an opportunity to strategically reopen the economy, by taking into account a unique feature of COVID-19: its heavy skew toward bad outcomes in the elderly and the near-elderly who also have other chronic diseases. With the proper precautions, and the deployment of tools like contact tracing, self-quarantines, and telemedicine, we can continue to protect the most vulnerable, while returning as many Americans as possible to work.

We will still need to address high-risk populations in congregate settings, like nursing homes, rehabilitation facilities, jails, and prisons. Nearly half of all U.S. COVID-19 deaths have taken place in nursing homes and assisted living facilities. But we are persuaded that much more can be done to reopen the economy today, thereby improving the lives of hundreds of millions of low-to-middle income Americans.

(Authors’ note: This is a working paper that was updated 11 times between April 20 and August 24, 2020 with new evidence and policy ideas. Revisions are noted at the end of the paper.)

Introduction

Deaths and hospitalizations are continuing to rise in the United States from COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, albeit more slowly than before. Many policymakers and members of the public have expressed the hope that life will be “back to normal” by May or June. But it won’t be. Indeed, life may never return to exactly the way it was before 2020.

And that is the optimistic scenario most widely articulated by public health commentators, in which the U.S. successfully “flattens the curve,” establishes nearly ubiquitous testing, and succeeds at rapidly developing treatments and vaccines for SARS-CoV-2. A recent paper published by former FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb and others at the American Enterprise Institute outlines this scenario.

This optimistic scenario leaves us concerned that the public, the media, the business community, and policymakers are largely unprepared for a pessimistic scenario in which accurate, near-ubiquitous testing is difficult to achieve; infected individuals’ antibodies do not lead to immunity; anti-viral treatments take longer to develop; and vaccines never arrive.

We are concerned that the public, the media, the business community, and policymakers are largely unprepared for a pessimistic scenario in which near-ubiquitous testing is difficult to achieve, infected individuals’ antibodies do not lead to immunity, anti-viral treatments take longer to develop, and vaccines never arrive.

Under the present policy paradigm, many commentators and policymakers argue that something resembling the pessimistic scenario will require a prolonged shutdown of six months or longer, or an indefinite series of on-and-off stay-at-home orders that could go on for years.

As Morgan Stanley biotechnology research analyst Matthew Harrison put it in an April 6 op-ed, “Hope that…the U.S. has not reached crisis levels…will be shortlived, as the reality sets in that the path to reopening the U.S. economy is going to be long, and marred by stops and starts. It will be fully resolved only when vaccines are widely available in spring 2021, at the earliest.”

But the U.S. economy cannot sustain a shutdown of that magnitude, nor the permanent closure of tens of thousands of businesses that will accompany it.

Several features of SARS-CoV-2 and the COVID-19 disease lead us to believe that there is at least a 30% chance that the pessimistic scenario unfolds instead of the optimistic one, or — more precisely — that the optimistic scenario will take too long to play out.

Hence, it is essential that we develop a strategy to reopen the economy for both the optimistic and pessimistic scenarios, as well as for a spectrum of intermediate scenarios: that is to say, even if we fail to achieve near-ubiquitous testing, effective anti-viral treatments, and a vaccine. In this working paper, we discuss a plan to do that.

Ubiquitous testing may be difficult to achieve in the near term

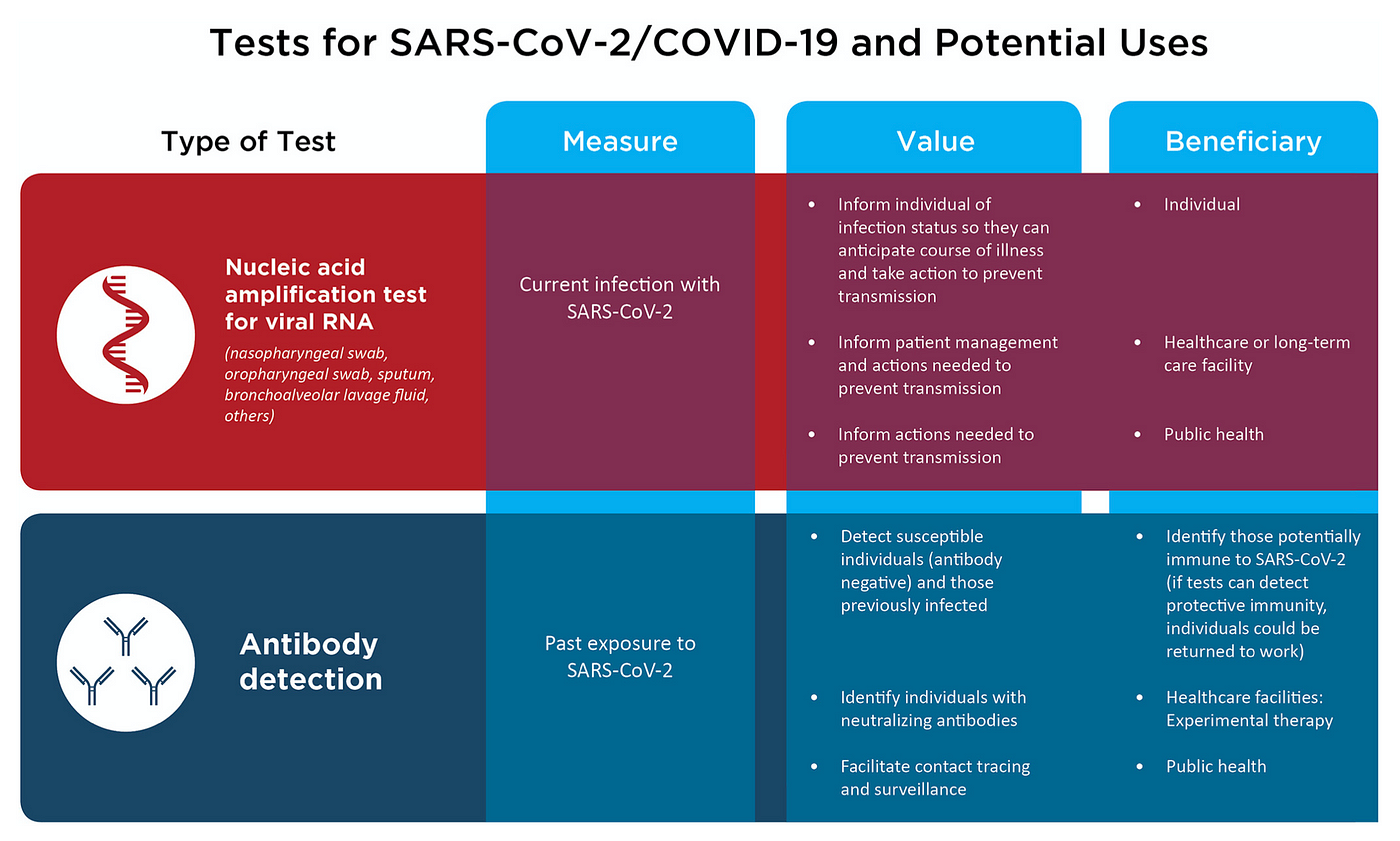

At this time, there are two principal kinds of tests for SARS-CoV-2: antibody-based or serology tests that detect if a patient has developed antibodies to the virus; and reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) tests, which measure viral RNA levels in a patient’s nasal secretions. Both forms of testing have significant technical limitations.

