University-based research funding: an economic perspective

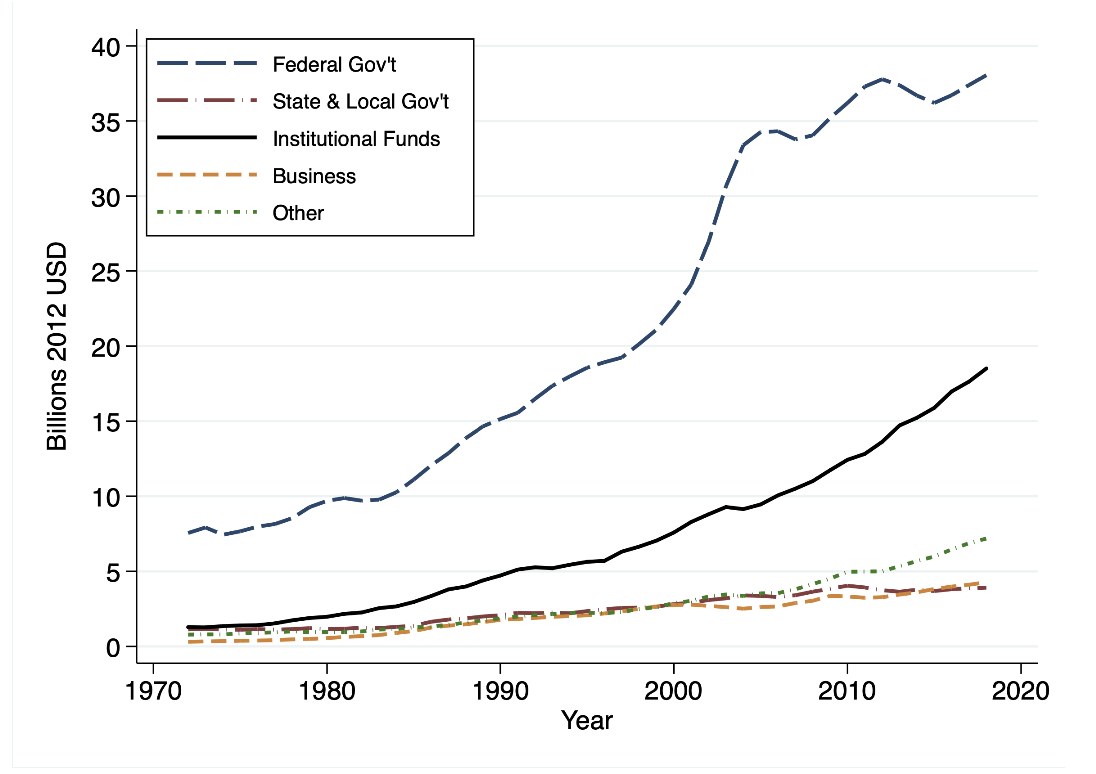

The federal government funds a considerable amount of research at universities. The below figure shows that about twice as much research at universities is funded by the federal government than by the institutions themselves. However, some of those funds pay for activities other than research, instead going to administrative support, facilities, and an ambiguous array of other overhead charges. Typically, those “indirect fees” are on the order of 30–50 percent of a typical federal research grant.

Recently, the National Institutes of Health decided to limit indirect rates to 15 percent. That action has led to some considerable divide between FREOPP scholars, with former dean of the Harvard Medical School Jeffrey Flier at odds with the perspectives of FREOPP founder and president Avik Roy and visiting fellow and Harvard Medical student Grant Rigney, who believe the spending cuts are a good idea.

Without taking a stance on whether or not the cuts are a good idea, I want to add a broader perspective which takes into account some of the economics of universities themselves rather than looking at research funding in isolation.

Universities are not just centers of learning or engines of innovation;they are both. In a forthcoming paper in American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, Titan Alon, Damien Capelle, and Kazushige Matsuda analyze the interplay between those two roles. Their research yields a surprising insight: university research spending, despite yielding very little in direct patent revenues, is a strategic tool used to boost educational quality and attract top students. This virtuous cycle—where research improves teaching, better teaching attracts high-ability students, and high-ability students help raise tuition—must play some role in how we think about any alteration to federal funding for research.

At the core of the model is the idea that research spending builds “intangible capital”—a mix of reputation, cutting-edge knowledge, and research capacity—that enhances educational quality and signals excellence to prospective students. In a fixed, zero-sum market for high-ability students, universities compete for a limited share of top talent, and stronger research spending leads to a higher quality signal that attracts more prized students and justifies premium tuition. This creates a virtuous cycle where robust research investments drive better education, which in turn fuels further research funding.

Federal research grants from agencies like the NIH cover both direct costs (equipment, salaries) and indirect costs (overhead). While these overhead funds are vital for covering administrative support, facility maintenance, and infrastructure—and serve as flexible resources to bolster research—they also tend to crowd-out internal spending, meaning universities often substitute some of their own funds with recovered overhead. Consequently, if a policy reduced the allowable overhead, the total drop in research spending might be less than one-to-one, as universities could adjust by reallocating more internal funds; however, the ease of this adjustment varies widely across institutions.

Now, consider a proposed reform where the government mandates that the overhead recovery on federal research grants be capped at 15 percent instead of the current 60 percent. Under this policy, the direct research funds remain unchanged, but the additional indirect funds shrink dramatically. For instance, on a $100 grant, instead of receiving an extra $60 in overhead (totaling $160), a university would only receive $15 extra (totaling $115). At first glance, one might worry that this would hurt all universities uniformly by reducing research funding. However, the broader competition among universities tells a more nuanced story.

Because universities already crowd out some of their internal research spending when they receive high overhead recovery, the net reduction in total research spending might be smaller than the drop in overhead suggests. Yet, the ability to substitute lost overhead funds is not equal across the board. Elite universities—those that are already top performers in research and have diversified revenue streams such as large endowments or additional grants—are better equipped to replace the lost overhead with their own resources. These institutions can maintain, or even improve, their research capacity, thereby preserving their strong quality signals.

In contrast, lower-ranked institutions that rely heavily on overhead to fund their research will struggle more to make up the shortfall. With a reduced capacity to invest in research, these schools will see their quality signals weaken, making them less competitive in attracting top students. Since the “pie” of high-ability students is fixed, the relative attractiveness of elite universities would increase even further. More high-ability students would then concentrate at the top schools, intensifying the competitive advantages of those institutions and pushing lower-tier schools further down the hierarchy. The end result is a higher degree of stratification and sorting between universities.

In the broader market for higher education, these adjustments have significant equilibrium effects. The overall level of research spending might not fall dramatically because universities can partially substitute internal funds for lost overhead. However, the distribution of research spending—and consequently the quality signals—would shift markedly. The competitive landscape would become more stratified, with elite institutions capturing an even larger share of the fixed pool of top students. This reallocation strengthens the virtuous cycle at the top: better research leads to better students, which in turn reinforces superior research capabilities and higher tuition revenues.

Over the long run, such a shift could have far-reaching consequences. Concentrating research funding among a few elite institutions might lead to more innovative research as the best researchers become even more concentrated, leading to stronger agglomeration effects.

While capping federal overhead at 15 percent might be seen as a move toward efficiency, the general equilibrium effects in the higher education market would likely result in increased stratification. The reform would reduce the flexible internal funds that many universities use to support research, but top-tier schools would be better positioned to absorb the loss and even strengthen their competitive advantage, allowing them to attract better researchers and students, and charge higher tuition. With the fixed pie of high-ability students, the gap between elite and lower-ranked institutions would widen, reinforcing the virtuous cycle of quality and innovation at the top.

">

">