The Fair Care Act of 2020: Market-Based Universal Coverage

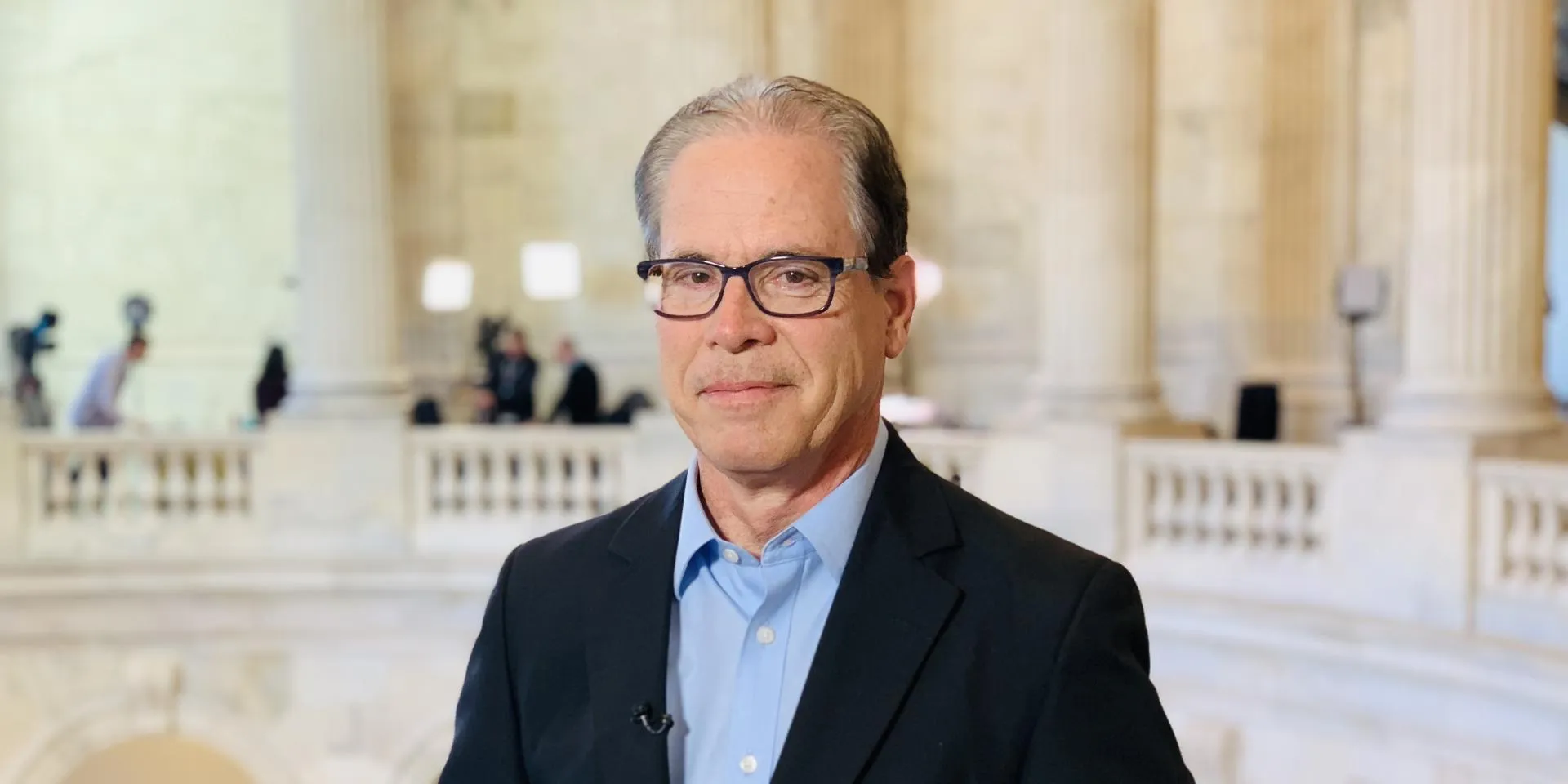

Sen. Mike Braun (Ind.) co-sponsored the Fair Care Act of 2020. (Photo: Sen. Mike Braun)

InWashington, it is commonly thought that the debate about health care reform is hopelessly partisan and ideologically intractable. But a group of congressmen, including Sen. Mike Braun (Ind.), Rep. Bruce Westerman (Ark.), Rep. Jim Banks (Ind.), Rep. Denver Riggleman (Va.), and Rep. Lloyd Smucker (Pa.), have produced an ambitious and far-reaching health reform bill, the Fair Care Act of 2020, that could provide the basis for bridging these conventional divides.

The Fair Care Act, says Westerman, “takes more than 75 bipartisan provisions and many other ideas and brings them together into a comprehensive bill, with [the] two goals of increasing those covered by health insurance and lowering the overall cost of health care.”

Aside from the policy merits of expanding coverage and decreasing health spending, such a framework is the only one that can conceivably receive both Democratic and Republican support in Congress. Democrats will not vote for a broad health reform bill that reduces the number of Americans with health insurance, and Republicans will not vote for one that increases federal spending.

The affordability of health insurance is not merely an important issue for the 27 million legal U.S. residents who lack coverage. It is also a critical issue for tens of millions more who have insurance, but for whom rising premiums and out-of-pocket costs are depressing wage growth and threatening living standards.

Furthermore, the long-term solvency of the United States hinges on our ability to reduce the cost of health care, and thereby growth in public spending on health care. In the FREOPP 2021 World Index of Healthcare Innovation, the U.S. ranked 29th out of 31 high-income countries on the fiscal sustainability of its health care system, ahead only of France and Japan.

How the Fair Care Act reforms U.S. health care

The Fair Care Act seeks to address these issues in four ways.

Universal coverage. The bill would provide meaningful financial assistance to all remaining uninsured individuals who are legally present in the U.S., especially those below the Federal Poverty Level. The bill also takes significant steps to reduce the underlying cost of health insurance, by reforming insurance regulations, supporting innovative technologies, and increasing price competition for hospital care and prescription drugs.