Statistically speaking, most antibody-based tests currently yield too many false negative cases, in which infected people go undetected, to be useful for population-wide surveillance.

Most patients only begin developing detectable levels of antibodies between 7–11 days after exposure to SARS-CoV-2. Hence, people who have yet to test positive on serology can in fact be infected and be infecting others.

For example, the latest IgG antibody test from Abbott Laboratories is best at detecting the presence of antibodies two weeks after a patient complains of COVID-19 symptoms, but can yield a high false negative rate, or low sensitivity, before then, dropping down to 50% three days after COVID-19 symptoms. On top of that, there is some evidence that many people infected with SARS-CoV-2 do not ever develop detectable levels of anti-coronavirus antibodies.

SARS-CoV-2 antibody tests will also need to reach a specificity, or true negative rate, above 99.5% to be useful on a mass scale. That is to say, for every 100,000 uninfected people, the test will correctly identify all but 500 of them.

RT-PCR, which measures viral RNA levels in a patient’s nasal secretions, has more accuracy, especially at detecting active infections. But RT-PCR is more difficult to scale up quickly, because RT-PCR is more labor-intensive to administer, and is much more expensive than a conventional blood test.

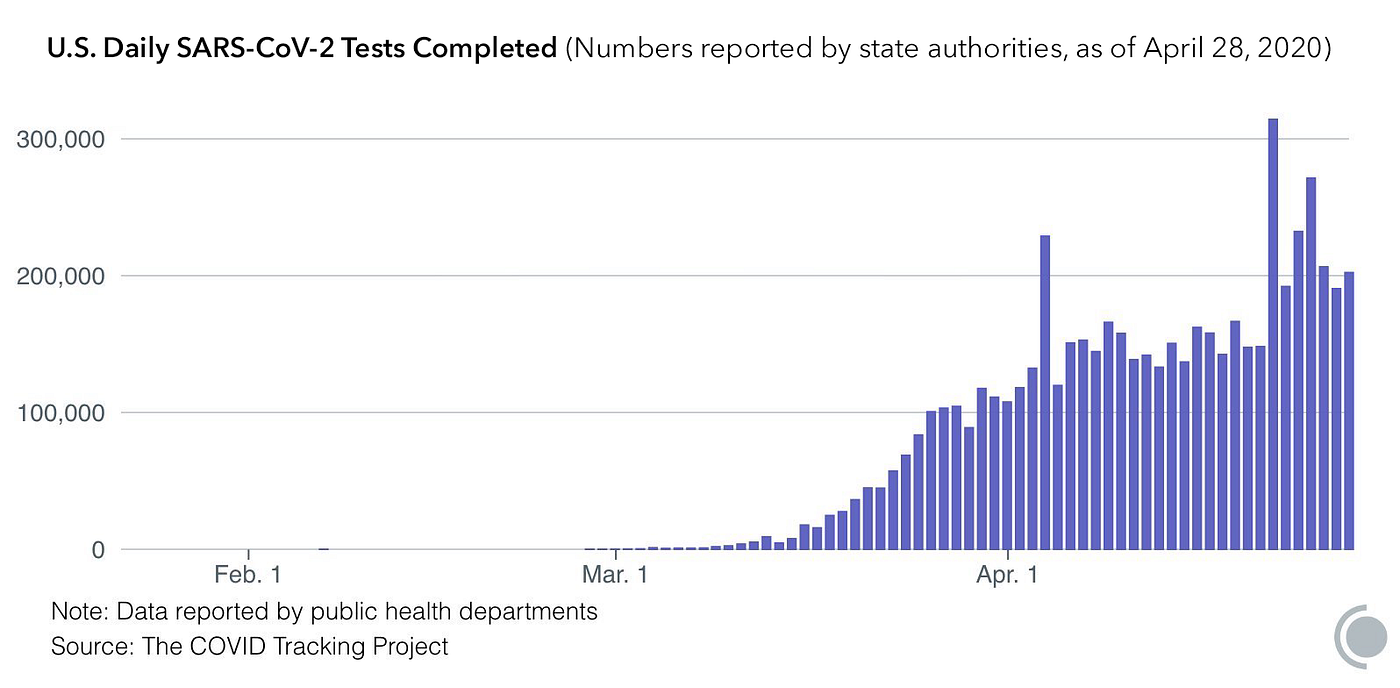

On March 27, Abbott Laboratories announced the emergency use authorization of a PCR-based SARS-CoV-2 test that it can manufacture at a rate of 50,000 per day. That would be a meaningful boost to U.S. testing levels—at the end of April, the U.S. was testing around 200,000 individuals per day, counting both serology and PCR. PCR tests, however, generally must be administered in clinical settings like a doctor’s office or an urgent care clinic. On April 21, LabCorp announced emergency use authorization for an at-home RT-PCR COVID-19 test kit, but due to scalability issues, LabCorp stated that they are only offering the kit to first responders and health care professionals for the time being.

And in order to reach South Korean levels of coronavirus testing, Matthew Harrison estimates that the U.S. will need to administer 1 million tests per day. In order to repeatedly screen the entire population, Nobel laureate economist Paul Romer estimates that the U.S. will need to reach 22 million tests per day.

Effective anti-viral treatments may take longer to develop

Historically, anti-viral medicines have proven much more difficult to develop than anti-bacterial medicines (a.k.a. antibiotics). While we now have effective medicines for HIV and hepatitis C, these took decades of research to commercialize.

According to the Milken Institute’s COVID-19 Treatment and Vaccine Tracker, there are over 150 treatments for COVID-19 in preclinical or clinical trials. While there is great reason to hope that some of these trials will eventually deliver us an effective treatment against the COVID-19 disease, there is no guarantee that such a treatment will arrive soon.

There is preliminary evidence that convalescent serum exchange could help some patients, but there is no definitive evidence at this time, and even if properly randomized trials show benefit, serum exchange will be costly and difficult to scale.

Kevzara, an anti-arthritis agent also known as sarilumab, has been studied in COVID-19 patients, with the hopes that the drug could mitigate the inflammatory process that seems to make COVID-19 worse in many patients. But Kevzara manufacturers Regeneron and Sanofi announced on April 27 that the drug failed to demonstrate a benefit to patients.

Direct anti-viral treatments also have their drawbacks. On April 16, Adam Feuerstein and Matthew Herper of STAT obtained a confidential recording from a videoconference among University of Chicago clinicians who are participating in a clinical trial of remdesivir, a potential anti-viral treatment for SARS-CoV-2 developed by Gilead Sciences. The physicians expressed hope that remdesivir was helping to rapidly resolve COVID-19 symptoms in their patients. But optimistic reports from physicians at a single site of a clinical trial did not translate into full-fledged success for the broader study.

