“People should ultimately be financially better off by working and earning more money. Putting workers in a position where a raise could mean losing the ability to afford a rent payment is not a situation anyone should have to face.”–Iowans for Tax Relief

Executive Summary

Iowa’s existing social welfare system does a reasonably good job of dealing with material deprivation. By providing income, food, shelter, health care, and other benefits, it successfully makes poverty somewhat less miserable. However, it is far less successful in helping people escape poverty and become self-sufficient.

One reason for this failure is that too many welfare programs can discourage recipients from working, marrying, or taking other steps to improve their long-term prospects.

Obviously, policymakers do not want social welfare programs to reduce work. Unfortunately, that is exactly what happens when recipients face so-called “benefit cliffs.” People are less inclined to work when they can earn more by not working. A few smart policy choices can ensure benefits help people in need without trapping them in dependency.

Social welfare programs should provide temporary assistance while encouraging long-term self-sufficiency. However, certain aspects of current programs discourage work or career advancement.

The highest marginal tax rates in America are not faced by millionaires or billionaires, but by people leaving welfare for work. As welfare recipients earn more income, they face the benefit cliff. The combination of lost benefits, payroll taxes, and new job-related expenses reduces the value of non-welfare income. It can sometimes leave those returning to the workforce worse-off financially in the short term.

Thus, even though work is the key to long-term self-sufficiency, the current structure of many welfare programs often discourages work in the immediate term and leaves families trapped in dependency.

Since 2021, 25 states and the District of Columbia have passed legislation addressing welfare cliffs. Most of these have simply set up studies or commissions, but a few have attempted systemic reforms. There have generally been three strategies: 1) raising eligibility levels and reducing phaseouts so that the cliff occurs much farther up the income scale; 2) decreasing benefits overall; and/or 3) making work a mandatory requirement for receiving benefits. For different reasons, none of these approaches has proven satisfactory.

A better approach would be to establish “transitional benefits” to offset the loss in benefits that occurs as a recipient earns non-welfare income. Rather than immediately losing benefits when an individual’s income reaches the eligibility threshold, benefits would be “stepped down” in proportion to increases in non-welfare income. Doing so would reduce the impact of welfare cliffs, but unlike a general increase in eligibility, it would not draw large numbers of new recipients into the system.

By establishing transitional benefits, Iowa can smooth the transition from welfare to work, leading to more earnings, more self-sufficiency, more innovation, and more efficiently spent welfare dollars.

Work, poverty, and welfare

Although the exact number fluctuates yearly, the federal government funds more than 130 separate anti‐poverty programs. Some 70 of these provide cash or in‐kind benefits to individuals, while the remainder target specific groups, such as the Community Development Block Grant.

Altogether, the federal government spent more than $1.1 trillion on welfare programs in 2021. State and local governments added about $862 billion in additional funding. Thus, governments at all levels are spending nearly $2 trillion per year to fight poverty, not counting payments related to COVID-19. Stretching back to 1965, when President Lyndon Johnson first declared his War on Poverty, anti‐poverty spending has totaled more than $30 trillion.

Yet the results of all this spending have been disappointing. Welfare payments have helped reduced poverty rates, but some studies suggest that most of the improvement took place in the welfare programs’ early years, and that the marginal gains of recent additional spending have been minimal.

The goal of welfare programs should be to both provide immediate assistance for basic needs and to enable recipients to escape poverty through self-sufficiency over the long run. Too many federal and state welfare programs seem perversely designed to work against the overarching goal of enabling Americans to not just endure poverty more comfortably, but to escape it altogether.

Work is an important component of the road to self-sufficiency, as the evidence overwhelmingly suggests. Just 4.1 percent of those working full time live in poverty. Even a part-time job makes a big difference; roughly 10 percent of part-time workers live in poverty.

Isabel Sawhill and Ron Haskins of the Brookings Institution concluded that, among many factors, increasing work rates had the greatest effect in reducing poverty. Likewise, a study for the University of California’s Center for Poverty Research found that “individual weeks worked and aggregate wage levels are the important predictors of how many escape or avoid poverty from one year to the next.” Another Brookings study determined that most people are poor in the United States because they either do not work or work too few hours to move themselves and their children out of poverty. More specifically, the heads of poor families with children worked only one half as many hours, on average, as the heads of non-poor families with children.” As a study by Regina Baker for the Journal of Marriage and Family found, the importance of work as a route out of poverty has been increasing in recent years, even as other traditional escapes from poverty such as marriage have been declining in importance.