Personalized insurance. The bill would dramatically expand the ability of Americans to choose their own coverage, instead of having it purchased for them by the government or their employers. We estimate that over 100 million Americans would enjoy more choices in coverage under the Fair Care Act. Those who directly buy coverage would enjoy more choice and competition on the individual insurance marketplaces. Many able-bodied adults on Medicaid would also gain the opportunity to choose their own coverage on these reformed marketplaces, improving access to care. And seniors gain additional coverage choices through a more competitive Medicare Advantage program. The bill transforms the value and utility of medical savings accounts such as HSAs, FSAs, and HRAs, by consolidating them into unified tax-free Medisave accounts that can be used for the purchase of health insurance, direct primary care, and other medical services.

Fairness to taxpayers. Through Medicare and the tax code, middle- and low-income U.S. taxpayers help provide tens of billions of health care subsidies to those who do not need it — large multinational corporations and the wealthiest Americans — while providing limited relief to the working poor and middle class. The Fair Care Act moves toward a system in which vulnerable populations are the focus of taxpayer assistance.

Innovation and competition for patients. The Fair Care Act creates a new accelerated pathway for the review and approval of innovative medicines. It establishes full authorization for the use of telemedicine in federal programs. The bill establishes universal transparency for the prices paid by insurers to providers, and also for the 100 most “shoppable” health care services. And, as noted above, the bill substantially increases the role of competition in reducing prices and increasing the quality of hospital care and prescription drugs.

We estimate that, by 2030, the Fair Care Act would reduce the number of uninsured legal U.S. residents by 35 percent, from 26 million under the Congressional Budget Office’s 2030 baseline to 17 million under the Fair Care Act. Importantly, all of the remaining uninsured individuals would be those who choose to remain uninsured despite the availability of considerable financial assistance to buy coverage. Excluded from these calculations are undocumented immigrants, who are ineligible for subsidies to purchase health insurance under current law and also under the Fair Care Act.

The composition of the uninsured varies widely by income. Among those with incomes below 150% of the Federal Poverty Level — $19,140 for a childless adult in 2020 — the two largest groups of uninsured individuals are people living in states that did not expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, and illegal immigrants. Nonetheless, 60% of those in this income group who are lawfully present in the U.S. are already eligible for subsidies in some form. All legal U.S. residents between 150% and 400% of FPL are eligible for subsidies, while 59% of the uninsured above 400% of FPL have turned down a subsidized offer of employer-based coverage. (Graphic: A. Roy / FREOPP)

Who, exactly, is uninsured in America?

According to the Congressional Budget Office, 31.5 million individuals living in the U.S. in 2021 will not have health insurance. These individuals, however, are uninsured for different reasons:

- Subsidy-eligible individuals who decline coverage. Among those lawfully present, three-fourths of the uninsured — 21 million — are already eligible for financial assistance to obtain coverage, either through their employers or through other federal programs, such as Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and the Affordable Care Act (ACA). In the case of the ACA, for many people, dramatic rises in insurance premiums offset the amount of premium assistance the law offered them.

- Citizens & legal residents ineligible for subsidies. 3.9 million U.S. legal residents have incomes below the Federal Poverty Level (in 2020, $12,760 for a childless adult and $26,200 for a family of four), but live in states that have not expanded Medicaid, and are not otherwise eligible for Medicaid under current law: the so-called “Medicaid coverage gap.” 2.9 million uninsured individuals have incomes above 400% of the Federal Poverty Level ($51,040 for a childless adult and $104,800 for a family of four), and are therefore ineligible for subsidies on the ACA marketplaces, but have no alternative offer of affordable employer-sponsored coverage.

- Undocumented immigrants. Individuals not lawfully present in the U.S. comprise 4.3 million, or 14% of the uninsured population. These individuals are not eligible for subsidies under existing federal programs, though former Vice President Joe Biden has proposed including them. (More than 6 million illegal immigrants do have subsidized coverage, some through their employers or the employers of a family member.)The donut charts above illustrate this problem in greater detail. All legal residents with incomes between 150% and 400% of the Federal Poverty Level are currently eligible for subsidized coverage, either through their employers (dark blue) or means-tested federal programs (orange). Those ineligible for subsidies include those living in non-Medicaid expansion states or with incomes above 400% FPL (medium blue), and undocumented immigrants (light grey).

Covering the remaining uninsured

The Fair Care Act substantially reduces the uninsured population in each legally resident group:

- Reducing the underlying cost of health care. Through a broad array of measures, the Fair Care Act significantly reduces the underlying cost of health care, especially that of hospital care and prescription drugs, thereby increasing the affordability of both employer-sponsored and individually-purchased health insurance.

- Reforming the ACA marketplaces. Fundamental design flaws in the Affordable Care Act have made individually-purchased insurance unaffordable for millions of individuals. For many, premiums have more than tripled relative to the pre-ACA market. The Fair Care Act contains a series of reforms that reduce premiums in the individual marketplaces by more than 30%, and expand the range of affordable choices available to marketplace enrollees.

- Filling the coverage gaps. The Fair Care Act establishes a market-based alternative to the ACA Medicaid expansion, by expanding eligibility for advance premium tax credits to those below 100% FPL. States become eligible for this option if they also transition their pre-ACA Medicaid programs into a per-capita allotment model. The Fair Care Act also extends tax credits to eligible households with incomes between 400% and 600% FPL. This additional assistance is funded by reducing — or eliminating — federal health care subsidies for the wealthy.

As shown in the graphs below, nearly all participants in the Fair Care Act’s insurance marketplaces would obtain premiums net of subsidies that are equal to or lower than prices found under the Affordable Care Act. Net premiums would be substantially lower for those below the Federal Poverty level, and also for those above 400% of FPL. Among those with incomes between 133% and 400%, net premiums would remain largely the same, due though younger individuals would see significantly lower premiums, especially above 300% FPL.

