Inflation is far worse than you think

New Email Platform: We’ve moved FREOPP’s newsletter over to Substack, which, as you may know, has become the best platform for substantive email newsletters. If you’ve received this email from a colleague or friend, please click here to receive our updates directly. If you’d like to unsubscribe, scroll to the bottom of this email, or just hit “reply” and drop me a line. And if you think Substack is great, let us know that too!

The Big Idea: FREOPP’s work has long focused on how poorly designed government policies make everyday life more expensive, especially for those who live paycheck-to-paycheck. Official government statistics, like the Consumer Price Index, vastly understate the scale of the problem. Can bitcoin help them fight back?

What We’re Doing: What aren’t we doing? So much to catch you up on. FREOPP’s work on reopening schools during the pandemic helped 53 million kids regain in-person learning. We broke down the expected financial value of every major at every college, grad school, and community college in America. We documented how rising drug prices do little to drive pharmaceutical innovation.

New Additions: We landed new scholars in nuclear energy, macroeconomics, housing, immigration, and social mobility. In February, Melanie Hildreth joined us to serve as our Chief of Staff.

What I’m Reading: Jeffrey Garten’s long-overdue account of Nixon’s departure from the Bretton Woods accords, Three Days at Camp David: How a Secret Meeting in 1971 Transformed the Global Economy, provides the context for arguably the most consequential economic decision of our lives.

The Big Idea: Inflation is driving economic inequality

As of the end of March, the U.S. government’s most widely-used measure of inflation—the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers, usually abbreviated as CPI-U—rose at an annual rate of 8.5%. That’s the highest rate since December 1981. That’s bad enough news as it is. But it gets worse, when you consider how inflation affects people in different economic circumstances.

If you’re wealthy, you’re far more likely to be a beneficiary of inflation than a victim of it. Home prices appreciated 20% in the last year, which means that if you owned an expensive home, your net worth went up far more than your daily expenditures did.

In addition, as we will show in a forthcoming paper from FREOPP scholars Jackson Mejia and Jon Hartley, one problem with official measures of inflation is that they’re geared toward describing the consumption patterns of the average American. So what happens if you’re not average?

The CPI-U measures a so-called “market basket”: a weighted index of the prices of various goods and services that the U.S Bureau of Labor Statistics thinks that the average American buys. But lower-income Americans spend a greater share of their earnings on everyday necessities, relative to higher-income Americans. That means lower- and middle-income Americans are harmed more by inflation than the wealthy.

Despite all the talk from the U.S. Federal Reserve last year that inflation was going to be “transitory,” these price increases permanently destroy the purchasing power of the U.S. dollar. And inflation is likely to stay high for a while, not just because of COVID and Ukraine. About one-third of the CPI-U’s market basket is based on surveys related to home prices. But while home prices appreciated 20% in the last year, the government’s official measure of housing inflation is only up 5%. In other words, if the government used a more accurate measure of housing inflation, CPI-U would be 13.5%, not 8.5%.

Absent public policy changes, how can Americans protect themselves from inflation? Last October, I argued in a piece for National Affairs that bitcoin has emerged as an attractive way for ordinary people to protect their savings from inflation over the mid- to long-term. The article, and an accompanying paper for FREOPP, make the case that the rising federal debt is an underappreciated driver of inflation: one that is only going to get worse with time.

What We’re Doing: Fighting the rising cost of living

When we founded FREOPP in 2016, my dream was that we could tackle the biggest issues affecting Americans on the bottom half of the economic ladder. We require that all our scholars’ policy ideas meaningfully improve the lives of Americans whose incomes or wealth are below the U.S. median, using the tools of individual liberty, free enterprise, technological innovation and pluralism.

Practically, that means that a lot of our work revolves around the rising cost of living. For example: Preston Cooper, our higher ed scholar, has put together an incredible series of analyses of the return on investment for colleges, grad schools, and community colleges, by major or field of study. (The whole series is available at roi.freopp.org.) If you’re a parent who is trying to figure out if your kid’s major is going to pay off down the road, Preston has taken new data on average incomes after graduation by major and school, and cross-referenced that data to schools’ costs and data on long-term income growth by occupation. Preston’s work will fundamentally transform the way we hold colleges and universities accountable for their tuition hikes. I can’t do it justice in an email—you’ll have to check it out for yourself.