Indeed, a fuller picture of the remdesivir trial showed no benefit for severe COVID-19 patients. A greater proportion of remdesivir patients died at 28 days (13.9 percent) than placebo patients (12.8 percent), though this was not a statistically significant finding. A National Institutes of Health study of less severe patients found a modest but statistically significant benefit in recovery from hospitalization, with remdesivir patients recovering in 11 days on average vs. 15 for placebo.

On the basis of this somewhat positive result, the FDA issued an Emergency Use Authorization for remdesivir, and Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, declared remdesivir the “standard of care” for COVID-19 hospitalizations. Paradoxically, deploying remdesivir in all hospitalized COVID-19 patients will make it harder to conduct clinical trials of more effective agents that will no longer be compared to placebo.

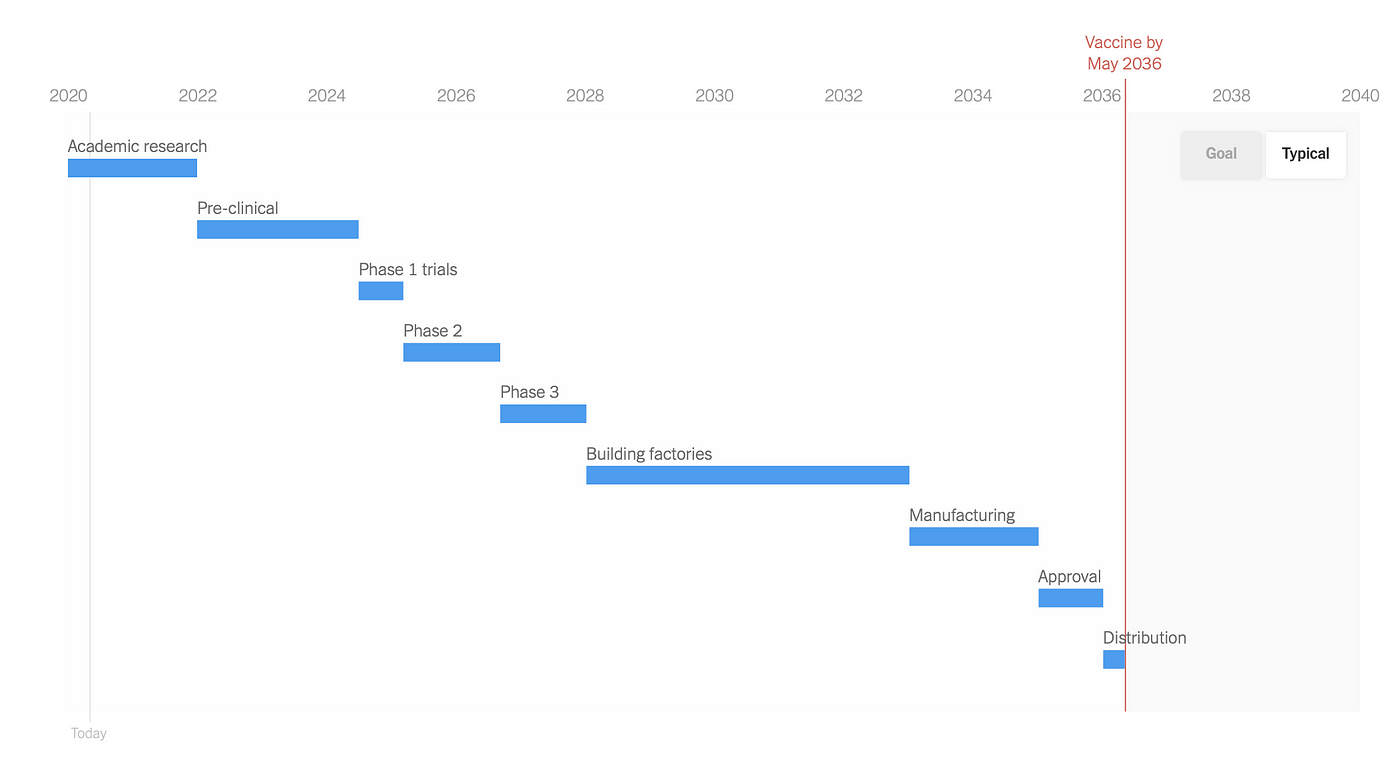

Vaccines may never arrive

While there have been several attempts, a successful vaccine has never been developed against a deadly coronavirus, including SARS-CoV-2 predecessors MERS (2012) and SARS-CoV-1 (2003). And while the biopharmaceutical industry is placing an extraordinary effort into developing a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, effort alone is no guarantee of success; witness our failure to develop vaccines for HIV or hepatitis C. Indeed, the fastest viral vaccine development program ever was for the Ebola vaccine, which took five years.

Most SARS-CoV-2 vaccine developers are targeting the spike glycoproteins that dot the surface of the spherical coronavirus particle. But glycoproteins—a combination of sugar and protein molecules—are especially good at evading the human immune response.

Many commentators are assuming that antibodies generated by infected patients will protect them from being re-infected with SARS-CoV-2. It is likely that antibodies are protective, but we do not know the extent to which this is true.

Based on experience with the 2003 SARS pandemic, many experts believe that anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies are likely to be at least partially protective. But an absence of complete protection would make it challenging to put workers into high-risk situations. A larger challenge is that, due to shelter-in-place measures, most Americans are unlikely to have been infected for many months; hence, over the near- to mid-term, most Americans will remain highly susceptible to this very contagious virus.

In fact, little is known about whether anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies are neutralizing; i.e., protective against subsequent infection. “Right now, we have no evidence that the use of a serological test can show that an individual has immunity or is protected from reinfection,” said Maria van Kerkhove, the COVID-19 technical lead for the World Health Organization, at an April 17 press conference.

There are few reports around the world of individuals suffering from COVID-19 on two separate occasions, but they are beginning to emerge. On August 24, 2020, researchers at the University of Hong Kong reported a confirmed case of reinfection, in which the genetic sequence of the virus in the second infection significantly differed from that in the first.

Reinfection is not unprecedented; individuals infected with HIV often possess large quantities of anti-HIV antibodies in their serum that have no effect on the HIV virus or the progression of AIDS. People often develop antibodies to the common cold, which is also a coronavirus, but those antibodies rarely confer immunity beyond one year, if at all.

Americans are optimistic by nature, and the public is well within its rights to hope for the best. But policymakers must prepare for the worst. And that means that we must consider options for reopening the economy in a world in which we have not completely controlled the COVID-19 pandemic.

Time is of the essence

Moody’s Analytics estimates that in only a few weeks’ time, stay-at-home orders have reduced U.S. economic output by 29 percent. Congress has spent over $2 trillion, and the Federal Reserve even more, to prop up the economy merely through the month of April.

Small businesses employ nearly half of all U.S. workers. A 2016 study by the JPMorgan Chase Institute found that “most small businesses hold a level of cash reserves that would provide an insufficient cushion in the face of a significant economic downturn or other disruption,” with the median small business holding 27 days’ worth of cash in reserve.