The Fair Care Act would reduce underlying premiums for 27-year-olds by 46%. The FCA reduces premiums for all participants in the nongroup health insurance marketplaces, through economies of scale, establishing a reinsurance program, and increasing enrollment of young people. We estimate that this combination of effects reduces premiums by 30%. On top of that, young people benefit from age-adjusted premium assistance, and widened “age bands” that enable younger enrollees to gain greater price discounts. (Graphic: A. Roy / FREOPP)

The Fair Care Act would reduce underlying premiums for 40-year-olds by 30%. The FCA reduces premiums for all participants in the nongroup health insurance marketplaces, through economies of scale, establishing a reinsurance program, and increasing enrollment of young people. We estimate that this combination of effects reduces premiums by 30%. Among subsidized enrollees, 40-year-olds with incomes above $40,000 benefit from reduced premiums. Those with incomes below the Federal Poverty Level would also gain premium assistance under the Fair Care Act, of particular importance in states that have not expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act. (Graphic: A. Roy / FREOPP)

The Fair Care Act would reduce underlying premiums for 60-year-olds by 9%. The FCA reduces premiums for all participants in the nongroup health insurance marketplaces, through economies of scale, establishing a reinsurance program, and increasing enrollment of young people. We estimate that this combination of effects reduces premiums by 30%. The effect on underlying premiums is smaller among 60-year-olds, because the Fair Care Act allows for 5:1 “age bands” that enable greater discounts for younger enrollees. 60-year-olds especially benefit from the Fair Care Act’s extension of premium assistance to people with incomes between 400% and 600% of the Federal Poverty Level: between $51,040 and $76,560 in annual income in 2021. (Graphic: A. Roy / FREOPP)

The Fair Care Act would reduce underlying premiums for families by 30%. The FCA reduces premiums for all participants in the nongroup health insurance marketplaces, through economies of scale, establishing a reinsurance program, and increasing enrollment of young people. We estimate that this combination of effects reduces premiums by 30%. Families below the poverty line would gain full premium assistance, of particular importance in states that have not expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act. Families with incomes between 400% and 600% of the Federal Poverty Level — between $104,800 and $157,200 in annual income for a family of four — benefit from the Fair Care Act’s extension of premium assistance to 600% FPL. (Graphic: A. Roy / FREOPP)

Protecting people with pre-existing conditions

The Affordable Care Act’s best-known feature is its requirement that insurers offer coverage to those with pre-existing conditions, also known as guaranteed issue. What is less well understood is the fact that the ACA also made insurance less affordable for healthy uninsured people, by forcing them to pay higher premiums to offset the lower premiums paid by the sick: a feature known as community rating.

The Fair Care Act fixes this problem, and strengthens protections for those with pre-existing conditions, by maintaining guaranteed issue and community rating, but also adding in a reinsurance program—an integrated, invisible high-risk pool—that directly covers the cost of care for the sickest enrollees in the Fair Care Act’s marketplaces. This funding, in turn, lowers premiums for healthy enrollees, who no longer need to be overcharged to pay for the sick. Lower premiums for the healthy majority result in reduced need for premium subsidies, offsetting a significant portion of the cost of reinsurance. Based on Congressional Budget Office projections, we estimate that the Fair Care Act’s $20 billion per year reinsurance program would lower premiums by 25–30%, leading to a net reinsurance cost of less than $6 billion per year, after offsets are taken into account.

The Fair Care Act also makes health insurance more affordable for younger enrollees, by enabling them to obtain greater discounts on premiums and also to receive more premium assistance.

This combination of reforms—making insurance more attractive for the healthy and the young, through reinsurance and improved age adjustment—will strengthen the marketplaces’ risk pools, reducing premiums for all, including those with pre-existing conditions.

The Fair Care Act would extend guaranteed issue to Medigap plans: supplemental insurance plans purchased by Medicare enrollees to cover out-of-pocket expenses. Medigap plans are popular with seniors in the traditional Medicare program, which has no out-of-pocket limits; without Medigap, seniors in fee-for-service Medicare can face extremely high costs for serious illnesses or extended hospital stays. But because Medigap plans can refuse coverage for those with pre-existing conditions, their protections are incomplete. (Medicare Advantage plans, by contrast, have an out-of-pocket limit in 2020 of $6,700.)

These protections are designed to remain in place regardless of how the Supreme Court rules in California v. Texas, the 2020 case regarding the constitutionality of the ACA’s individual mandate.

Prior to the Affordable Care Act, most individual market enrollees preferred high-deductible plans. A majority of individual market enrollees in 2010 enrolled in Copper or Tin plans with an average actuarial value of 52% (i.e., the premium was expected to cover 52% of health care consumption, and out-of-pocket costs the other 48%). Plans with actuarial values below 60% were made illegal under the Affordable Care Act, depriving consumers of more affordable options. (Graphic: A. Roy / FREOPP)

Expanding health insurance choices for all Americans

The Fair Care Act would significantly improve the ability to choose their own health insurance plans, through several mechanisms:

- Individual insurance market reforms. As described above, the bill would significantly reduce premiums in the individual market and broaden the eligibility for tax credits to purchase coverage. The Fair Care Act also establishes Copper plans, based on a bill introduced in 2014 by Sens. Mark Begich (Alaska), Mark Warner (Va.), Heidi Heitkamp (N.D.), Tim Kaine (Va.), Mary Landrieu (La.), Angus King (Maine), and Joe Manchin (W.Va.), as a more affordable option for some consumers. Similarly, the Fair Care Act fully legalizes short-term limited-duration insurance (STLDI) plans, so as to create additional choices for those who cannot afford traditional coverage.

- Employer-sponsored insurance reform. Building on a Trump administration rule enabling employers to fund Health Reimbursement Arrangements (HRAs) for workers to purchase individual market coverage, the Fair Care Act empowers employers to do so through Medisave accounts (see below). Beginning in 2021, startups and other newly incorporated businesses that choose to sponsor health insurance for their workers would be required to do so by funding Medisave accounts, thereby giving their workers full ownership over their health care dollars. The Fair Care Act merges the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program (FEHB) into the individual market, creating economies of scale and increasing competition. The bill also repeals the Affordable Care Act’s “firewall” that prevents workers with offers of employer-sponsored coverage from seeking more affordable options in the individual market.