In the end, work is fundamental for an individual to be truly independent and in control of their own financial futures—and to further the best interests of their families.

Work is perhaps the most important anti-poverty tool, but evidence also suggests that encouraging work has a larger impact on poor communities. There are substantial peer effects that lead to greater work participation and poverty reduction generally. As the Senate Joint Economic Committee has noted, “At the community level, the disappearance of work can lead to depopulation, brain drain, and the decline of other institutions of civil society.” And, of course, more people working means greater overall economic growth, tax revenue, and entrepreneurship.

Studies also show that work provides a variety of positive benefits. It increases self-esteem and a sense of purpose, helps individuals form a community, and exposes them to new experiences. In short, work benefits Americans individually and collectively.

There is also an intergenerational aspect to work. For example, one study by Joseph Altonji and Thomas Dunn for the Journal of Human Resources found that children tend to work the same number of hours as their parents, and that only part of this tendency can be accounted for by local labor conditions. The authors conclude that parents pass on their preferences for work hours either through modeled behavior or other factors. An Australian study reached a similar conclusion, finding a stronger work ethic in children from poor families in which the mother worked. The authors write, “young people’s attitudes toward work and welfare are shaped by socialization within their families.” Another study, by Jens Ludwig and Susan Mayer of the University of Chicago, found that if all eighth graders lived in a household with at least one working adult, poverty in the children’s generation would drop by as much as seven percent.

Work also can provide significant non-financial benefits. Prime-age men who are disconnected from the labor force lose economic independence, but also the respect of others and self-assurance associated with it. Survey data shows that disconnected men are less satisfied, less happy, more stressed, and more depressed than their employed counterparts.

Simply having a job, of course, does not guarantee a route out of poverty, as many working Americans remain poor. Still, most policymakers would agree that a successful anti-poverty strategy should encourage work. Unfortunately, many current social welfare programs fail to do so.

The American welfare system encourages people to leave welfare for work. It certainly shouldn’t erect barriers to work. One of the most significant of these barriers is the extremely high marginal tax rate that the current welfare system imposes on work.

Marginal tax rates and work incentives

Policymakers pay a great deal of attention to the impact of marginal tax rates on businesses and higher earning individuals. But perhaps more important, marginal tax rates impose a burden on low-wage Americans who receive benefits through social welfare programs.

For present purposes, the marginal tax rate is defined as the percentage of an additional dollar of earnings that an individual can’t use because it’s offset by taxes or reduced government benefits.

“When marginal tax rates are high, people tend to respond to the smaller financial gain from employment by working fewer hours, altering the intensity of their work, or not working at all,” as the Congressional Budget Office has noted.

Most welfare programs are designed so that benefits phase out as a recipient’s income from work increases. On the surface, this seems entirely reasonable because benefits ought to be directed to those who need them most. Welfare programs should target low-income families, not the middle class. At the same time, however, the phaseout of benefits can harm recipients when the shift is large enough that a small increase in employment income can cost a worker thousands of dollars in lost benefits and services.

The cliff’s impact on work effort is initially small. The payroll tax kicks in with the first dollar earned—though it may eventually be recouped through the Earned Income Tax Credit—but benefit reductions phase-in, becoming more substantial as the recipient’s earnings increase.

According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), for households with children, marginal tax rates are highest for families with income just above the poverty line. This comports with a number of studies showing the largest impact of such high marginal tax rates falling on those earning between 100 and 250 percent of the federal poverty level. Thus, the cliff may not discourage a beneficiary from taking a job, but marginal tax rates may create a disincentive to accepting a promotion or moving from part-time to full-time work. HHS also concludes that low-income families with children face higher marginal tax rates than those without children.

The figures below illustrate how welfare cliffs work. As an individual begins to earn employment income, their total resources increase correspondingly since they are now receiving income from both work and welfare. Eventually, however, the amount of employment income reduces or eliminates their eligibility for welfare benefits, resulting in a sudden decline in available net resources. Using a tool from the Atlanta Fed, these charts assume a single mother of two children, aged 2 and 5, in Butler County, Missouri:

Figures 1 and 2

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta “Benefit Cliffs Across the U.S.” database

To understand what this means in practice, consider a mother with two children in Georgia who is receiving benefits from five different means-tested welfare programs: Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Medicaid, housing assistance, and childcare subsidies. If she earns $12.50 per hour from a full-time job, her combined income from both wages and welfare will total slightly more than $45,000 annually as a combination of both earnings and welfare benefits. Of course, she will pay some taxes on this amount and incur work-related expenses, but she will still be reasonably well-off financially. However, if she were to earn just $1.25 more per hour, she would lose so much in welfare benefits that her total net income would decline by nearly $15,000 per year.