A study by researchers at the University of Illinois, Harvard, and the University of Chicago estimates that 100,000 small businesses have already permanently closed, with more closures to come. The Paycheck Protection Program, a Congressional relief package passed in late March, helped some small businesses, but most were either not savvy enough or not qualified to draw down federal funds. For example, businesses are not eligible for PPP loan forgiveness unless they maintain their payroll; but for many businesses, maintaining their payroll means they will run out of cash.

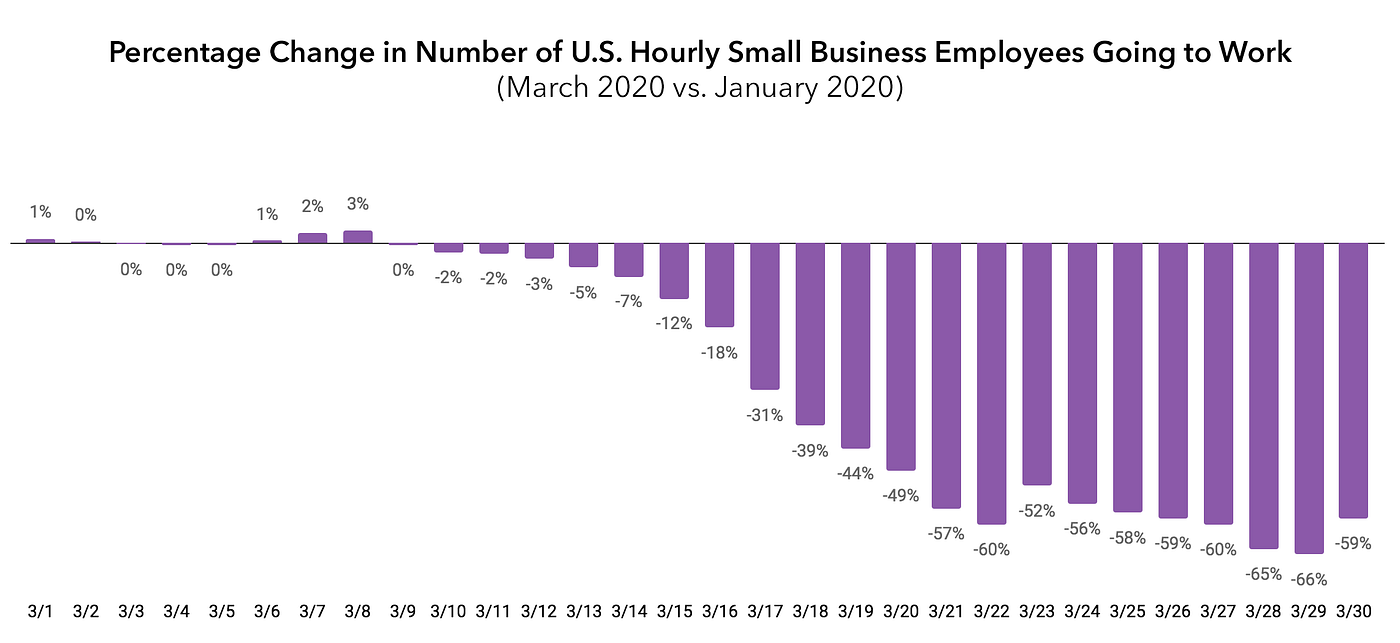

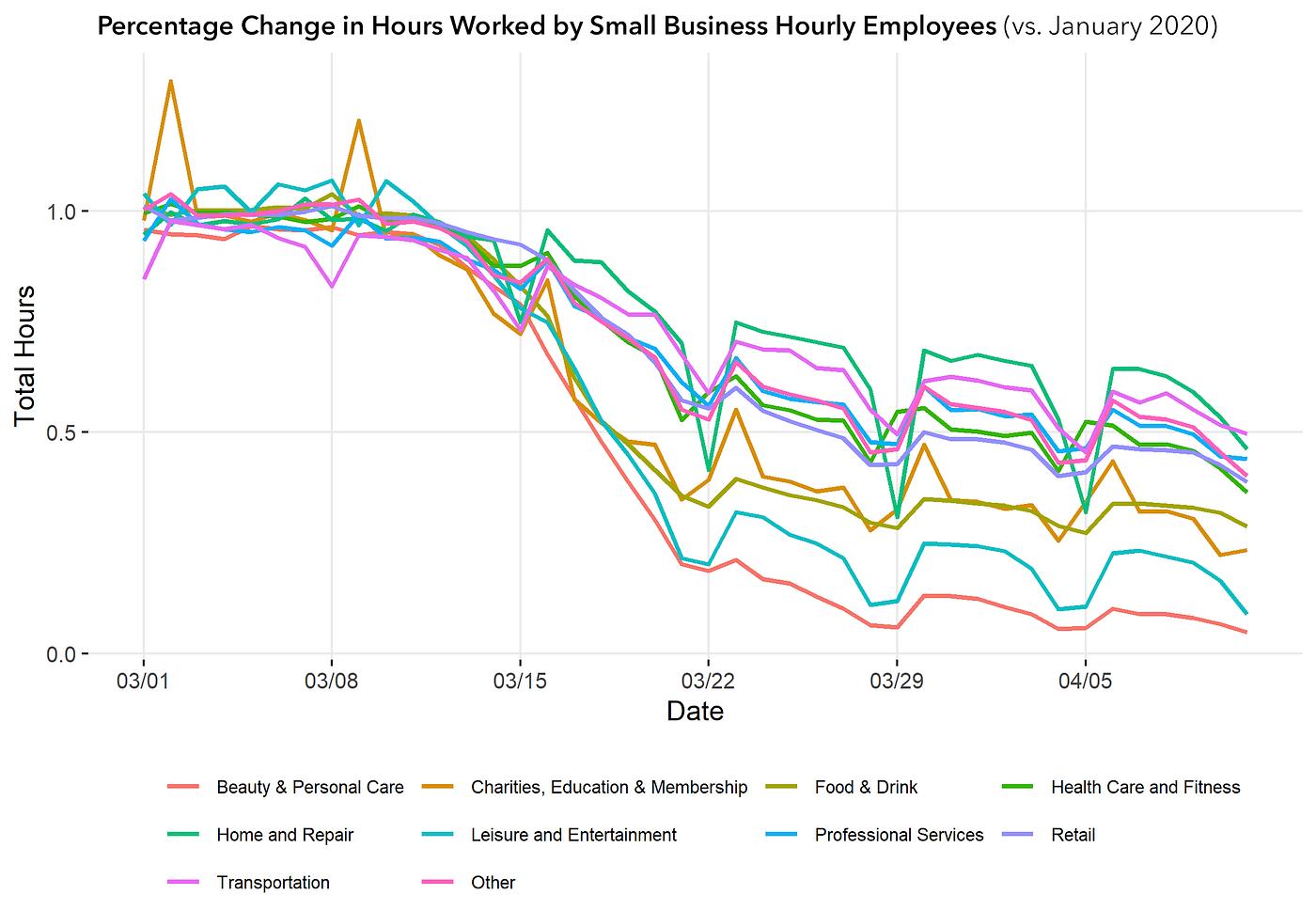

The lockdown has profoundly impacted hourly-wage workers, the most vulnerable workers in our economy. An analysis of timecard data from Homebase by researchers at the University of Chicago’s Rustandy Center for Social Sector Innovation has found that hourly workers in all sectors have seen significant declines in available work, with beauty, personal care, leisure, and entertainment nearing zero.