- Medicaid reform. The Fair Care Act gives states the option to replace their expansions of Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act with eligibility for premium assistance in the Fair Care Act’s marketplaces. Because such premium assistance is fully funded by the federal government, whereas Medicaid is partially funded by states, states choosing this option would be required to migrate their legacy Medicaid programs into a per-capita allotment system, closely resembling that of Louisiana Sen. Bill Cassidy’s Medicaid Accountability and Care Act of 2017.

- Medicare Advantage reform. The Fair Care Act introduces competitive bidding into Medicare Advantage, enabling more robust price competition among MA plans that will lower premiums for seniors. The bill also reforms the open enrollment process to include seniors in traditional, fee-for-service Medicare, such that all Medicare enrollees can comparison shop between traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage.

Medisave Accounts, direct primary care, and price transparency

The Fair Care Act substantially strengthens the ability of Americans to save for their out-of-pocket costs, by consolidating and simplifying our current patchwork of tax-advantaged savings accounts — Health Savings Accounts (HSAs), Flexible Spending Accounts (FSAs), Health Reimbursement Arrangements (HRAs), and Medical Savings Accounts (MSAs) — into a single fund called a Medisave Account (MDA).

Based on the Family First Medisave Empowerment Act sponsored by Ohio Rep. Anthony Gonzalez, Fair Care Act Medisave Accounts can be used to purchase the full range of health care goods and services that the older accounts could. The Fair Care Act makes clear that MDAs can be used to purchase direct primary care services, up to $150 per month for an individual and $300 for a family, based on a recent bill introduced by Rep. Dan Crenshaw (Tex.). In addition, MDAs can be used to purchase health insurance for those who wish or need to buy coverage on their own. While MDAs are owned by individuals, not families, MDA holders can transfer money from their MDA to the MDA of a direct relative tax-free, so as to ensure that family members can support each other’s health care needs.

The Fair Care Act increases annual contribution limits for MDAs from $3,600 for individuals and $7,200 for families in 2021 to a range between $3,600 and $5,000 for individuals and $7,200 to $10,000 for families, depending on the actuarial value of one’s insurance; higher-deductible plans will allow for greater tax-free contributions.

In order to accelerate the takeup of MDAs, the Fair Care Act will deposit $1 in an MDA for every $1 contributed by an individual below 400% FPL, and $1 for every $3 contributed by an individual above 400% FPL, up to $1,000 in matching contributions. The bill also authorizes $5 million annually for 5 years to help states and local organizations to educate Americans as to the use of MDAs.

Recipients of advance premium tax credits for the purchase of individual coverage will be able to deposit leftover funds in their MDAs, and states will gain the option to seek a waiver to convert Cost Sharing Reduction subsidies (CSRs) into MDA deposits.

The Fair Care Act also enhances the utility of Medisave accounts by requiring full consumer-facing price transparency for the 100 services that the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services deems most “shoppable” by patients. The bill also furthers price transparency by granting statutory authority to HHS to require disclosure of all prices negotiated between payers and providers, and by establishing an all-payer claims database (APCD) for the same purpose.

Expanding innovation

Innovation in health care is essential to increasing affordability, developing new therapies, and improving the delivery of care. There are many ways in which Congressional statutes and federal regulations have stifled innovation. The Fair Care Act is designed to open up avenues for innovation in all of these areas.

For example, the bill creates a new FDA provisional approval pathway for a broader range of diseases, based on the Promising Pathway Act, sponsored by Sens. Mike Braun (Ind.), Lisa Murkowski (Alaska), and Martha McSally (Ariz.).

Today, the FDA enables drugs for terminal illnesses, such as AIDS or cancer, to receive accelerated approval after mid-stage phase II clinical trials, provided that those drugs show clear indications that they are likely to be successful in larger phase III trials.

The new provisional approval pathway in the Fair Care Act would enable drugs for non-terminal, life-threatening illnesses to also receive provisional approval, on the condition that manufacturers complete phase III trials. The provisional approval would last for two years, and can be renewed for two additional two-year periods. The reform would enable faster and less costly development of new drugs to treat large chronic public health problems like diabetes and cardiovascular disease, which are not terminal, despite their large and serious impact on life expectancy.

In order to ensure that the FDA is accountable for the impact of its regulations on research & development costs, the Fair Care Act requires that any regulation with an economic impact of $100 million or more be confirmed by an up-or-down vote in Congress, based on the Regulations from the Executive in Need of Scrutiny (REINS) Act of 2017, sponsored by Rep. Doug Collins (Ga.) and Sen. Rand Paul (Ky.), among others.

The Fair Care Act also modernizes health care laws related to digital health care, telehealth, and health information technology, for example by making permanent the telehealth reforms introduced during the COVID-19 pandemic. It includes measures that better enable physicians to engage in charity care. For example, it makes permanent telehealth-based reforms introduced during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Medicaid enrollees have poor access to physician care. States have few ways to control Medicaid spending other than by reducing what they pay physicians. As a result, over time, there has emerged a wide disparity between reimbursement rates from Medicaid and private insurance, especially in states with large Medicaid programs. As a result, fewer physicians are willing to see Medicaid enrollees (see below), leading to worse health outcomes for Medicaid enrollees. The Fair Care Act addresses this problem by giving states the option to migrate able-bodied Medicaid enrollees into flexible, subsidized, private insurance marketplaces.

Medicaid reforms

Today, 67 million non-elderly U.S. residents are enrolled in Medicaid and the related Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), including 24 million able-bodied adults, 36 million children, and 7 million blind and disabled individuals. But because of flaws in Medicaid’s design, Medicaid pays doctors far less than Medicare or private insurers do to care for patients. As a result, many Medicaid enrollees have difficulty finding doctors who will see them, leading to poor health outcomes.