Such a loss is hardly a unique situation. According to the Cardinal Institute, a 30-year-old mother of two in West Virginia, whose gross annual income increased from $29,444 to $29,944 would have her food assistance cut from $10,325 to just $1,445. Then, as her income increased from $45,994 to $46,494, she would lose all of her $12,227 in child care benefits. Similarly, prior to recent reforms, a single mother with two kids in the city of St. Louis who earned $27,001 instead of $27,000 lost nearly $9,300 in child care benefits alone. (See Appendix I for an example of how this might play out in Iowa.)

And, while most research has been focused on the labor effect of welfare cliffs, marriage can also create cliffs for many recipients. For example, a mother who marries the father of her children may lose a substantial portion of her benefits depending on her new spouse’s income.

Unmarried parents are better able to meet the income and asset eligibility tests for programs such as TANF and SNAP. For example, if a single mother with a net income of 125 percent of the federal poverty level marries someone with an income, it could push them over the threshold, and no one in the household would be eligible for SNAP. If they chose instead to cohabitate without marrying, the benefits would continue.

Finally, it should be noted that benefit cliffs can lead to increased dishonesty or fraud in the welfare system. Consumption data already suggests that many low-income Americans earn income that is not reported. Welfare cliffs almost certainly make this more likely, since welfare cliffs mean that the penalty for additional income can be so substantial, the incentive for concealing income is high.

Evidence suggests that if the recipient does not respond to the disincentives, they may end up better off in the long-term. That is why some scholars prefer the term “benefit desert” to “benefit cliff.” If an individual makes it through the desert and emerges on the other side, they will eventually find themselves better off. But that requires a significant degree of long-term thinking and willingness to endure short-term pain that is far from universal. In fact, long-term thinking becomes more difficult when an individual is facing immediate hardship or scarcity.

The research

The sprawling and byzantine nature of the U.S. welfare system can make marginal tax rates difficult to measure precisely. There are more than 70 federally funded programs that provide benefits to individuals. States also contribute funding to some of these programs and fund others in full. Eligibility for programs may be set by the federal government, by states, or by states within broad federal guidelines. As a result, different programs have different phase-out rates and therefore steeper or shallower cliffs. Moreover, because of the complexity and difficulties in maneuvering through the application and eligibility process, similarly situated recipients often receive very different baskets of benefits. And, since relatively few families on welfare receive benefits from just a single program, they may encounter not just a single welfare cliff but multiple cliffs often with a compounding impact.

Most observers suggest that programs such as TANF, housing vouchers, and child care subsidies generally have the steepest cliffs, while the EITC has a relatively small one. Other programs such as SNAP and Medicaid fall somewhere in between. Medicaid can be particularly complex because of the interaction between it and subsidies under the Affordable Care Act. Therefore, the assumptions and methodological choices made by researchers can often lead to differing results. But those differences are more often a matter of degree than direction.

Welfare recipients’ marginal tax rates can be astoundingly high. As the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta warns, “these benefit cliffs can be so severe that low-income workers may be temporarily better off financially by not advancing to take a higher-paying job.”

Several studies have documented this, including:

- A 2012 Congressional Budget Office report looking at Pennsylvania found that marginal tax rates, after accounting for the loss of benefits, could reach extremely high levels, discouraging both labor‐force entry and increasing work hours. The report found that unemployed single taxpayers with one child would face an effective marginal tax rate of 47 percent for taking a job paying the minimum wage in 2012, and if their earnings disqualified them from Medicaid, they could have faced an astonishing marginal tax rate of 95 percent.

- Likewise, an Urban Institute study by Elaine Maag and others found that a single parent with two children moving from no earnings to poverty‐level earnings would face a marginal tax rate as high as 25.5 percent in Hawaii.

- A 2014 Illinois Policy Institute study found that a single mother with two children in that state who increased her hourly earnings from the minimum wage of $8.25 to $12 would increase her net take‐home wage by less than $400 per year, or about 19 cents per hour. Even worse, if she further increased her earnings to $18 an hour, her annual net income would decrease by more than $24,800 due to benefit reductions and tax increases. Although inflation and policy changes over the last decade have changed some of these studies’ specifics, the general conclusions remain the same.