The good news is that there are ways to get more of the economy back on line while we continue to fight to flatten the COVID-19 curve.

Some commentators have propagated a dichotomy in which we can only improve public health through a total shutdown of the economy, and we can only improve the economy—in the near term—by sacrificing public health. This dichotomy is false. New technologies and emerging evidence regarding the epidemiology of COVID-19 will enable Americans to adopt a new strategy which can restore much of the U.S. economy without overly endangering public health.

Some commentators have propagated a dichotomy in which we can only improve public health through a total shutdown of the economy, and we can only improve the economy — in the near term — by sacrificing public health. This dichotomy is false.

Healthy Americans under 65 face lower mortality risks

While people of all ages have succumbed to COVID-19, there is considerable preliminary evidence that infection by SARS-CoV-2 is especially lethal in the elderly, especially in those who have preexisting conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure, diabetes, obesity, kidney failure, and immunodeficiency. Those between the ages of 40 and 65 appear to also be at risk if they have preexisting conditions.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the risk of death from COVID-19 is far greater in the elderly than it is for younger individuals. As of May 8, the CDC tallies 329 deaths associated with COVID-19 among Americans below the age of 35, and only 9 deaths among those below the age of 15. By contrast, there have been 29,661 deaths associated with COVID-19 among those over 65: 79 percent of the U.S. total.

The CDC counts are lower than other official counts due to different reporting criteria. Adjusting for the probability that we reach 120,000 deaths in the U.S., the odds of death for someone under age 35 are roughly 7 per million, or 1 per 140,000.

The risk of death from COVID-19 is far higher in the elderly than in younger Americans. According to datafrom the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, as of July 29, 2020, those older than 65 are 25 times as likely to die of COVID-19 than those aged 25 to 54. Note that not all COVID-19 deaths reported elsewhere are counted by CDC, and that not all CDC-counted deaths were caused by COVID-19; some of these individuals died from other causes, but tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. If we assume that there will be 200,000 total deaths from COVID-19 in the U.S., the odds of an individual under 25 dying from COVID-19 are around 2.5 per million, or 1 in 385,000. (Graphic: A. Roy / FREOPP)

This pattern has been found consistently all over the world, and suggests that we can do more than we are doing right now to bring low-risk populations back to work: in particular, healthy people of working age. It should soon be possible to study carefully the attributes of higher-risk patients on dimensions other than age and health status, in order to increase the number of people who can safely work. For example, there appears to be evidence that men are more at risk than women, and over time, we may find that certain genetic profiles confer higher or lower risk.

To be clear, this is not to say that there is no risk to younger individuals from COVID-19, but rather to suggest that the human benefits of reopening the economy with younger individuals is likely worth that risk. An April 9 survey by Data for Progress found that 52 percent of American voters under 45 have “already lost their job, been furloughed, placed on temporary leave, or had [their] hours reduced.” While the elderly are disproportionately affected by the COVID-19 disease, the non-elderly have been disproportionately affected by the economic consequences of our policy response.

Controlling the spread of COVID-19

In combination with targeted quarantines of infected individuals, “contact tracing,” a long-standing public health technique, can help us slow the spread of COVID-19 while we still have limited testing capacity.

Contact tracing involves interviewing a known infected patient; identifying all of the people whom that patient has been in contact with; alerting those individuals that they may be at risk; and then testing, treating, and/or isolating these other at-risk individuals.

Asian countries like Singapore, Taiwan, and South Korea have substantially upgraded contact tracing by incorporating geolocation data from patients’ Bluetooth and/or GPS-enabled smartphones.

On April 10, Apple and Google announced that they had agreed to collaborate on “application programming interfaces (APIs) and operating system-level technology to assist in enabling contact tracing” and also a “Bluetooth-based contact tracing platform.” The Apple-Google effort could dramatically accelerate the ability of third parties, including public health authorities, to develop smartphone apps that can establish nationwide contact tracing.

It will be important to ensure that contact tracing adheres to U.S. privacy laws, including the California Consumer Privacy Act. The American Civil Liberties Union has described the Apple-Google effort as one “that appears to mitigate the worst privacy and centralization risks,” because of its Bluetooth-based approach. But while Bluetooth is a superior approach from a privacy standpoint, it is not completely accurate, because two individuals could be defined as “connected” via Bluetooth even if they are in separate rooms without any contact with each other.

We estimate that if 50 percent of the population uses these apps, we can achieve sufficiently robust contact tracing. We believe that the government should create powerful incentives to make it very easy for infected contacts to participate and self-quarantine, by providing income relief and accommodation when necessary in order to break the chain of transmission. Federal and state authorities can supplement technology-based contact tracing by also increasing funding for the traditional personal interview-based approach.

Effective contact tracing may only require a modest ramp-up of testing from current levels. An April 7 paper published by Mark McClellan and colleagues at the Duke Margolis Center for Health Policy estimates preliminarily that “a national capacity of at least 750,000 tests per week [will] allow for isolation and contact tracing.” 750,000 per week is only slightly above mid-April U.S. levels of 100,000 per day, although present testing capacity relies too heavily on antibody assays instead of RT-PCR.

A new strategy for reopening the economy

This combination of factors—(1) the significant possibility of a pessimistic scenario, in which the spread of the virus cannot be completely contained in the near term; (2) the heavy skew of poor health outcomes and death from COVID-19 disease toward the elderly and those with chronic disease; and (3) new tools for contact tracing and quarantines—lead us to propose a new strategy for bringing Americans back to work and restoring as much of the U.S. economy as possible:

- Reopen pre-K and K-12 schools. While COVID-19 hospitalization and death rates among school-aged children are greater than zero, they are sufficiently low to justify the reopening of schools, preschools, and child care centers. Students who live with high-risk individuals, such as the elderly and those with chronic disease, and/or are in regular close contact with high-risk individuals, should remain at home, as should high-risk teachers and staff. Schools should administer deep-cleaning techniques on a daily basis in order to minimize the spread of SARS-CoV-2, and adopt other public health best practices, such as routine hand-washing. Schools should consider grouping cohorts of students together, and reorganizing staff so as to reduce contacts per student per day. Reopening schools will help us avoid widening educational inequities in the U.S., and enable more parents of school-aged children to work productively. Public primary and secondary schools should consider making up for lost time by completing the spring semester in the summer months. California Gov. Gavin Newsom, for example, is considering starting the 2020–21 school year in July. For children who must remain at home, due to their relationship with high-risk individuals, state and local governments should ensure access to high-quality learning options, including reliable internet access and options for virtual instruction, such as the “inverted classroom” model in which lectures are recorded, and teacher time is invested in interactive tutoring. In particular, states should take the lead in planning virtual curricula for all K-12 students in their districts who need to stay home. Schools should also establish continuity plans in case the 2020–21 school year is disrupted by a prolonged outbreak.

