When the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was signed into law in 2010, much of the attention focused on its historic expansions of coverage and insurance market reforms. But tucked inside the legislation was a lesser-known provision—Section 6001—that dramatically reshaped the hospital marketplace by effectively banning new physician-owned hospitals and freezing expansion of those already in existence. The law amended the Stark self-referral statute, prohibiting physician-owned hospitals from participating in Medicare if they were created after March 23, 2010, and placing strict limits on how existing physician-owned facilities could add beds, operating rooms, or procedure suites. Recently, however, legislation has been introduced to create an exemption to the ACA’s ban. The Physician-Led and Rural Access to Quality Care Act, H.R. 2191 would permit physician ownership of hospitals as long as it is more than a 35-mile drive from a main patient campus or critical-access hospital. This proposal is a step forward in reducing costs and improving patient access, but Congress can and should do more.

At the time of ACA’s passage, policymakers feared that allowing doctors to own hospitals would distort medical decisionmaking. They worried that physician owners would have incentives to refer patients to their own facilities, potentially leading to overutilization of services, inflated costs for Medicare and private insurers, and unfair competition with community hospitals. Concerns also included the possibility that physician-owned hospitals would cherry-pick hcathier, well-insured patients, leaving traditional hospitals with a disproportionate share of the sickest and poorest patients, threatening their financial stability. The ACA’s prohibition was, in short, a preemptive strike against what lawmakers saw as a looming two-tiered system of care.

These concerns were not without merit. Analyses from the Government Accountability Office and the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission showed that physician-owned specialty hospitals tended to treat a smaller share of Medicaid and medically complex patients than community hospitals. Critics argued that this selective patient mix allowed them to perform better financially, while leaving community hospitals with the burden of covering emergency departments, trauma services, and less profitable lines of care. In theory, physician ownership might also create a conflict of interest in clinical decisio-making, encouraging unnecessary admissions or procedures.

Yet, more than a decade later, the accumulated evidence tells a more complicated—and far more favorable—story about physician-owned hospitals. Multiple studies, including peer-reviewed analyses of Medicare data, have found that physician-owned hospitals frequently deliver care at lower cost per episode, achieve equal or better outcomes on key quality measures, and report higher patient satisfaction. For example, a 2019 study in The Spine Journal examining Medicare episodes for lumbar fusions found that physician-owned hospitals had lower complication rates and lower overall costs compared to non-physician-owned counterparts. Far from undermining patient care, physician ownership often appears to create stronger incentives for efficiency and accountability.

At the same time, the ACA’s prohibition has contributed to a broader problem: the rapid consolidation of the hospital sector. Large hospital systems have grown even larger, often through mergers and acquisitions that reduce competition in local markets. A consistent body of research, including a 2020 RAND analysis of commercial negotiated price data and a 2015 study, have demonstrated that greater hospital concentration is strongly associated with higher prices for private payers, without any corresponding improvement in patient outcomes. In many parts of the country, hospital systems now exercise near-monopoly power, enabling them to raise facility fees and negotiate higher reimbursement rates that drive up premiums and out-of-pocket costs. In this environment, the prohibition on physician-owned hospitals has functioned less as a safeguard against abuse and more as a barrier to competition that entrenches the dominance of large systems.

Repealing the ban would bring important benefits. First, allowing new physician-owned hospitals would restore a measure of competition in highly concentrated markets, creating downward pressure on prices. Physician-owned facilities tend to operate with lower overhead than sprawling hospital systems and can deliver procedures at a lower cost. This competitive discipline is badly needed at a time when Americans consistently rank hospital care as one of the most expensive components of their medical bills. Moreover, reforms such as site-neutral payment—which would prevent hospital systems from charging higher rates simply because a service is delivered in a hospital-owned outpatient department—could work hand-in-hand with physician-owned hospitals to level the playing field and reduce spending across Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance.