- Recent studies show similar results. A 2022 study of Forsyth County, North Carolina found marginal tax rates for welfare recipients ranged from 90-100 percent and concluded that “a rational individual would never work more than part-time, according to indifference curve theory.”

- Another study by Gizam Kosar and Robert Moffitt found that a single mother with two children, earning 100-150 percent of the poverty level and receiving Medicaid and SNAP, faced a shocking marginal tax rate of 81 percent.

- A study by the Urban Institute looking at families in Colorado, Minnesota, and New York reported different outcomes. For up to two-thirds of the representative families, they estimated the marginal tax rate for households that increased their annual income by $2,300 was about 50 percent.

- HHS calculates marginal tax rates for families with incomes under 200 percent of poverty as ranging from 20-59 percent. That is certainly less dramatic than the 100 percent or more found in other studies, but it still represents a substantial bite. Moreover, as the study notes, it is not always a purely financial question. The loss of benefits, even if net income increases, can leave former recipients feeling less stable and secure.

Scholars disagree about how many recipients actually encounter welfare cliffs. As noted above, the cliff is most likely to affect those earning 100-250 percent of the poverty level. That level of income would mean a full-time job at more than minimum wage. However, many welfare recipients lack the skills to earn that amount. Scholars with the Foundation for Government Accountability estimate that just two percent of welfare recipients change their behavior because of welfare cliffs. This seems unrealistically low and is a clear outlier in the research. For instance, a study by David Altig and others for the National Bureau for Economic Research, estimates that at least one quarter of low-income workers will face a lifetime marginal tax rate of 70 percent or more. Notably, this is a significantly higher marginal rate than the median lifetime marginal rate paid by the top one percent of earners (50 percent) and all other workers (42 percent).

Several studies have shown that welfare recipients are, in fact, “highly sensitive to the triggers that cause changes in government assistance structures.” Welfare recipients may not know the precise marginal tax rate they will encounter for each new dollar of income, but they have a general understanding that, at some point, increasing their outside income does not leave them as well off as it should. Indeed, the Congressional Budget Office found that low-income workers responded more to wage changes than higher income workers. Moreover, recipients were more likely to reduce their working time when their income loss was framed in terms of benefit loss rather than taxation.

- In a survey of Tennessee welfare recipients 90 percent said that if they had financial assistance that would help them through a cliff, they would take a better-paying job even if it meant losing their benefits. Nearly 80 percent said that they would work more hours, 77 percent said that they would take a raise, and 69 percent said that they would pursue additional education opportunities.

- A study by Susan Roll and Jean East in the Journal of Poverty found that, in Colorado, 34 percent of welfare recipients make work decisions specifically based on the need to avoid welfare cliffs. Some recipients were willing to turn down up to 12 hours of additional work weekly to avoid the cliff. A second Colorado study, evaluating a child care pilot program, also found that program’s effectiveness was limited by fear of the cliff effect. Most program participants acknowledged that they were concerned about a loss of benefits due to even a slight change in income. The evaluation concluded that “reducing worry about the cliff effect could spur positive action toward increasing income by working more hours, taking a new job, or accepting a promotion.”

- A 2017 Maryland study concluded that a family’s prospects for economic success are likely to be limited if they face barriers to wage progression, and they identified the welfare cliff as one of those barriers. And another study found that mothers receiving child care subsidies decreased their work hours as their wages increased compared to mothers who did not receive subsidies, suggesting that fear of losing benefits reduced work effort.

- Results from five focus groups in Connecticut found that roughly one third of participants had intentionally reduced their earnings to avoid a benefit cliff, either by restricting hours worked or declining potential raises.

- A 2019 survey of Ohio businesses found that “nearly one in five had experienced issues in some way with hiring, promoting, or increasing wages for their employees due to concerns that increased income would result in losing some form of public assistance.”

- A similar survey of Florida employers found that a third of businesses reported employees declined a raise or increase in work hours because they feared a loss of benefits.

- In Alabama, more than a third of survey respondents had turned down a job or promotion due to benefits cliff threats.

This is important for employers and economic growth generally because, as the Aspen Institute points out:

Employees who are able to experience economic security for their children when accepting raises, working additional hours, or advancing in their careers have a greater likelihood of worker retention. Particularly in times of low unemployment, there is an added benefit to employers who are better able to maintain and promote talent.

As Atlanta Fed director David Altig writes, the evidence is overwhelming that benefit cliffs are “a disincentive for people to come to work if they are out of the labor force. It’s a disincentive for them to work more if they are in the labor force. And it is very much a disincentive for them to skill up and invest in their own economic mobility and resilience as a consequence of that.”