Reopening America’s Schools and Colleges During COVID-19

To reduce disparities, we must reopen schools, colleges, and child care, and enable microschool ‘pods’ for those who’d…

- Lift stay-at-home orders for most non-elderly individuals. Healthy individuals under the age of 65 who are not in regular contact with high-risk individuals should be allowed by state governments to return to work, even if they work at “non-essential” businesses. Individuals between the ages of 40 and 65 should consider continuing to stay home if they have any underlying conditions that make them more susceptible to death or hospitalization with COVID-19, such as cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure, diabetes, severe asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), kidney failure, severe liver disease, immunodeficiency, and malignant cancer. It is worth noting that a large percentage of the over-40 population has one of these conditions, and so it will be essential to monitor COVID-19 cases over time for evidence that helps us narrow the categories of risk, and also evidence regarding the relationship between positive antibody tests and immunity. State officials should strongly encourage individuals returning to work to download and deploy contact tracing apps that meet U.S. privacy standards and have the potential for sufficiently widespread use.

- Reopen safe, but “non-essential” businesses. For example, car washes may not be “essential” in the way that hospitals are, but drive-through car washes require no social interaction and do not facilitate person-to-person viral transmission. States and localities should be responsive to businesses that can operate safely in a pandemic environment, regardless of whether or not their workforce includes elderly or at-risk populations.

- Focus on the risk in nursing homes and assisted living facilities. As noted above, two-fifths of all U.S. COVID-19 deaths have taken place in nursing homes or assisted living facilities. Nursing homes, which house elderly individuals who require 24/7 medical supervision, are especially vulnerable to COVID-19. Inattention to the impact of COVID-19 in nursing homes has led to tragic outcomes in the U.S. and elsewhere. States should immediately restrict visits to nursing homes by relatives and friends, and nursing home operators should do everything possible to ensure that nursing home workers are assigned to a single facility and tested as frequently as possible by RT-PCR for active infection.

- Rescind mandatory discharges of COVID-19 patients to nursing homes. In March, the New York State Department of Health issued a directive forcing nursing homes to accept patients who had been discharged from hospitals after being infected with SARS-CoV-2. This mandate exacerbated the outbreak of COVID-19 in New York and neighboring states. New Jersey and Michigan have imposed similar mandates. Such mandates should be rescinded, and replaced with methods that help seniors recover without putting nursing home residents at risk.

- Contract with empty hotels to house COVID-19 patients. State governments should contract with hotel owners to house coronavirus-infected patients who have no alternative to living at home. Quarantined housing can especially help those who live or work with someone in a nursing home or other high-risk cohort.

- Prioritize testing in nursing homes, assisted living facilities, and other congregate settings with high-risk populations. As testing ramps up, it will be essential to ensure that people working or living in high-risk settings have access to FDA-approved tests. These include nursing home workers and residents; health care workers; hospital patients; and those working or living in high-risk congregate settings such as nursing homes, rehabilitation facilities, jails, and prisons. In addition, the FDA should do everything it can to make home-based RT-PCR testing feasible, so that we can quickly diagnose acute infections, minimizing the number of exposed contacts.

- Ensure accurate reporting of nursing home fatalities. A number of states are failing to report COVID-19 fatalities in nursing homes and assisted living facilities. Federal authorities should require such disclosure.

- Continue to build up ICU, personal protective equipment (PPE), and N95 mask capacity. The U.S. should continue to build up its capacity to treat patients with acute respiratory syndromes, in order to ensure that a second wave of infections does not destabilize our health care infrastructure. Supplying PPE is important not only for first responders but even more so for nursing homes and assisted living facilities, as failure to prevent outbreak in congregate settings will lead to a greater number of hospitalizations.

- Incentivize employers to deploy RT-PCR testing at work. Congress should offer a $300-per-test tax credit — roughly equivalent to the cost of an RT-PCR test — for businesses that administer RT-PCR tests to their workers, and grant employers safe harbor from liability for administering these tests. Workplace testing will accelerate re-employment, and also increase consumer confidence in retail businesses that institute universal testing. A fixed-dollar tax credit will incentivize employers to shop for the most cost-effective testing platform, and incentive price competition among test suppliers.

- Incentivize consumers to use contact tracing apps. Similarly, Congress could offer a $50 tax credit to consumers who download a certified contact tracing app that meets agreed-upon standards of privacy and robustness.

- Continue to prohibit large group gatherings. To reduce risk of the U.S. relapsing into rampant transmission, states should continue to prohibit large group gatherings like sporting events, concerts, conventions, and theme parks. High risk locations like bars, nightclubs, and gyms should remain closed until infection reproduction rates, as measured by R₀, decline below 1. States and localities should allow restaurants to reopen, but with seating arrangements that enable physical distancing, and actively estimate R₀ in localities and counties.

- Carefully reopen passenger air and Amtrak travel. In order to reduce the risk of spreading the novel coronavirus to other individuals on passenger flights and Amtrak trains, Amtrak and all airlines should be required to keep middle seats unoccupied, so long as they are receiving aid from Congress to maintain their operations. Airlines should supply passengers with masks and alcohol wipes, and deep-clean each plane after each flight, as some airlines are already doing. Those wishing to engage in air and Amtrak travel should be required to participate in a certified contact tracing app, and airlines should test their flight crew as often as possible—at least once or twice weekly—by RT-PCR to confirm the absence of active infections. Once scaled-up testing is feasible, passengers should be required to demonstrate at check-in that they have tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 with an FDA-approved RT-PCR test and attest that they have not had any symptoms within the last two weeks. If antibodies are ultimately shown to be protective, proof of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies could also suffice for boarding. Localities could deploy these measures for subways, buses, and commuter rail, where feasible. Since carriers will have an economic incentive to increase their passenger loads, Congress should appropriate funds to help them facilitate passenger testing. As a supplemental testing measure, the Transportation Security Administration should work with airports to ensure that airport scanners are configured to detect passengers with unusually high temperatures, as fever can be a sign of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

- Grant safe harbor to states that restrict interstate travel. It may become necessary for state governments to restrict Americans from entering their jurisdictions by car from a bordering state where a COVID-19 outbreak has occurred. For example, on March 29, in response to a COVID-19 outbreak in New Orleans, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott signed an executive order requiring those entering Texas by road from Louisiana to enter quarantine for 14 days while in Texas. Under the U.S. Constitution, regulation of interstate commerce is the domain of the federal government; hence, it may be worthwhile for Congress to grant a temporary safe harbor to states that restrict travel due to COVID-19, so as to ensure that such measures are not overturned in litigation.

