Executive Summary

On November 1, 2019, presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren (D., Mass.) published a lengthy monograph describing how she would pay for her plan to replace the U.S. health care system with a single, federally-run insurance agency: what she describes as “Medicare for All.”

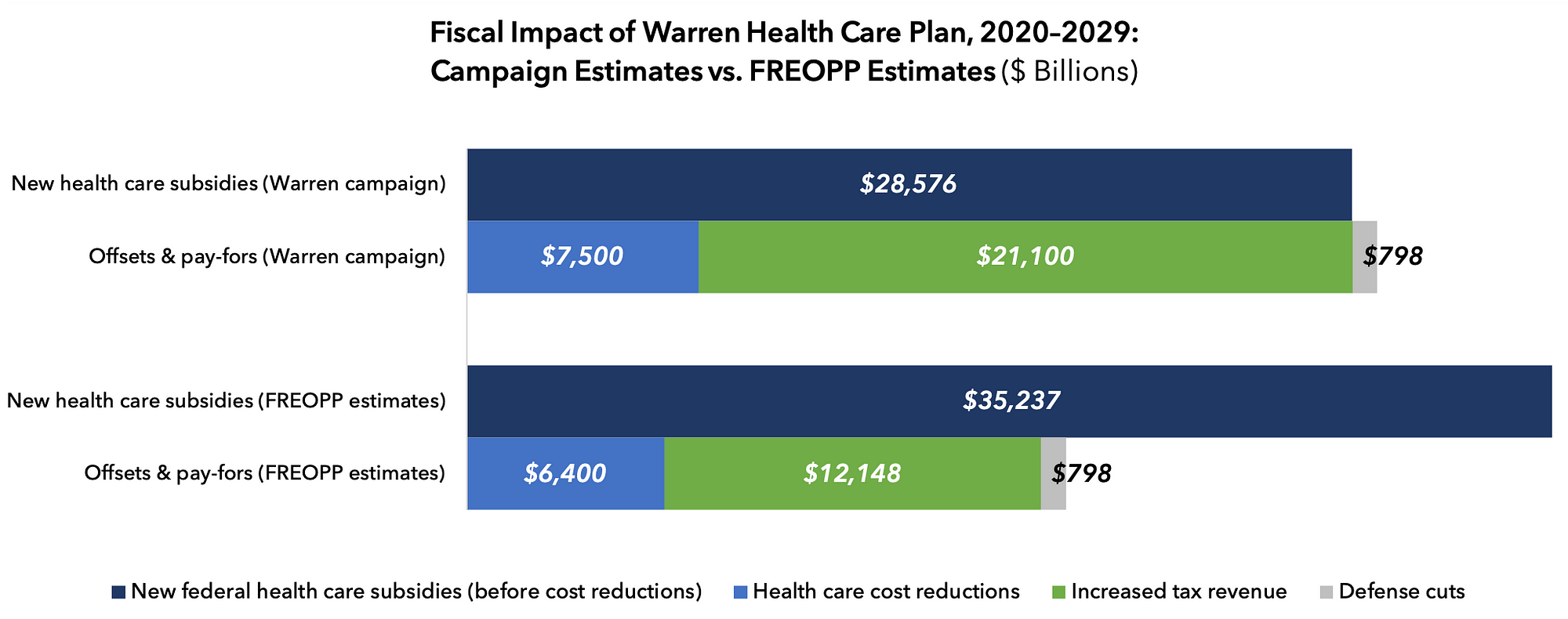

In this paper, we analyze each of Warren’s proposals in detail. While some of Warren’s proposals would in fact succeed in raising taxes or reducing spending, others would not. All in all, while Warren and her advisors estimate that her proposals would fully fund “Medicare for All,” we estimate that, altogether, the Warren plan would increase the primary federal deficit by $15 trillion over ten years. (We did not calculate the cost of interest payments to service $15 trillion of additional borrowing.)

For the purpose of our calculations, we assumed that each one of Warren’s policy proposals becomes law, even though many would be difficult to enact. In other words, the difference in our estimates comes entirely from a difference in our assessment of the policy effects of the changes Warren proposes.