The Fair Care Act creates a new option for states to replace their expansions of Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act with a new system, in which all individuals eligible for the Medicaid expansion would instead enroll in private insurance under the Fair Care Act’s individual insurance marketplaces. States would benefit from this arrangement, because under the ACA, they must pay for 10% of the costs of the Medicaid expansion, whereas under the FCA state option, the federal government would pay for all premium and cost sharing assistance. Most importantly, patients would benefit, as they would gain better access to physician care at no extra cost to them, and also enjoy less churn between insurance programs as their incomes go above and below the Federal Poverty Level. We expect that 10 million adults and 10 million children will move from Medicaid and CHIP onto the FCA marketplaces under these reforms.

In exchange for taking this option, states would convert their legacy (pre-ACA) Medicaid programs into per-capita allotments, as originally conceived by President Bill Clinton and refined by Sen. Bill Cassidy (La.). Under the per-capita allotment system, the amount of Medicaid funding would remain the same, but dollars would follow the patient, rewarding states that could deliver better outcomes.

Furthermore, the Fair Care Act would reduce waste, fraud, and abuse in the Medicaid program by allowing states to make more frequent eligibility redeterminations, and by gradually phasing out state provider taxes that drive up Medicaid costs without benefiting enrollees.

Medicaid subsidies and subsidy growth vary widely by type of enrollee. The Congressional Budget Office projects that growth in federal Medicaid subsidies for adults and children will average 5.5% per year, compared to 5.0% for blind & disabled enrollees and 3.3% for elderly Medicaid beneficiaries also enrolled in Medicare. (CAGR = compound annual growth rate.) Under the Fair Care Act’s per-capita allotment reform, states would gain the option to receive federal Medicaid subsidies in a per-capita formula. Under this formula, for example, in 2030 each state would receive $21,510 for each Medicaid enrollee in the blind & disabled category. Per-capita allotment would give states added incentive to deliver high-value care to their Medicaid populations, while keeping Medicaid per-enrollee spending constant relative to current law. (Graphic: A. Roy / FREOPP)

Improving Medicare

The Fair Care Act makes significant improvements to Medicare, increasing the quality of coverage and care available to seniors. As noted above, the bill would require Medigap plans to cover all seniors who enroll, regardless of pre-existing conditions. It would also apply out-of-pocket caps similar to those of Medicare Advantage to the traditional, single-payer, Medicare fee-for-service program.

These reforms will enable a new approach to enrolling seniors in Medicare. Today, seniors in Medicare Advantage enjoy an annual open enrollment period in which insurers compete for their business on the basis of price, benefits, and quality. Traditional Medicare has been insulated from this competition, leading to higher costs and poorer patient outcomes for traditional fee-for-service Medicare (FFS) relative to Medicare Advantage (MA).

Under the Fair Care Act’s competitive enrollment system, based on ideas developed by James Capretta, the open enrollment period would not only include MA plans but also traditional FFS plans under Medicare Parts A and B, along with Medicare accountable care organizations (ACOs). In this way, all seniors will be able to choose among a variety of plans that compete on price and quality in a transparent manner.

Competitive bidding will enable seniors in competitive markets to gain coverage with lower premiums than they pay today, while also reducing the taxpayer cost of subsidizing Medicare Advantage plan sponsors. We expect that 10 million additional seniors will choose MA plans over traditional Medicare under such a system.

The Fair Care Act would enact other reforms that will improve the long-term sustainability of the program, such as site-neutral payment (paying the same rates for the same care, regardless of whether or not it takes place in a hospital or an outpatient clinic), and limiting eligibility for Medicare for the wealthiest 1% of seniors born after 1965.

Truly bending the cost curve

One of the greatest single drivers of rising health care spending is monopoly power. Hospital systems that act as regional monopolies eliminate competition, and force patients and insurers to accept higher prices, especially where patients have no other alternative for care. Barriers to competition in the pharmaceutical industry create and extend artificial monopolies in ways that do not reward innovation.

The Fair Care Act contemplates a number of reforms that would reduce barriers to competition in both the pharmaceutical and hospital sectors. Some of these are derived from bipartisan proposals from Congress and the White House, including the Lower Health Care Costs Act sponsored by Sens. Lamar Alexander (Tenn.) and Patty Murray (Wash.), the leaders of the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions (HELP).

The Fair Care Act establishes grants to states that liberalize their hospital markets by reforming certificate of need laws and other barriers to competition, and it modernizes laws that today restrict competition for off-patent biologic drugs and other complex treatments.

The bill also considers ways of restoring competition to monopoly hospital markets, for example by strengthening antitrust enforcement, and incentivizing regional hospital monopolies to divest their subsidiaries and restore those subsidiaries’ status as independent competitors. Rural Critical Access Hospitals (CAH) would get a 9% boost in Medicare reimbursement rates, in order to ensure their continuing viability and independence during a era of further consolidation. These provisions are based on those in the Hospital Competition Act of 2020, sponsored by Indiana Rep. Jim Banks.

The Fair Care Act also reforms public spending on health care entitlements, by (among other things) means-testing Medicare benefits for the wealthy, establishing an optional per-capita allotment system for Medicaid, and the aforementioned competitive bidding proposal.

Fiscal Impact of the Fair Care Act

The Fair Care Act was designed to increase the number of Americans with health insurance while also reducing federal spending on health care. We estimate that, over a ten-year period ending in 2030, the bill would increase the number of insured U.S. residents by 9 million, while reducing the deficit by $152 billion. The $152 billion in estimated deficit reduction is comprised of $146 billion in reduced spending, and $6 billion in increased revenue.

Provisions with the biggest impact on spending include site-neutral payment in Medicare; the phase-out of state taxes on health care providers; Medicare competitive bidding; federal employee health benefits reform; medical malpractice reform; reinsurance in the Fair Care Act marketplaces; capping out-of-pocket costs for Medicare fee-for-service enrollees; and establishing a market-based alternative to the ACA’s expansion of Medicaid. When combined together, these provisions have a progressive effect; that is, they enable additional financial assistance to lower-income Americans while still reducing overall spending.