- Minimize non-essential inpatient admissions. There is considerable evidence, compiled here by Jonathan Tepper, that nosocomial infections—those spreading within a hospital—are a significant contributor to the COVID-19 outbreak. Federal and state authorities should work with clinicians and acute care facilities to ensure that as many patients as possible are cared for through virtual visits and sent to outpatient facilities.

- Develop community testing strategies. As the Santa Clara serology study demonstrated, it is essential to understand the true prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection rates in the community, so as to understand the true danger of infection. Public health officials should build on strategic plans for broad-based RT-PCR and antibody testing so as to fully understand seroprevalence rates. Such testing might involve community drive-in sites, workplace sites, or physician offices and pharmacies. Insurers and physicians should work together to ensure that every patient that goes in for an annual physical exam is tested for coronaviral RNA and antibodies, with no cost-sharing for the patient.

- Incentivize states to grant reciprocity to physicians with out-of-state licenses, and liberalize scope-of-practice regulations. Each U.S. state has its own system for licensing physicians, which creates artificial barriers to the movement of physicians to areas of need: a barrier that becomes a crisis during pandemics. Congress should reserve some portion of federal health care aid to states that enact laws that enable any physician licensed in another U.S. state to practice under that license within its jurisdiction. Removing these barriers should be simple; health care startup Merit, for example, has created a verified identity platform that can enable cross-state reciprocal licensure. Similarly, Congress should reward states that allow nurse practitioners, physician assistants, nurse anesthetists, and other physician extenders to practice to the top of their licenses without supervision from a physician. Today, many states have “scope of practice” laws that arbitrarily restrict these health care professionals from performing services they are well-trained to do.

A new multi-risk susceptible-infected-recovered model (MR-SIR) developed by four MIT economists finds that “semi-targeted policies that simply apply a strict lockdown on the oldest group can achieve the majority of the gains from fully-targeted policies,” while roughly halving the economic damage. “The reason is that, once the most vulnerable group is protected, the other groups can be reincorporated into the economy more quickly.” And low-density localities with plenty of excess ICU capacity may find that even targeted lockdowns need not be strict, so long at-risk individuals continue to practice basic safety measures such as hand washing and physical distancing.

Repairing the damage already done

Central to the new strategy we are proposing is the fact that the lockdown has caused staggering economic and human damage in just a short time. The stimulus bills passed by Congress may achieve some good, especially those elements that help small businesses pay their workers during the stay-at-home period. But others are poorly targeted, such as the indiscriminate $1,200 checks being sent to most Americans, regardless of COVID-related need.

Still others—like costly employer mandates that make it even more difficult to retain workers—are actually counterproductive. For example, on March 13, Congress passed the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, which contains a poorly-designed requirement that employers offer workers 12 weeks of paid sick leave, partially offset by a complex and cumbersome tax credit on the back end. Most large businesses already offer paid sick leave, but smaller businesses with limited cash cushions will face additional pressure under the mandate to lay off workers and close their doors.

Policymakers in Washington are actively considering additional stimulus bills, and state governments continue to look for ways to aid their communities. These additional vehicles could be used to consider the below policies:

- Health reinsurance to fund the cost of care for the sick. Reinsurance, which works like an invisible high risk pool, can be used to directly fund the costs of caring for sick individuals such as those with COVID-19. Congress should fund a reinsurance pool of $20 billion per year for the individual insurance market, so that those who have lost their jobs have the opportunity to find affordable premiums in these alternative markets.

- Reduce seniors’ out-of-pocket exposure to prescription drug costs. The Senate Finance Committee has reported out a package of reforms that would cap out-of-pocket costs in the Medicare prescription drug benefit, while also reducing overall Medicare spending by $100 billion over 10 years. These savings would help offset increased spending on reinsurance and other programs.

- Provide additional support to high-risk populations. Unless we successfully develop a vaccine or population-level immunity, people over 65 and the other high-risk populations discussed above will not be able to work and participate fully in society. Congress should provide income relief for non-retired individuals who cannot safely work, and authorities should facilitate social support through mechanisms like touchless food delivery, telemedicine, and virtual mental health care.

- Invest in health care data exchanges among—and within—states. COVID-19 has revealed enormous gaps in health care information, hindering our ability to respond effectively to the pandemic. Most states have built homegrown spreadsheets to track hospital occupancy, resources like ventilators and PPE, and population-level infection and diagnostic data. These spreadsheets should be converted into lasting connections, APIs, and data feeds, so that when future outbreaks occur, the health system will be far more responsive and adaptable. In 2010, the HITECH Act created requirements for electronic health records to be able to exchange hospital occupancy data as well as funding to create state information exchanges, but many states still lack this connectivity.

- Large states with major metropolises should build independent emergency medical stockpiles. Congress never intended for the Strategic National Stockpile (SNS) to address a prolonged nationwide pandemic. Instead, the SNS was designed to serve as a resource for more regionalized bioterror attacks and natural disasters, and as a “fallback” once private sector and state supplies were exhausted. Alarmingly, nearly 90 percent of the SNS’s personal protective equipment (PPE) became depleted by early April. States with large urban centers, such as New York, Florida, California, Pennsylvania, and Illinois, should consider building independent stockpiles of ventilators and PPE based on their own needs.

- Re-envision management of the Strategic National Stockpile and federal contracts for emergency preparedness. Reporting from ProPublica and the New York Times revealed how myriad missteps and red tape led to a national shortage of ventilators. In 2006, federal officials sought to procure 70,000 private-sector ventilators over ten years; in March 2020, only 12,700 were available for distribution. It will be important for the executive branch to objectively assess these bureaucratic barriers, and facilitate interagency cooperation regarding emergency preparedness contracts.

- Accelerate highway infrastructure projects. States and localities should take advantage of reduced vehicle traffic to accelerate highway infrastructure projects. Acceleration could provide a near-term economic stimulus, by employing more people, and also the mid-term recovery, by reducing traffic congestion.

- Provide resources and support to schools and education providers that open during the summer. Disparities in educational outcomes are at risk of widening during this period of school closure, because low-income parents lack the resources to provide educational opportunities to their children outside of school. Congress and state governments can help financially support schools and education service providers that elect to remain open in the summer to make up for lost time, or to otherwise ensure that children have equal access to high-quality learning options outside of school where needed. If teacher union contracts prevent schools from opening during the summer months, federal and/or state COVID-19 relief funding could be applied to Education Savings Accounts that families could use to purchase online learning services.

- Address the potential humanitarian crisis in America’s jails and prisons. As Jonathan Blanks has described, correctional facilities were not built to enable physical distancing. Congress should provide additional funding to ensure that federal, state, and local facilities have the means to test inmates and workers for the novel coronavirus; quarantine those who test positive; and consider early parole or release for SARS-CoV-2-negative individuals who meet criteria for non-violence and risk.

Who benefits from partially reopening schools and the economy?