While Warren’s stated goal of universally affordable health insurance is a salutary one, her plan is likely to make U.S. health care far less affordable in the medium to long run. There are other ways to achieve universal coverage that increase the affordability of the system for future generations.

Warren’s tax increases will raise less revenue than she expects. Warren and her advisors estimate that her proposed tax increases and other policy changes will increase federal revenue by $21.1 trillion from 2020 to 2029; we estimate that they will raise $12.1 trillion over that period. We estimate that slower economic growth will lead to a loss of $3.3 trillion in additional tax revenue, and that the size of the U.S. economy will be 12.5% smaller in 2029 due to a decade of slower economic growth. Slower job growth will primarily harm those whose incomes and employment prospects are below the U.S. median.

Elimination of patient cost-sharing will lead to soaring demand for health care services. Warren and her advisors are also overly optimistic about the cost savings that can come from “Medicare for All” in the absence of rationing access to expensive health care services. Warren proposes eliminating all deductibles, co-pays, and premiums; this will lead to substantially higher demand for health care services. We conservatively estimate a 10% increase in demand above the Warren estimates, costing $3.4 trillion over the next decade. Furthermore, the Warren plan does nothing to increase the supply of health care providers to keep pace with this soaring demand. Again, those whose incomes or wealth are below the U.S. median will have the most difficulty accessing care in such an environment.

Increased waste, fraud, and abuse. It is widely estimated that at least 10% of Medicare spending is waste, fraud, and abuse, due to Medicare’s policy of rarely questioning claims from health care providers. Applying a 9% fraud ratio to the new Medicare spending under Warren’s plan leads to $3.1 trillion in additional waste, fraud, and abuse. This waste is far more likely under Warren’s plan, which deliberately underfunds the administrative infrastructure necessary to root out wasteful spending.

Warren’s plan will disrupt capital markets, blue-collar employment, immigration policy, and national security. Non-fiscal aspects of Warren’s plan could have extremely disruptive consequences to the U.S. economy, but were beyond the scope of this paper. For example, her plan to tax unrealized capital gains and financial transactions could lead to substantial outflows and volatility in U.S. securities markets. Her proposal to increase taxes on businesses’ capital expenditures would have a substantially negative effect on the U.S. manufacturing sector and on employment of blue-collar workers. Her plan to increase the U.S. corporate tax rate to 35% will drive companies and jobs out of the U.S. and into more favorable tax jurisdictions. Her policy of providing unlimited health care subsidies to undocumented immigrants will increase the volume of illegal immigration to the U.S. And her proposal to end $798 billion in Congressional appropriations for overseas contingency operations could be disruptive to U.S. foreign policy and national security.

How the Warren plan expands coverage

Sen. Warren’s proposal would establish universal coverage with a single government payer for all U.S. residents, including illegal immigrants. While she often describes her plan as “Medicare for All,” it would end Medicare as we know it, and replace it with a meaningfully different health care system.

Abolition of private insurance. Today, more than one-third of Medicare enrollees are enrolled in private major medical insurance through Medicare Advantage, also known as Medicare Part C. Under Medicare Advantage, seniors choose among a wide variety of private insurance plans to deliver Medicare’s coverage of hospital and outpatient physician services. In addition, nearly all seniors are enrolled in private prescription drug coverage through Medicare Part D. Under the Warren plan, these coverage options would be abolished and replaced with a single, government-run insurance agency. The Warren plan also abolishes private insurance for those who currently purchase it on their own or receive it from their employers.

Abolition of direct patient spending. Unlike Medicare, the Warren plan would not charge premiums, co-pays, deductibles, or co-insurance. All health care goods and services would be free to the patient at the point of care, mostly financed by a substantial increase in taxes (we discuss this more extensively below).

Expansion of coverage to all U.S. residents, including undocumented immigrants. Every U.S. resident would be eligible for fully subsidized health insurance, regardless of immigration status. This element of the Warren plan stands in contrast to the Affordable Care Act, which restricted eligibility for health insurance subsidies to legal residents of the U.S.