Health care: Surveys indicate that prescription drug prices are one of Americans’ top concerns. Gregg Girvan and I put out a paper contravening the oft-repeated claim that high drug prices are necessary to fund innovation. It turns out that outsized profits from high-priced pharmaceutical incumbents rarely yield new medicines. The best new drugs, in fact, come from unprofitable startups. To aid them, we need to lower the cost of bringing drugs to market, through reforms of the FDA.

Housing: Roger Valdez has a series of articles up at Forbes describing how housing development and zoning regulations increase the price of housing.

COVID-19: Policies related to the pandemic affected the cost of everyday life in manifold ways. One of those ways, highlighted by Dan Lips, was school closures. School closures forced many parents to spend more on child care, and forced millions of parents—especially moms—out of the workforce. School closures were a tragic mistake, and inexcusable during the omicron wave when vaccines for parents were widely available.

New Additions

Over 16 years at the Institute for Justice, Melanie Hildreth raised more than $125 million and helped make IJ the country’s leading public interest law firm for classical liberal principles. In February, Melanie joined FREOPP, as our Chief of Staff, to help take us to the next level. You’ll be hearing from Melanie soon!

We’ve recently added a trove of new scholars:

- Grant Dever: Grant’s work focuses on how to drive the U.S. toward abundant, reliable, affordable, low-carbon energy like nuclear power and natural gas.

- Jackson Mejia: Jackson is a Ph.D. candidate in the MIT economics department, who is doing terrific work for us on inflation.

- Judge Glock: Judge is a brilliant mind and a leading thinker on homelessness, who also serves as the Chief Policy Officer at the Cicero Institute, an Austin-based think tank.

- Natalia Dashan: Natalia, who emigrated to the U.S. from Russia, and went on to graduate from Yale, will help us think about how to reform America’s system for legal immigration.

- Aparna Mathur: Aparna spent 16 years at the American Enterprise Institute before serving for a year at the Council of Economic Advisers. Today, along with being a Visiting Fellow at FREOPP, she serves as an economist at Amazon and as a fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School, where she is researching how much the trillions we spent on COVID-19 relief helped ordinary people.

Finally, we added three stellar people to our Board of Advisors: Garrett Johnson, co-founder of the Lincoln Network and former Rhodes Scholar; Marty Makary, the Johns Hopkins surgeon who is America’s leading advocate for price transparency; and Byron Sanders, President & CEO of Big Thought, an education reform non-profit. Welcome all!

What I’m Reading: Jeffrey Gartens’ Three Days at Camp David

The National Affairs article I mentioned above, entitled “Bitcoin and the U.S. Fiscal Reckoning,” begins with a discussion of one of the seminal moments in U.S. economic history: President Nixon’s 1971 departure from the World War II-era Bretton Woods agreement that pegged the value of a dollar to price of 1/35th of an ounce of gold, and pegged the rest of the Allies’ currencies in turn to the U.S. dollar.

As I write in the piece, the decision led to raging inflation in the 1970s:

By December 1980, the dollar had lost more than half the purchasing power it had back in June 1971 on a consumer-price basis. In relation to gold, the price of the dollar collapsed—from 1/35th to 1/627th of a troy ounce. Though Jimmy Carter is often blamed for the Great Inflation of the late 1970s, “the truth,” as former National Economic Council director Larry Kudlow has argued, “is that the president who unleashed double-digit inflation was Richard Nixon.”

You’d think that this episode would have already been the subject of several book-length treatments. But as far as I know, we had to wait 50 years before such a book, from former Yale School of Management dean Jeffrey Garten. It’s called Three Days at Camp David: How a Secret Meeting in 1971 Transformed the Global Economy.

The book highlights how haphazard the decision was to leave the gold standard once and for all. The principal driver of the decision was Nixon’s Treasury Secretary, John Connally, a nationalist from Texas who felt that Bretton Woods helped Europe and Japan more than America. But it was also supported by Milton Friedman, who argued that free-floating exchange rates were the market way to go.

The book also makes clear that Nixon, in the end, had no choice. Rising trade and budget deficits made it impossible for the U.S. to maintain its gold reserves without dramatically devaluing the dollar.