Our plan is designed to maximize America’s ability to reopen our economy while protecting public health. But the path we recommend has important limitations.

For example, our proposal to reopen schools to children who do not live with elderly or at-risk individuals means that some children will have to stay home. Chronic diseases are more highly prevalent among low-income populations and African-Americans. On the flip side, today, there are single mothers who cannot work because it would force them to leave their children at home, alone.

We believe that the benefits to those children and parents outweigh the disadvantages of a partial reopening of schools. However, it is important for states and localities to do everything they can to facilitate virtual learning for those who remain home.

A partial reopening of the workplace may involve similar temporary disparities. A broad-based program of workplace testing can help mitigate this problem. And, again, continuing the economic lockdown with no effort at reopening will have even worse effects on disadvantaged communities and low-income households.

There is ample evidence that significant increases in unemployment lead to an increase in death. A 1 percentage-point rise in the U.S. unemployment rate is associated with a 6% increase in the chance of dying within the next year. In heart failure patients alone, unemployment is associated with a 50% higher risk of death.

These economic effects are separate from the direct effects on the health care system of neglecting or avoiding needed care. We do not yet know how many Americans have foregone health care unrelated to COVID-19, but the preliminary evidence is significant. Organ donations and transplantations have decreased precipitously, harming those with end-stage liver disease. In North Carolina, far fewer people are visiting emergency rooms, which may be an indication that ordinary conditions like heart attacks are not being adequately treated. Disruptions in cancer care may significantly increase mortality. Many clinical trials for new treatments have ground to a halt. To date, no one has attempted a systematic analysis of these costs.

Comparing the relative risk of death from COVID-19 vs. influenza or pneumonia. Estimating relative risk is highly dependent upon the ultimate lethality of COVID-19, which is unknown at this time. Nonetheless, a clear pattern emerges from what we know, in which those under aged 15 are at the lowest risk of death from COVID-19, relative to influenza or pneumonia. COVID-19 data as of July 15, 2020. (Source: National Center for Health Statistics; CDC; A. Roy / FREOPP)

Learn from history, but rely on new evidence

Much of the traditional paradigm for managing pandemics comes from our historical experiences, especially the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic. But COVID-19 is not the flu, and those whose policy recommendations are primarily based on the 1918 experience will ignore important options for reopening the economy.

SARS-CoV-2 may not as easily lend itself to vaccine production as influenza does. And, relative to the flu, the COVID-19 disease far more heavily impacts the elderly and those with chronic diseases. The primary reason for the lockdown was a fear that COVID-19 would overwhelm U.S. hospital capacity; instead, today, most U.S. hospitals are seeing unusually low utilization.

In other words, while we must learn from our history, we must not be wedded to it. Instead, we must focus on the specific biology of the virus at hand, and the specific evidence of the disease at hand. If we do these things, we will find that we have better options to improve public health and reopen the economy than many have believed.

About the authors

, Ph.D., is a member of FREOPP’s Board of Directors. He is the David and Diane Steffy Research Fellow at the Hoover Institution, and Director of Domestic Policy Studies and Lecturer in Stanford’s Public Policy Program. In 2012, he served as Mitt Romney’s policy director, and was a senior adviser to Marco Rubio’s 2016 presidential campaign. During the George W. Bush administration, Chen served as a senior official at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

, M.D., is a member of FREOPP’s Board of Advisors. He is a partner at Venrock, a venture capital firm, an Adjunct Professor at the Stanford University School of Medicine, and a Senior Fellow at the Schaeffer Center for Healthcare Policy at USC. From 2009 to 2010, he served on President Obama’s National Economic Council as Special Assistant to the President for Healthcare and Economic Policy. Prior to that, he was a partner at McKinsey & Company.

is the co-founder and President of FREOPP. He is also the Policy Editor at Forbes and a Senior Advisor to the Bipartisan Policy Center. He has advised three presidential candidates on public policy, including Mitt Romney, Rick Perry, and Marco Rubio. Prior to these roles, Roy worked as an institutional investor in health care companies, at Bain Capital and J.P. Morgan, among other firms.

, M.D., is Professor and Chair of the Department of Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. He is past president of the Society of Hospital Medicine, and past chair of the American Board of Internal Medicine. In 2015, Modern Healthcare named him the most influential physician-executive in the United States. In 2004, he received the John M. Eisenberg Award, the nation’s top honor in patient safety and quality. He has served on the healthcare advisory boards of several companies, including Google and Teladoc.

is a Research Fellow at FREOPP in health care reform.

is a Visiting Fellow at FREOPP in education reform.

About FREOPP

The Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity (FREOPP) is a non-profit, non-partisan think tank focused on expanding economic opportunity to those who least have it, using the tools of individual liberty, free enterprise, and technological innovation. All research conducted by FREOPP considers the impact of public policies and proposed reforms on those with incomes or wealth below the U.S. median. For more information, please visit our Mission page.

FREOPP does not take institutional positions on any specific policy issues, and the views expressed in this paper are solely those of the authors.

Revision history

- April 20: Added minor edits and revisions; added Robert Wachter as a co-author; expanded sections on testing and treatment; added discussion of anecdotal remdesivir data; added CDC data on mortality by age bracket, and a discussion of the Santa Clara County and Los Angeles County serology studies; expanded discussion of air & train travel and public transit; deleted recommendation to establish temporary hospitals; added section on inequality; added discussion of hospital capacity.

- April 26: Removed discussion of Santa Clara County and Los Angeles County serology studies; revised and expanded proposal to re-open passenger air travel and Amtrak to include subways, buses, and commuter rail.

- April 27: Added supplemental content from the Wall Street Journal and American Wonk; incorporated latest data on remdesivir and Kevzara.

- April 28: Added figure from the COVID Tracking Project on the number of daily tests completed in the U.S.; added discussion of California’s consideration of an expanded 2020–21 school year.

- May 5: Removed recommendation for supplementing Medicare Advantage reinsurance funds; added discussion of NBER paper on targeted lockdowns by Daron Acemoglu et al.; updated discussion of remdesivir to include NIAID study and EUA; removed asthma and COPD as risk factors associated with COVID-19 morbidity and mortality (cardiovascular risk factors appear to be more important than pulmonary ones); added analysis of Homebase hourly wage data.

- May 11: Added data on COVID-19 fatalities in nursing homes and personal care homes.

- May 12: Updated chart and discussion of COVID-19 fatalities by age. Reorganized and expanded discussion of nursing and personal care homes.

- May 13: Added new chart illustrating age distribution of COVID-19 fatalities by age assuming that total U.S. deaths equal 120,000. Added note that South Korean “reinfections” appear to have been false positives. Added NBER report on 100,000 small business closures and issues with the CARES Act and Paycheck Protection Program.

- May 18: Updated COVID-19 fatality age distribution charts; added chart on age-related relative risk of death from COVID-19 vs. influenza or pneumonia.

- July 30: Updated COVID-19 fatality age distribution charts.

- August 24: Added a discussion of the significance of a reported case of a reinfected patient in Hong Kong.