Substantial fiscal effects. A group of economists at the Urban Institute and the Commonwealth Fund, led by Linda Blumberg, recently sought to estimate the fiscal effects of various Democratic proposals to expand health insurance coverage. What the Urban group describes as “Reform 8: Single-payer with enhanced benefits and no cost-sharing requirements” closely simulates the Warren plan’s coverage expansion. Urban estimates that Reform 8 would increase federal spending by $33,988 billion from 2020 to 2029, partially offset by $1,972 in tax revenue due to the abolition of employer-sponsored insurance (because workers and employers would not be paying for private insurers, and because the value of employer-sponsored insurance is excluded from taxation, workers would, in theory, have more taxable income). The Urban economists estimate that total national health care spending would increase by $6 trillion, due to “higher costs associated with additional covered benefits, no cost-sharing requirements, and larger insured population (including about 11 million undocumented immigrants).”

The Warren plan’s efforts to reduce health care spending

Sen. Warren relied on two policy advisers, Donald Berwick of Harvard Medical School and Simon Johnson of the MIT Sloan School of Management, to identify ways to reduce the $34 trillion cost of establishing a single, federal health insurance program for all U.S. residents. In a letter to Sen. Warren, they identify five ways to reduce federal health spending, relative to the Urban Institute’s estimates:

- Maintain state & local health care spending ($6.1 trillion). From 2020 to 2029, state and local governments will spend approximately $3.2 trillion on Medicaid, and $3.0 trillion on employer-sponsored insurance and payroll taxes for government employees. Berwick and Johnson believe that these funds can be repurposed in order to fund the new federal single-payer system.

- Reduce administrative costs to 2.3% ($1.8 trillion). The Urban Institute economists estimate that a single-payer health care system will require administrative costs of 6 percent of total health spending. “Because a single-payer approach exposes the federal budget to greater financial risks than other reforms, processes to prevent fraud and abuse and programs to manage care and monitor quality and access under centralized provider payment rates will be even more important than they are today,” they write. “We believe 3 percent administrative costs would be insufficient to carry out necessary tasks.” Berwick and Johnson disagree; they estimate that by reducing administrative costs from 6% to 2.3%, they can save $1.8 trillion.

- Prescription drug reform ($1.7 trillion). The Warren plan adapts, and goes beyond, three Democratic bills aimed at lowering prescription drug prices: H.R. 3, the Lower Prescription Drug Costs Now Act; H.R. 1046, the Medicare Negotiation and Competitive Licensing Act of 2019; and S. 3375, the Affordable Drug Manufacturing Act. In combination, these bills would empower the federal government to directly negotiate prescription drug prices for all U.S. residents, with the aim of “overall average prices for branded drugs slightly below current Medicaid prices.” The Warren plan would also enable the federal government to “override [a drug’s] patent” and license the patent to another manufacturer, if the original manufacturer refused to accept the federally negotiated price.

- Medicare provider payment reform ($2.9 trillion). The Warren plan includes a number of reforms of the way hospitals and doctors are paid. Doctors would be reimbursed at Medicare rates, as modeled by Urban. Hospitals would be paid 110% of Medicare rates compared to 115% of Medicare in the Urban proposal, leading to $600 billion in savings. Warren mirrors a Trump administration proposal to enact site-neutral payment for physician services, saving $500 billion. Reforms for payment of post-acute care would save another $500 billion, and instituting bundled payments for inpatient care and 90 days of post-acute care would save $1.2 billion. Expanding Medicare’s use of value-based payment models would save another $100 billion.

- Slowing medical cost growth over time ($1.1 trillion). On top of these other reforms, the Warren advisors assume that additional reforms such as “global budgets, population-based budgets, and automatic rate reductions” would slow the annual growth of health care spending from 4.5% under the Urban model to 3.2%, because Taiwan, which recently instituted a single-payer health care system, has slowed health care growth to 3.2%.