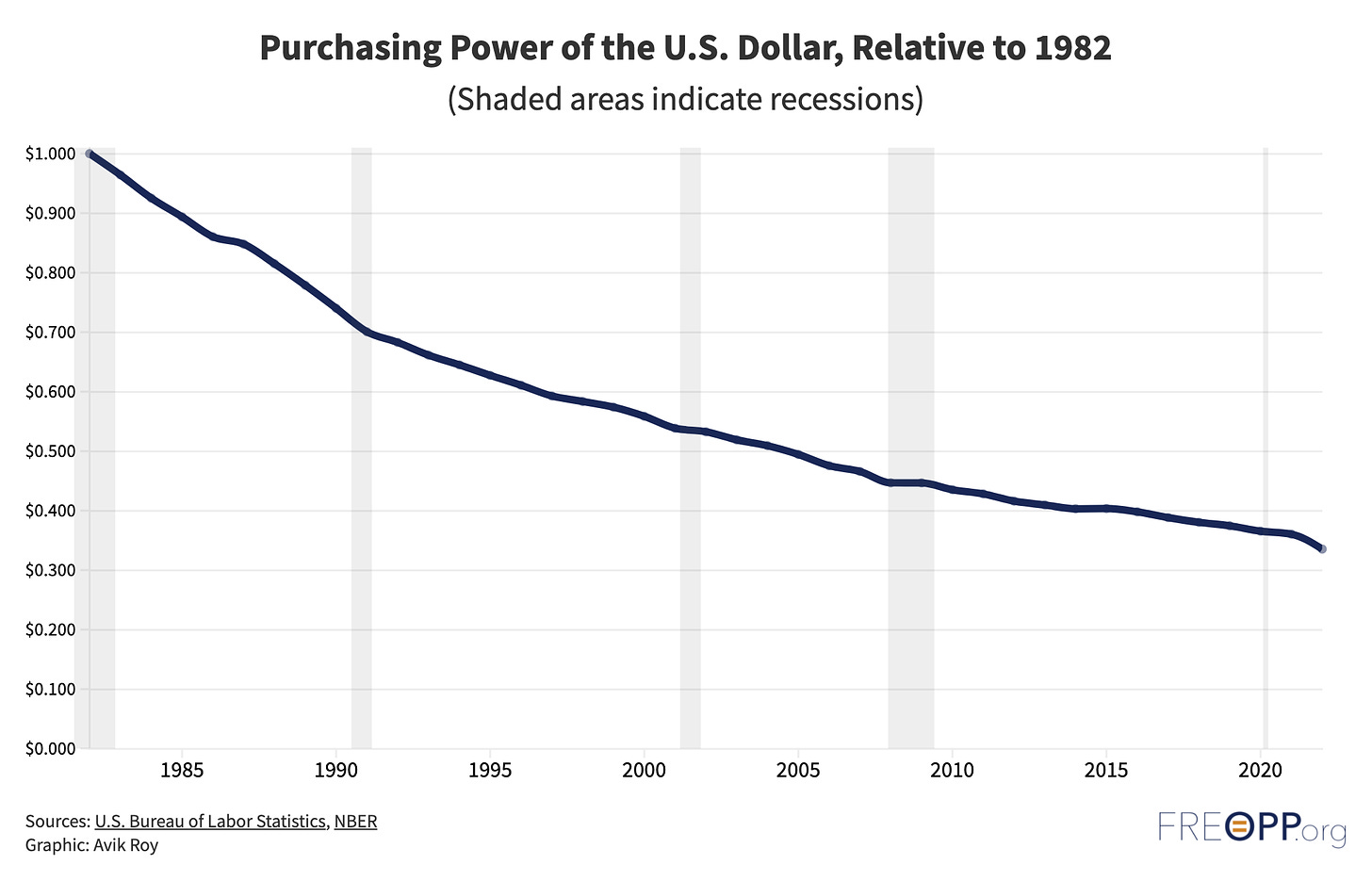

The crazy thing is, we think of the period from 1982 to 2021 as the golden age of well-managed monetary policy, with low and steady inflation. But as the above chart shows, since 1982, the U.S. dollar has lost more than two-thirds of its purchasing power. Even 2% inflation, over a long enough period, is a pernicious destroyer of Americans’ hard-earned savings.

More on that—and how to fix it—in my next letter.

Sincerely,

Avik Roy, President

The Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity

Subscribed

">

">