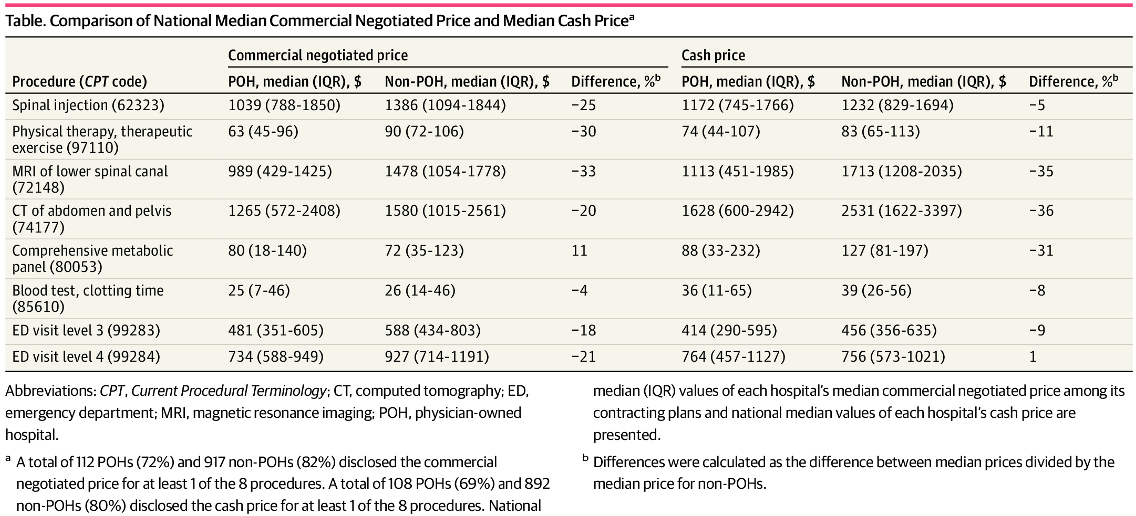

Comparison of National Median Commercial Negotiated Price and Median Cash PriceaAbbreviations: CPT, Current Procedural Terminology; CT, computed tomography; ED, emergency department; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; POH, physician-owned hospital. Table source: JAMA

Physician ownership also can enhance quality and patient experience. When doctors have a direct stake in the facilities where they practice, they have greater control over clinical workflows, staffing, and investment decisions. This often translates into more streamlined operations, shorter wait times, and closer attention to patient satisfaction. CMS’s hospital star quality ratings and the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems survey have frequently shown higher scores among physician-owned hospitals. While critics point to studies suggesting physician-owned hospitals sometimes report on fewer quality measures, the appropriate solution is to strengthen reporting requirements and ensure transparency across all hospitals, not to prohibit an entire class of facilities. With standardized quality metrics, patients can make informed choices, and physician-owned hospitals can compete fairly on the basis of outcomes rather than assumptions.

Third, the concern about self-referral can be addressed without resorting to a blanket ban. The Stark Law and the federal Anti-Kickback statute already prohibit improper financial relationships and referrals. Section 6001 included disclosure and anti-steering provisions for existing physician-owned hospitals. Policymakers could strengthen these safeguards with modernized enforcement tools, such as real-time monitoring of referral patterns, enhanced ownership disclosure requirements at the point of care, and more severe penalties for violations.

Perhaps most important, reversing the ban could bring significant benefits to low-income Americans. Low-income patients are disproportionately harmed by hospital consolidation, which leads to higher prices, fewer options, and reduced service availability in underserved areas. Many community hospitals have closed maternity wards, trauma centers, or other essential services due to financial strain, leaving patients with long travel times and limited access. By enabling physicians to open new facilities, especially in rural or low-income urban areas where large systems may not invest, policymakers could expand capacity, reduce wait times, and create more affordable care options. With the right safeguards—such as requiring physician-owned hospitals to meet minimum thresholds for treating Medicaid and dual-eligible patients—these facilities can help fill critical gaps in the safety net.

The ACA’s prohibition on physician-owned hospitals was rooted in caution, but its practical effect has been to protect incumbent hospital systems from competition at the expense of patients. A decade of experience has shown that physician-owned hospitals can deliver lower costs, equal or better quality, and higher patient satisfaction, while existing laws provide adequate tools to guard against abuse. It is time to replace the blanket ban with a smarter framework—one that allows physicians to establish hospitals, requires rigorous transparency and accountability, and ensures equitable access for vulnerable populations. By doing so, policymakers can foster competition, expand capacity, and deliver meaningful relief to patients, especially those struggling the most with the high cost of American health care.