The Warren plan’s tax increases

Sen. Warren relied on three advisors—Simon Johnson of MIT, Betsey Stevenson of the University of Michigan, and Mark Zandi of Moody’s Analytics to develop a plan to pay for increased health care spending through tax increases. In a separate letter to Sen. Warren, Johnson, Stevenson, and Zandi identify seven opportunities for increased tax revenue:

- Payroll tax on employers of full-time workers ($8.8 trillion). Because employers would no longer be able to sponsor private health insurance for their workers, the Warren plan assesses an $8.8 trillion payroll tax on employers to pay for that change. While the swap of employer-sponsored insurance for a payroll tax is designed to reduce total costs of sponsoring health insurance by 2% on average, there would be winners and losers. Specifically, employers who pared down the value of their health coverage would be assessed a lower tax than those with more generous coverage. Businesses with fewer than 50 employees that do not sponsor coverage today would be exempt from the tax, incentivizing those who do to drop coverage. In addition, employers with a unionized workforce would enjoy a lower payroll tax rate. Independent contractors below an unspecified income threshold would be exempt from the payroll tax.

- Increase in taxable income ($1.15 trillion) and abolition of Health Savings Accounts ($250 billion). The Warren advisors estimate that Americans will spend $3.7 trillion from 2020–2029 on their share of premiums for employer sponsored insurance; if workers are able to retain this income, it will become taxable income, generating $1.15 trillion in additional revenue. The plan abolishes tax deductions for health savings accounts (HSAs) and for individual medical expenses in excess of 10% of adjusted gross income, raising $250 billion.

- Taxes on financial transactions ($800 billion) and large financial institutions ($100 billion). The Warren plan imposes a 0.1% tax on all purchases of stocks, bonds, and derivatives. For stocks and bonds, the tax would be assessed on the value of the security; for derivatives, as a percenrage of “all payments actually made under the terms of the derivative contract.” In 2018, the Joint Committee on Taxation estimated that this tax would raise $777 billion from 2019–2028; the Warren advisors estimate that moving the window to 2020–2029 increases the revenue received to $800 billion. In addition, the Warren plan assesses a fee on financial institutions with more than $50 billion in assets; the Joint Committee on Taxation estimates that this would raise approximately $100 billion in revenue over a decade.

- Increase corporate tax rate to 35% on both foreign and domestic earnings ($1.65 trillion); increase taxes on capital expenditures ($1.25 trillion). Warren previously proposed repealing the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, which lowered the corporate tax rate to 21%. The Warren health care plan supplements this tax increase by applying a minimum 35% tax rate to all income from U.S. corporations, whether they were earned domestically or abroad. University of California economists Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman believe that this policy could increase revenue from 2020–2029 by between $1.38 and $2.06 trillion; the advisers adopted $1.65 trillion as their estimate. Furthermore, the Warren plan raises taxes on capital expenditures, by requiring to deduct the cost of these expenditures over time, rather than at the time of purchase. The tax would fall most heavily on capital-intensive industries, such as manufacturing. The advisors estimate that this proposal and related features would raise $1.25 trillion from 2020–2029, “assuming that revenues from these provisions grow at the same rate as GDP.”

- Assess a 3% wealth surtax on billionaires ($1 trillion); tax unrealized capital gains ($2 trillion). Warren previously proposed assessing a 2% tax on Americans with net worth above $50 million, and a 1% surtax on those with net worth above $1 billion. Warren’s health care plan adds a supplemental 3% wealth tax on those with net worth exceeding $1 billion; i.e., in total, those with net worth of $1 billion or more would see 6 percent of their wealth taxed each year. The Warren advisers believe that this would generate $1 trillion in revenue from 2020–2029. In addition, Warren proposes to assess taxes on unrealized capital gains “for those households in the top 1%”; i.e., households with income exceeding $450,000. For example, a homeowning couple in the top bracket whose home increased in value by $50,000 would pay a 39.6% tax, or $19,800, even if the couple did not sell its home. Based on estimates by Lily Batchelder and David Kamin of the New York University School of Law, the Warren advisors believe this tax could yield $2 trillion between 2020 and 2029.

- Eliminate tax waste, fraud, and abuse ($2.3 trillion). The Warren advisors believe that by increasing IRS funding and enforcement, and increasing reporting requirements, the Treasury Department can obtain $2.3 trillion in taxes it believes it is owed but not currently collecting. The IRS estimates that there is a 15% gap between what it is owed and what it collects; the Warren proposal aims to bring that gap down to 10%.