Low-income Americans are acting rationally and responding to the sometimes harsh incentives in the welfare system. If someone is paid more not to work than they can earn by working, they will be less inclined to work. After all, despite its many benefits, there is an opportunity cost to work. For example, it requires forgoing leisure activities, time with family, and other desirable pastimes. There are also new financial expenses such as transportation, clothing, child care, and so on. To encourage work, therefore, earnings should be large enough to more-than-offset such costs. Welfare cliffs make it harder to do so.

Attempts to address the welfare cliff

The disincentive effect of welfare cliffs is generally acknowledged across the political and ideological spectrum. But there is much greater disagreement on how to fix the problem. Moreover, the dual federal/state nature of the U.S. welfare system, as well as the wide variation in rules between states, means that a one-size fits all answer is unlikely to work. States have been experimenting with potential responses.

Since 2021, 25 states and the District of Columbia have passed legislation dealing with benefit cliffs. Most of these have involved studies or commissions, but a few have attempted systemic reforms to address the issue. There have generally been three strategies: 1) raising eligibility levels and reducing phaseouts so that the cliff occurs much farther up the income scale; 2) decreasing benefits overall; and/or 3) making work a mandatory requirement for receiving benefits. For different reasons, none of these approaches has proven satisfactory.

Raising Eligibility Limits: The most common response to benefit cliffs has been to increase eligibility levels and delay phaseouts so that the cliff occurs much higher up the income scale. The belief is that the cliff will have a reduced impact on those earning higher incomes overall. Some activists have suggested going even farther and establishing a universal basic income.

Iowa took this step with its child care subsidy in 2023.

However, for many welfare programs, eligibility already reaches into the middle class, a trend that has been growing in recent years. As Brookings scholars have shown, an increasing share of welfare expenditures goes to middle class recipients rather than those most in need. Only about 47 percent of means-tested welfare spending now goes to those with the lowest 20 percent of earnings.

In 1970, for example, more than 70 percent of Medicaid spending went to individuals in the lowest quintile of incomes. Today, less than half does. SNAP shows a similar, if less dramatic trend. The share of expenditures going to the lowest income quintile has fallen from 80 percent to 63 percent.

A general increase in eligibility, then, will likely be costly, draw new people into the system, and redirect funding from those who need assistance the most.

Benefit Cuts: The flipside of the benefits coin is to reduce benefits sufficiently to make work always preferable to not working. That is, if benefits are low enough, work will appear a better deal by comparison even considering potential cliffs. There is evidence that suggests work increases in the absence of welfare benefits or when benefits are lost.

However, a reduction in benefits would leave some recipients worse off. Those who cannot replace the lost income will likely face significant hardships. This would include the elderly, those with disabilities, single mothers with young children, and those living in areas with high unemployment. For this reason, there have been few legislative attempts to roll back eligibility levels.

Work Mandates: The most straightforward way to deal with the work disincentives in welfare programs is simply to require recipients to work. While work requirements have been imposed at the federal level, five states—California, Kansas, Ohio, Oregon, and Texas—have moved to strengthen such requirements for at least one program since 2021. Congress has also tightened work requirements for SNAP.

Most of the research to date on the effectiveness of work requirements has focused on cash welfare, the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program. Relatively little has been done to study the impact on programs like Medicaid and SNAP, and what has been done has yielded mixed results, with some showing a positive impact and others coming to the opposite conclusion.

Work requirements can also be costly to enforce and add yet another layer of complexity to an already labyrinthine welfare system. Imagine trying to navigate different work requirements for each of the more than 70 welfare programs that provide benefits to individuals.

The vast majority of employable adult welfare recipients work now, though it varies significantly by program. For example, roughly 70 percent of SNAP recipients are employed—51 percent of whom work full time—whereas just 17.5 percent of TANF recipients work full time. Of course, many of those receiving government assistance are not prime candidates for work. Roughly half of TANF beneficiaries are children, as are 36 percent of SNAP beneficiaries, and 46 percent of those receiving Medicaid benefits. But these numbers tell us little about the adults in those families who, while not technically beneficiaries of the program, receive benefits indirectly. Many other recipients are elderly or disabled.

Work requirements only impose a general requirement to work a certain number of hours, they do not deal with the disincentive to increase earnings beyond a certain level. Since the biggest effect of welfare cliffs hits a couple rungs up on the income ladder, a simple requirement that participants work is unlikely to change incentives. A recipient can always work enough to satisfy the work requirement, but still limit working hours or wages enough to avoid the cliff and subsequent loss of revenue.