Our revenue estimates are static; i.e., they do not take into account the positive impact on economic growth of significantly increased take-home pay from the lower cost of health care under the bill. The most significant provisions affecting revenue include repealing the Affordable Care Act’s 3.8% net investment income tax; the Hospital Competition Act, which, by reducing the cost of hospital care, will increase wages and thereby taxable income; reforming the tax exclusion of employer-sponsored health insurance with a standard deduction of $10,200 for individuals and $27,500 for families; and applying an inflation adjustment to the cost basis of capital gains.

Universal coverage can be achieved with private insurance

As the FREOPP World Index of Healthcare Innovation shows, many countries have achieved universal health insurance with high standards of care using private insurance. Five of the eight highest-ranked countries in our survey—Switzerland (#1), Germany (#2), the Netherlands (#3), Israel (#6), and the Czech Republic (#8)—have universal systems with self-governing private plans and no “public options.”

The Fair Care Act moves the United States in their direction. The bill would expand health care choices for over 100 million Americans, and guarantee that every legal U.S. resident has access to affordable health insurance.

No health care bill is perfect. The Fair Care Act could do even more to reduce the high cost of U.S. health care, to means-test federal assistance, and to auto-enroll individuals in zero-premium coverage, such as for individuals with incomes below the Federal Poverty Level, as suggested by Lanhee Chen and James Capretta. But the Fair Care Act represents an important milestone in health reform: a market-based plan that expands coverage while reducing the deficit.

Some observers believe that coverage cannot be truly called “universal” unless everyone is mandated to purchase coverage. We do not believe that this is a useful measure. What is more important—if not most important—is that health insurance is affordable to anyone who wants it, and that government spending on health care is fiscally sustainable for future generations.

Appendix: Key legislative provisions of the Fair Care Act

Title I. Establishing Medisave Accounts

The Fair Care Act transforms the use of tax-advantaged savings accounts for the purchase of health care services, including insurance, by consolidating Health Savings Accounts (HSAs), Flexible Spending Accounts (FSAs), Health Reimbursement Arrangements (HRAs), and and Medical Savings Accounts (MSAs) into single funds called Medisave Account (MDAs). Under the Fair Care Act, MDAs have the following features:

- The yearly contribution limit ranges from $3,600 to $5,000, depending on the actuarial value of the insurance an individual has obtained, on a sliding scale from 75% to 40%. No individual can deposit more than $50,000 in an MDA tax-free. These contribution limits increase with medical inflation. Individuals with insurance plans with an actuarial value above 80% are not eligible to deposit funds in an MDA unless their plans meet the Medicare Modernization Act’s standard for an HSA-compatible High Deductible Health Plan. MDAs can be spent on health care services only after an individual has purchased health insurance legally issued in his or her state of residence.

- Unused advance premium tax credits (APTCs) can be deposited into MDAs. For example if an individual with income near the poverty line purchases the lowest-cost Silver plan in a given market instead of the second-lowest-cost benchmark Silver plan, he or she can keep the difference in price between the two plans.

- MDAs are owned by individuals, but their value can be transferred to immediate relatives without a tax penalty.

- The consolidation of legacy savings accounts into MDAs will occur over a one-year transition period. The federal government will help seed MDAs on a one-time basis by offering $1 for every $1 in contributions to the MDA for individuals with incomes below 400% of the Federal Poverty Level, and $1 for every $3 in contributions for those above 400% FPL.

- MDAs can be used to purchase direct primary care.

- In a manner similar to the way employers can now fund their workers’ Health Reimbursement Arrangements so that their workers can purchase nongroup insurance, the Fair Care Act enables employers to deposit funds in Medisave accounts to purchase health insurance. Companies formed after January 1, 2022 that wish to sponsor health coverage for their workers will be required to do so in this manner.

- The FCA integrates the Federal Employees Health Benefits (FEHB) program into the Fair Care Act’s insurance marketplaces. Going forward, federal employees will receive a Medisave deposit equal to the price of the benchmark Silver plan in their area, instead of purchasing insurance in a separate market. This integration will create economies of scale for the nongroup marketplaces, reducing prices for all.

Title II. Improving private health insurance

In the event that the Supreme Court rules unconstitutional the ACA’s approach to guaranteeing coverage for those with preexisting conditions, the Fair Care Act reinstates those provisions by adding them to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA), a mechanism first proposed by Virginia Rep. Denver Riggleman in the Protecting Patients with Preexisting Conditions Act. The Fair Care Act reinstates coverage mandates for adult children under 26 using the same mechanism.

The Fair Care Act seeks to reduce premiums in the individual market by, among other things:

- Making insurance more affordable for younger and older individuals, by widening the ACA’s “age bands” to 5:1, age-adjusting the ACA’s advance premium tax credits to improve affordability for the young, and extending eligibility for premium assistance up to 600% of the Federal Poverty Level;

- Enabling consumers to choose affordable “Copper plans” with a 50 percent actuarial value;

- Enabling states to hold open enrollment period biennially or triennially, instead of annually, as a way of aligning insurance plans with patients’ longer-term health outcomes;

- Offering states additional flexibility to improve their individual markets;

- Establishing a guaranteed coverage pool reinsurance program that directly subsidizes coverage for those with pre-existing conditions, thereby lowering premiums for healthy individual market enrollees;

- Significantly expanding the size of the individual market (see below), creating economies of scale, a more attractive risk pool, and thereby greater insurer participation and competition;

- For those who need further affordable options, the Fair Care Act enables the establishment of Association Health Plans, short-term limited duration plans, and “Copper plans” with a 50 percent actuarial value.

The Fair Care Act would also enable more workers with employer-based coverage to find better deals in the individual market, by removing the ACA’s “firewall” that prevents workers from doing so; repealing the ACA’s employer mandate; enabling the establishment of Association Health Plans; and improving the ability of consumers to purchase health insurance across state lines.