- Enact the “Gang of Eight” immigration bill ($400 billion). Warren proposes helping to finance her health care plan by passing the Border Security, Economic Opportunity, and Immigration Modernization Act of 2013, which the Congressional Budget Office estimated would reduce the deficit by $175 billion between 2014–2023. Building on these estimates and moving them forward, the Warren advisers believe that the 2013 bill would raise $400 billion in tax revenues from 2020–2029, primarily because formerly illegal immigrants would now pay income and payroll taxes.

Warren’s rosy scenarios

Warren’s policy advisers are overly optimistic about her health plan’s fiscal performance in three basic ways. First, the plan assumes that its transformational approach to tax policy would not lead to meaningful changes in behavior among those with increased tax liabilities. Second, the plan assumes that raising taxes by $20 trillion over ten years will have no effect on economic growth, and thereby on overall tax revenue. Third, the plan does not account for the impact of “free” health care on demand for health care services, whether for valid medical reasons or due to waste, fraud, and abuse.

- Negative impact on employment and economic growth. Several of Warren’s proposed tax increases would have a substantial impact on economic growth. In particular, increasing the top corporate tax rate from 21% to 35%, and increasing taxes on businesses’ capital expenditures would have a meaningful effect on employment and economic growth, especially in the manufacturing sector and other capital-intensive industries. Furthermore, the abolition of the private insurance industry would lead to the loss of over 800,000 jobs among those directly or indirectly employed by health insurers or as health insurance brokers. All in all, we expect GDP growth to decrease by between 1.0 and 1.5 percentage points in the 2020–2029 period. The compounding effect of this slower growth would lead U.S. economic output to be 12.5% smaller in 2029 than it would be under current law, reducing federal tax revenues by $3.3 trillion over the ten-year period. Reduced employment would also lead to lower revenues from Warren’s payroll tax, which is assessed on a per-employee basis (we estimate this would have a negative $613 billion impact on tax revenues).

- Behavioral modifications in response to tax increases. The transformative and historic nature of Warren’s proposed tax increases would have substantial impacts on the behavior of businesses and individuals. Tax hikes on capital expenditures will lead to less capital investment. Dramatically increasing the corporate tax rate will lead to inversions and other efforts to re-domicile U.S. companies elsewhere. The Warren advisors predict a 15% avoidance rate for Warren’s wealth surtax; a 25% avoidance rate decreases the yield of the tax by about half. Some experts, such as Obama Treasury Secretary Larry Summers, consider 25% a conservative estimate, given the skill and resources of wealthy individuals to identify asset classes and other vehicles that fall outside of the wealth tax’s specifications. In addition, as Megan McArdle notes, an annual 6% wealth tax on billionaires would halve their net worth within a decade, reducing the future yield of the wealth tax, even if those billionaires did nothing to shield their assets. As Philip Klein has noted, the Congressional Budget Office has estimated that increasing the IRS enforcement budget by 35% will only yield $35 billion in net revenue over a decade. Finally, we are highly skeptical that taxing unrealized capital gains will yield additional tax revenues, because the policy will sharply reduce the demand for taxable U.S. assets, reducing their value.

- Increased demand for health care services, and increased waste, fraud, and abuse. The Warren plan will substantially increase the utilization of health care services for two reasons. First, by barring any form of patient cost-sharing in the form of premiums, co-pays, deductibles, or co-insurance, patients will have an incentive to utilize health care services far more frequently than they do today. The Urban Institute model accounts for a modest increase in utilization, driven largely by the expansion of coverage to the uninsured and undocumented immigrants. If utilization increases by another 10% due to patient demand, federal health care spending would increase by $3.5 trillion from 2020–2029. Furthermore, the Warren plan deliberately reduces administrative oversight of the Medicare program as a “cost-saving” measure. But reducing administrative oversight will lead to a considerable amount of waste, fraud, and abuse. The federal government estimates that approximately 10.5% of Medicare and Medicaid spending is improper; if replacing private insurers with Medicare leads to a 9% rate of improper payments, this would lead to an increase in federal spending of $3.1 trillion from 2020–2029.