In the end, none of these proposals is likely to provide an effective fix to the problem. A different approach is needed.

A Better Approach: Transitional Benefits

A potential solution to the benefit cliff problem is for states to provide transitional benefits that offsets all or part of the lost benefits. Rather than immediately losing benefits when an individual’s income reaches the eligibility threshold, benefits would be stepped down in proportion to increases in non-welfare income. Doing so would reduce the impact of welfare cliffs but, unlike a general increase in eligibility, would not draw large numbers of new recipients into the system. Several states are already experimenting with this approach.

Missouri: In 2023, Missouri enacted what may serve as a national model for dealing with welfare cliffs. Under the new law, Missouri would establish transitional benefits for those receiving benefits from SNAP and TANF. The law also makes permanent an existing transitional benefits for the child care subsidy program, eventually phasing out at 300 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL). Work requirements and other welfare restrictions would remain in place for the duration of the benefits, but the transitional benefits would not count against lifetime caps. The transitional benefits are not purely dollar for dollar, but would smooth the loss of benefits so that a recipient would lose no more than 20 percent of monthly benefits at each income tier.

Unfortunately, implementation of the new Missouri law has been slow going. A combination of upfront costs, legal interactions between federal and other state welfare laws, and footdragging by the state’s welfare bureaucracy has meant that no one has received transitional benefits as of July 2024. All that can be said for certain, therefore, the Missouri approach is theoretically promising, but verifiable results will not be known for some time.

Tennessee: A transitional benefit is also available as part of Tennessee’s OurChanceTN pilot program. The pilot is funded through surplus TANF funds that Tennessee has accrued. Participants must have at least four dependents under age 18, earn less than $55,000 per year, and currently receive benefits from at least one welfare program. The transitional benefits can be used to cover health care, housing, and child care, with payments made directly to providers and approved on an individual basis. Roughly 500 Tennesseans participate in the pilot. The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta is monitoring the results.

Massachusetts: Massachusetts is implementing a $1 million pilot project that taps unused funds from the American Rescue Act to provide transitional benefits. The program calculates a participating family’s yearly financial resources, including earnings and public benefits. Participants thereafter receive cash payments to offset any net income loss as the family’s income slowly increases and benefits decrease. Roughly 100 families are participating.

District of Columbia: In 2023, Washington, D.C. launched a $17.7 million pilot project that includes efforts to reduce the effects of welfare cliffs. Roughly 600 families are participating in the program. Early results have been modest, with the percentage of recipients reported to be working rising from roughly 35 percent to 41 percent.

Pending Proposals: Connecticut, Maryland, and Ohio are also considering legislation to establish pilot programs. In addition, Florida is looking at whether to establish a small pilot for those in the foster care system.

Questions Remain

All of these programs are too recent to properly evaluate, but they raise obvious questions. For example, there are costs associated with paying transitional benefits, albeit less than an eligibility hike. In Missouri, for example, early estimates suggest transitional benefits would cost $270 million per year to start. In theory, transitional benefits would save money over the long haul as they encourage recipients to leave welfare for work. However, given past experience with predictions that spending $1 today will save $X in the future, states should be cautious about such claims. Of course, there are significant social benefits to encouraging work even if a transitional approach does not end up being a fiscal cost saver.

It is also possible that transitional benefits will not encourage more recipients to work. Participants may not understand how the transitional benefits affect them. There may be other factors keeping recipients from full labor force participation that have been misattributed to the cliff. And, of course, transitional benefits do not eliminate the cliff, as nothing short of a universal basic income would. Transitional benefits simply move the cliff further up the income scale, where the strain of lost benefits may be lessened. Depending on the design of the transitional program, the benefit level could still be too low to significantly change recipient behavior.

These questions should not prevent states from experimenting with transitional benefits. Welfare cliffs are self-evidently a problem, and the perfect shouldn’t be the enemy of the good. However, implementation should be accompanied by vigorous monitoring and evaluation.

Conclusion

Iowa’s existing social welfare system can actively discourage work, an important element for getting out of poverty. In particular, benefit phaseouts combined with taxes and costs of employment, can create a welfare cliff or desert, leaving individuals worse off if they take a job, accept a promotion, or increase their work hours. As a result, many families remain trapped on the dole for far longer than they should be.