Title III. Competition, transparency, and accountability

Subtitle A: Provider and insurer competition

The Fair Care Act would end the vicious cycle of hospital consolidation, price hikes, and insurer consolidation, using several tools:

- Quintupling funding for the Federal Trade Commission (an additional $160 million) for the exclusive purpose of increasing the size of its antitrust staff investigating hospital consolidation;

- Prohibiting hospitals from imposing anti-competitive contract provisions, such as anti-steering clauses and gag clauses, upon payers;

- Providing the FTC with jurisdiction to enforce antitrust laws with regards to anticompetitive practices by non-profit hospitals;

- Authorizing the HHS Secretary to award up to $1 billion in grants to states that take specific steps to improve hospital competition, such as eliminating Certificate of Need or Any Willing Provider laws;

- Repealing incentives to form hospital-led Accountable Care Organizations that lead to highly consolidated provider markets;

- Repealing the ACA ban on the construction of new physician-owned hospitals;

- Enabling private insurers in a given state to jointly negotiate reimbursement rates and network access with regional hospital systems;

- Enacting site-neutral payment from Medicare for health care services performed in a hospital-owned facility and a non-hospital-owned facility;

- Incentivizing regional hospital monopolies to divest their subsidiaries and restore a competitive market, by requiring hospitals in extremely concentrated markets to accept Medicare Advantage rates from all payers (with exemptions for rural areas), with hospitals and payers free to negotiate rates that are lower than MA rates in these settings;

- Barring gag clauses on price and quality information, and banning anti-competitive terms in payer-provider contracts; and

- Eliminating the McCarran-Ferguson antitrust exemption for health insurance plans.

In order to ensure that as many rural hospitals as possible remain independent, the Fair Care Act increases funding for Critical Access Hospitals, by increasing Medicare’s reimbursement rates to 110 percent of allowable costs, up from 101 percent.

Subtitle B: Price transparency

The Fair Care Act also seeks to give patients more transparency into their health care spending, and more tools to manage their out-of-pocket expenses, by:

- Requiring hospitals to publish, in a standardized digital format, average prices for their 100 most common shoppable services;

- Granting HHS the statutory authority to require that providers and payers disclose their negotiated prices;

- Establishing a national all-payer claims database to create transparency into prices negotiated by insurers and providers, including those covered under ERISA plans exempt from state regulation;

- Requiring insurers to have up-to-date directories of their in-network providers;

- Ensuring enrollee access to cost-sharing information;

- Ensuring patient ownership of personal medical data;

- Requiring that health care facilities give patients bills for performed services within 45 days;

- Establishing an advisory group to consult with the HHS Secretary on administrative burdens faced by hospitals that increases costs;

- Requiring transparency in the 340b drug discount program;

- Expanding the role of employers in communicating to workers how much is being taken out of their paychecks to cover health care costs;

- Requiring that insurers submit to the HHS Secretary an annual report on health claims spending; and

- Requiring a Government Accountability Office report on profit-sharing relationships between the hospitals, contract management groups, and physician and ancillary services.

Subtitle C: Prescription drug competition and innovation

The Fair Care Act would expand price competition for prescription drugs by, among other things:

- Addressing attempts by branded companies to restrict supply of their drugs so as to prevent generic manufacturers from acquiring the samples they need to develop generic alternatives;

- Creating an abbreviated approval process for “complex generics,” such as off-patent drugs that are delivered via a specialized delivery device like an injector, a patch, or an inhaler;

- Aligning the biosimilar market with the generic drug market, such that off-patent biologic drugs can be substituted for brand-name biologics at the pharmacy level, just as generics are, including for secondary indications; and assigning a minimum of 5 years of market exclusivity to new clinical entities whether biologic or small molecule, regardless of patent status (today biologics enjoy 12 years of exclusivity regardless of intellectual property, compared to 5 years for small molecules);

- Requiring biologic drug manufacturers to disclose their relevant patents ahead of time in a transparent manner;

- Creating a new FDA accelerated approval pathway to help safe and effective drugs for life-threatening diseases reach the market after phase II clinical trials;

- Maximizing the number of times a single orphan drug can receive separate market exclusivities;

- Enabling HHS to regulate the manipulation of copay assistance by drug companies seeking higher prices;

- Ending the role of pharmacy benefit manager rebates in driving over-utilization of high-priced drugs where low-cost alternatives are available to commercially insured patients;

- Enabling private insurers in a given state to jointly negotiate with drug manufacturers for prices and formulary access; and

- Requiring an up-or-down vote from Congress on any new FDA regulation that has an economic cost exceeding $100 million.

Subtitle D: Prescription drug and PBM transparency

The Fair Care Act reforms policies that limit the ability of generic biologic drugs, or “biosimilars,” to enter the market, by:

- Requiring that branded biologic manufacturers publicly disclose the patents they intend to enforce at the launch of their drugs, so that biosimilar manfacturers can plan accordingly;

- Requiring that all relevant patent information for biological products be published in the FDA’s “Purple Book,” along with licensure status and exclusivity periods;

- Modernizing the FDA’s “Orange Book” for small molecule drug patents such that invalid or inoperative patents are removed from the publication; and

- Modernizing the FDA’s regulation of labeling and package inserts for generic drugs.

The bill also reforms the role of pharmacy benefit managers, or PBMs, in managing prescription drug benefits, by:

- Eliminating the role of pharmacy benefit manager rebates in steering patients to cost-ineffective drugs;

- Requiring PBMs to disclose to insurers the costs, fees, and rebate information associated with their contracts;

- Eliminating the ability of PBMs to retroactively charge pharmacies for price increases; and

- Commissioning the U.S. Comptroller General to conduct a study on the relationship of PBMs to lower or higher drug costs.