The myth of Medicare’s low administrative costs

Advocates of single-payer health care often argue that Medicare has lower administrative costs than private insurance, and that Medicare is therefore more cost-effective. For example, the Medicare Trustees estimate that the Medicare Parts A and B spend between $2.30 on overhead for every $100 in spending on health care, for an administrative cost ratio of 2.3%. In general, the administrative cost ratio for private insurance is higher. For example, in 2016, the administrative cost ratios for private insurance in the individual market, small group market, and large group market were 7.1%, 13.9%, and 9.7%, respectively.

This comparison is highly flawed, because those enrolled in Medicare today are almost entirely over 65, with far higher average health care consumption than those under 65 enrolled in private insurance. In other words, the denominator in Medicare is far larger than for non-elderly private insurance, distorting what Medicare’s actual overhead costs are.

The comparison is also problematic because it fails to take into account the utility of administrative costs. Administrative costs are not inherently wasteful; indeed, insurers invest in administration in order to limit waste, fraud, and abuse in insurance claims. If Medicare had no administrative costs, for example, that would mean that bad actors could bill Medicare (and therefore, the taxpayer) for wasteful, fraudulent, or abusive medical spending.

A fairer comparison would be between traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage plans: private insurance plans that offer the same benefits as traditional Medicare, and to the same population. Medicare Advantage HMO plans deliver the traditional Medicare benefit but at 10% lower cost, despite the fact that Medicare Advantage plans have higher administrative costs. In 2017, Medicare Advantage plans had an administrative cost ratio of 4.5%, compared to 2.3% for traditional, fee-for-service, government-run Medicare plans.

Put simply: In Medicare, private plans with higher administrative costs are more cost-effective, overall, than government-run plans with lower administrative costs. The Urban Institute researchers account for this in their modeling, by assuming that a single-payer health care plan would require administrative cots of 6%. As the Urban researchers noted in their report,

We believe 3 percent administrative costs would be insufficient to carry out necessary tasks under a single-payer program. Because a single-payer approach exposes the federal budget to greater financial risks than other reforms, processes to prevent fraud and abuse and programs to manage care and monitor quality and access under centralized provider rates will be even more important than they are today.

Despite this warning, Sen. Warren’s advisors set administrative costs for their plan at 2.3%. “We thought we were being pretty aggressive in the assumptions we are making in terms of lowering the cost of the program over time,” said Urban Institute economist Linda Blumberg in The Atlantic. “They were clearly more aggressive.”

Conclusion

As noted above, we have restricted our assessment of Warren’s plan to its fiscal performance. We have not directly evaluated its non-fiscal features; however, the non-fiscal aspects of Warren’s plan could have extremely disruptive consequences to the U.S. economy.

From 2020–2029, the Joint Committee on Taxation estimates that the U.S. government will collect $45.6 trillion in tax revenues. We estimate that Warren plan would collect $12.1 trillion in additional revenue, increasing the total national tax burden by 27%. By her advisors’ estimates, the Warren proposal would increase tax revenue from 2020–29 by $21.1 trillion, an increase of 46%.

The Warren plan faces obvious political hurdles to its passage and enactment. In addition, some of its core provisions may not survive a constitutional challenge. In particular, Article I, Section 9 of the Constitution states that “no Capitation, or other direct, Tax shall be laid, unless in Proportion to the Census or enumeration herein before directed to be taken.” The 16th Amendment modifies this clause by empowering Congress to “lay and collect taxes on incomes, from whatever source derived, without apportionment among the several States, and without regard to any census or enumeration.” Neither of these provisions is widely thought to enable a tax on wealth as opposed to income.

Nearly all other industrialized countries finance their universal health care systems through taxes on consumption, usually in the form of a value-added tax or VAT. Value-added taxes, however, are paid by nearly all residents, including the middle class; Sen. Warren promised that her plan would not raise taxes on the middle class. As a result, she was forced to develop a series of tax increases whose impact on the economy will be far harsher.

In addition, Sen. Warren promised to abolish the private insurance industry. While the abolition of private insurance excites those on the left who are highly skeptical of the value of the private sector, there are better and less disruptive ways to make health care in the United States universally affordable and accessible.

Americans have shown throughout their history that choice, competition, and innovation can make once-scarce services universal, inexpensive, and abundant. Sen. Warren would be well served if she had more confidence in the ability of American innovators to do the same in health care.