Most efforts to deal with this problem so far have followed one of three strategies: 1) raising eligibility levels and reducing phaseouts so that the cliff occurs farther up the income scale; 2) decreasing benefits overall; and/or 3) making work a mandatory requirement for receiving benefits. Increasing eligibility is costly and draws more people into the welfare system. Cutting benefits can be cruel, leaving many struggling in poverty. Work requirements have some value, but the evidence suggests that they have reached the limits of their effectiveness.

Fortunately, however, there is another approach.

Ideally, Iowa should follow Missouri’s lead and establish transitional benefits that will help stabilize families as they try to work their way out of poverty and towards self-sufficiency. Rather than immediately losing benefits when an individual’s income reaches the eligibility threshold, benefits would be stepped down in proportion to increases in non-welfare income.

Both state governments and stakeholding organizations should rigorously track, monitor, and evaluate any transition programs, both pilots and program-wide efforts. As noted above, such efforts are new and questions remain. While there is strong reason to believe that transitional benefits will encourage work and other positive steps, hard data is scarce. Therefore, as programs move forward, they should undergo constant evaluation, and adjusted as necessary.

It is hard to deny the importance of work to any long-run strategy for reducing poverty. It is unfortunate, then, that many social welfare programs are designed in ways that discourage work. Welfare cliffs effectively penalize welfare recipients for taking exactly those steps toward self-sufficiency that policymakers desire. However, by establishing transitional benefits, Iowa will strengthen incentives for welfare recipients to work.

Appendix I

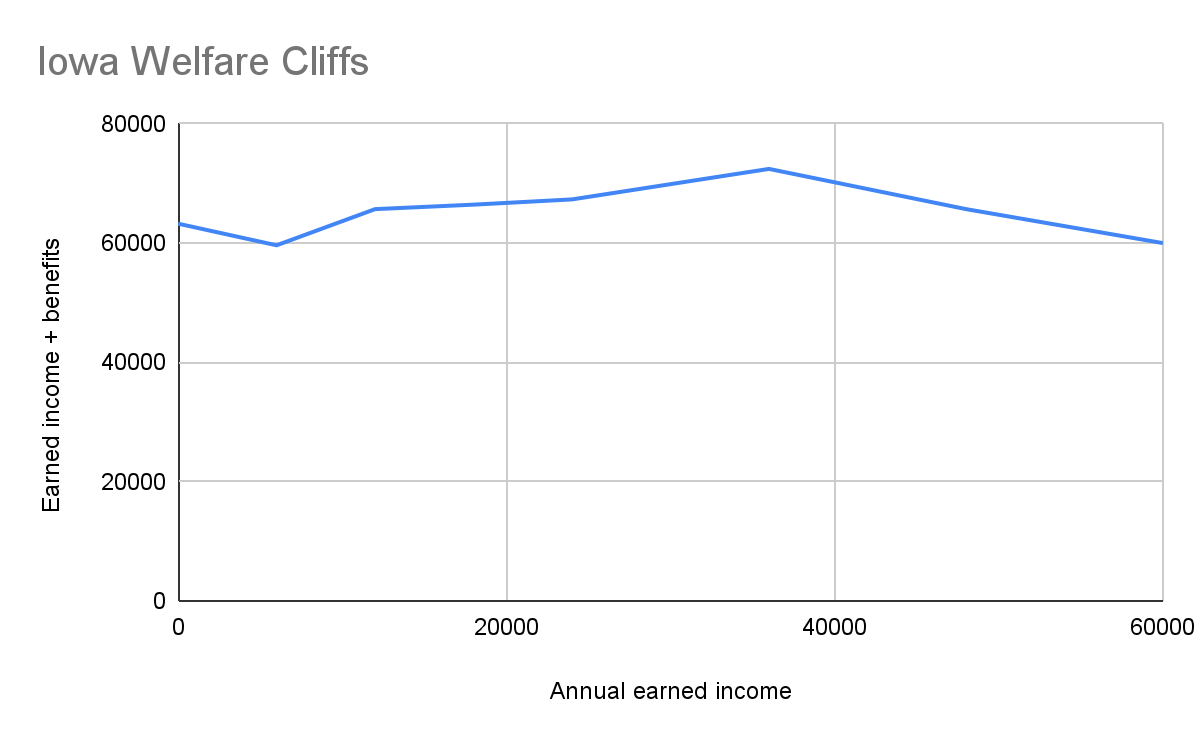

Iowa’s Welfare Cliffs

The impact of welfare cliffs varies considerably from state to state. So, what does it mean for welfare recipients in Iowa? To answer this question we look at the case of a hypothetical low-income mother with two children, a fairly typical family configuration for welfare recipients.