Subtitle E: Medicare & Medicaid prescription drug reforms

Today, the Medicare program rewards drug manufacturers for raising prices, by increasing the incentives for physicians to prescribe high-priced drugs even when a more effective, low-cost option is available. The Fair Care Act addresses this problem by:

- Creating statutory authority for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to establish reimbursement rates for Medicare Part B drugs based on international reference prices;

- Capping subsidy growth to pharmaceutical companies for Part B drugs to consumer inflation;

- Directing the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation to conduct a pilot program to determine the efficiency and effectiveness of an integrated drug benefit for individuals enrolled in Medicare parts A, B, and D; and

- Repealing the artificial cap on discounts in the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program.

Subtitle F: Medical malpractice reform

The Fair Care Act reforms medical malpractice law, by:

- Requiring malpractice lawsuits to occur no longer than 3 years after the relevant medical treatment or no longer than 1 year after a patient discovers that he or she is injured;

- Limiting non-economic damages from malpractice litigation to $250,000;

- Capping attorney contingency fees to 40% of the first $50,000 recovered, 33% of the next $50,000, 25% of the next $500,000, and 15% of any amount above $600,000, so that the majority of damages are awarded to patients, not lawyers;

- Requiring periodic payments of damages so as to minimize the risk of bankrupting physician practices;

- Immunizing health care providers from product liability for lawful use of FDA-approved prescription drugs and medical devices;

- Limiting physician expert witnesses to those licensed to practice in the defendant’s state or a contiguous bordering state, and practicing in a specialty that is relevant to the case;

- Specifying that physician apologies or other expressions of sympathy are inadmissible for any purpose as evidence of an admission of liability in a malpractice lawsuit; and

- Limiting the liability of physicians who volunteer their time and resources to provide medical services or charity care.

Title IV. Medicare & Medicaid reforms

The Fair Care Act makes significant improvements to both Medicare and Medicaid, increasing the quality of coverage and care available to seniors and to low-income Americans, and focusing public assistance more on those who need it: the poor, the sick, and the vulnerable.

Subtitle A: Medicaid reforms

The Fair Care Act makes significant improvements to Medicaid, increasing the quality of coverage and care available to individuals with incomes near or below the Federal Poverty Level, by:

- Creating a state option to replace ACA Medicaid expansions with eligibility for Fair Care Act marketplace-based coverage, alongside per-capita allotments for legacy Medicaid enrollees;

- Enabling states to regularly redetermine enrollee eligibility for Medicaid, in order to limit waste, fraud, and abuse;

- Gradually phasing out the safe harbor for Medicaid state provider taxes, from 6% in 2020 to 4% from 2021–29, 3% from 2030–35, 2% from 2035–40, 1% from 2040–45; and 0% from 2045 onward; and

- Establishing a tax deduction for charity primary care.

Subtitles B & C: Medicare reforms

The Fair Care Act establishes important consumer protections for seniors enrolled in the traditional, single-payer, fee-for-service Medicare program, reduces waste, fraud, and abuse, and expands choices for all seniors enrolled in Medicare, by:

- Establishing a competitive enrollment and bidding system for Medicare plans, including traditional fee-for-service, Medicare Advantage, and Medicare accountable care organizations;

- Capping out-of-pocket costs in traditional Medicare, and requiring guaranteed issue regardless of pre-existing conditions in Medigap plans;

- Reforming Medicare accountable care organizations so that they are fully risk-bearing, further incentivizing cost-effective care;

- Establishing a unified enrollment and competitive bidding system for fee-for-service Medicare, Medicare Advantage, and Medicare Accountable Care Organizations, such that all seniors in both systems would participate in an annual open enrollment process in which they can compare prices, benefits, and quality for both traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage plans;

- Enacting an out-of-pocket cap for fee-for-service Medicare, aligned with the out-of-pocket caps already established in Medicare Advantage;

- Barring late enrollment penalties for Medicare applicants who had creditable coverage prior to enrollment;

- Requiring that supplemental Medigap plans offer coverage to anyone who applies, regardless of pre-existing conditions;

- Requiring Medicare Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) to accept two-sided risk-bearing contracts;

- Enabling the use of direct primary care in Medicare;

- Establishing site-neutral payment for all services paid for by both Medicare Parts A and B, so that health care services provided in outpatient clinics are paid at the same rate as identical services delivered by hospitals;

- Migrating federal employees from the FEHB annuitant program into Medicare Advantage;

- Ceasing eligibility for Medicare Parts B and D for multimillionaires in the top 1%; specifically, those whose lifetime earnings exceed $10 million and were born on or after 1965;

- Restoring the tax deduction for employers who sponsor Medicare Part D coverage for their retirees; and

- Reducing Medicare subsidies for hospitals’ bad debt from 65% of debt to 25% over a four year period, meaning that hospitals will be expected to cover a greater share of their own billing shortfalls.

Subtitle D: Telehealth improvements & expansion

The Fair Care Act incorporates a version of the CONNECT for Health Act, sponsored by Sens. Brian Schatz (Hawaii), Roger Wicker (Miss.), Ben Cardin (Md.), John Thune (S.D.), Mark Warner (Va.), and Cindy Hyde-Smith (Miss.), and Reps. Mike Thompson (Calif.), Peter Welch (Vt.), David Schweikert (Ariz.), and Bill Johnson (Ohio), enabling Medicare to reimburse for telehealth services such as diabetes care, physical therapy, mental health services, emergency medical care, and hospice care. The bill removes geographic restrictions on the ability of Federally Qualified Health Centers and rural health clinics to offer telehealth services.

The Fair Care Act also enables the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation to test telehealth models in Medicare, and requires CMS to conduct an analysis of the impact of telehealth waivers and innovation models.

Tax provisions

Along with the measures described above, the Fair Care Act includes three additional tax provisions, related to changes made by the Affordable Care Act in 2010. First, the Fair Care Act reforms the tax exclusion of employer-sponsored health insurance by including a standard deduction of $10,200 for individuals and $27,500 for families. In order to preserve the revenue neutrality of the Fair Care Act, this provision is offset by applying an inflation adjustment to the cost basis of capital gains for tax purposes, and by repealing the Affordable Care Act’s 3.8% tax on net investment income.

">

">