TANF: Such a family could receive a maximum of $498/month from the Family Investment Program, Iowa’s version of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) as long as their annual income is below $326/month ($3,915/year). At that point, TANF benefits begin to phase out, reaching zero at $1,000/month ($12,000/year).

SNAP: The family would likely also receive support through SNAP, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, a maximum benefit of $740/month. Eligibility for SNAP in Iowa is subject to a two pronged income test. First, the recipient’s gross income cannot exceed 130 percent of the federal poverty level , $2,693 per month or $32,316 annually for a family of three. Second, the household’s net income (after allowable deductions) cannot exceed 100 percent of the FPL, $2,072/month or $24,864/year. Benefits phase out as incomes increase. At an income of roughly $1000/month, the benefit would have fallen to $400 and would reach zero when the family’s gross income exceeds $1,918/month.

Medicaid: It is also extremely likely that our hypothetical family would receive health coverage through Medicaid. Determining the value of Medicaid benefits is difficult since the amount of benefit received is dependent on health. If a recipient never visits a health provider, the benefit received is in once sense zero, while for a recipient receiving significant amounts of care, the value would be extremely high. For purposes of this model, it is assumed that the benefit is equal to the average health insurance premium that the family would have to purchase in order to receive comparable benefits.

Eligibility for Medicaid is complex and based in part on the category of recipient. Children ages 18 or under are eligible if the family’s income is no more than 211 percent of the FPL ($4,144/month or $49,728/year). The mother would likewise be eligible if the family income was less than 138 percent of FPL. There are different eligibility categories for pregnant women, non-parental caregivers, and others. Medicaid generally does not provide partial benefits or have a phaseout. Eligibility is all-or-nothing based on meeting income thresholds. Families with incomes exceeding the permissible amount for each category will not qualify for benefits, making for an extreme cliff, although the family may become eligible for subsidies under the Affordable Care Act which could offset some of the loss.

Section 8 Housing Support: Housing benefits are less common, but it is possible that the family would receive benefits through the Section 8 Housing Choice Voucher Program. The maximum amount of rent that can be covered by Section 8 vouchers depends on the payment standards set by the local Public Housing Authority (PHA). As of 2024, the payment standard for a three-bedroom unit in Iowa County is approximately $1,943 per month. Eligibility for Section 8 housing vouchers in Iowa is determined by income limits based on the Area Median Income (AMI). To be eligible for a full voucher, the family income cannot exceed 30 percent of the AMI. That amount will vary from county to county and city to city but generally runs around $2,195/month ($26,340/year), which is what is used for purposes of this analysis. From that point on, the benefit phases out, reaching zero at 50 percent of AMI, roughly $3,658/month ($43,900 annually).

Child Care Subsidies: In 2023, Iowa increased the eligibility for child care subsidies to 160 percent of the federal poverty level or $39,720 for a family of three. Subsidies generally run 60-80 percent of market rates. The Legislative Services Agency estimates that to be about $461/month per child or $922 for our hypothetical family.

Earned Income Tax Credit: Assuming the mother earned at least $10,000/year, the family would be eligible for both the federal and state Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). The maximum EITC for a family with two children would be roughly $6,604. The state EITC is equal to 15 percent of the federal EITC received. The EITC begins slowly phasing out when the family’s income reaches roughly $15,490, reaching zero at approximately $52,918. This makes for one of the most gradual phase-outs in the welfare system.

Figure 3 illustrates what this would mean in combination for such a family of three. Families generally improve their financial well-being until they earn about $35,000. At that point, they would encounter a substantial cliff.

After an initial small hiccup, the family’s income would gradually increase at first. But once they reach roughly $35,000/year, there is a sharp, though reasonably shallow, decline, followed by a long period of decline. If the family earned $60,000/year their actual income would be no better than when they were earning little more than $12,000.

Figure 3

Another way to look at Iowa’s welfare cliff is to measure the difference between the income that a family on welfare would actually receive (combining benefits and earned income) with what they would hypothetically receive if there was no reduction in benefits as they earn additional non-welfare income. (Figure 4) Essentially, this is the tax burden they face as a penalty for earning additional income. That tax burden exceeds 50 percent at its worst.

Figure 4

This clearly represents a disincentive to work. Iowa is far from the worst state in terms of welfare cliffs, but reforming the system to reduce or eliminate welfare cliffs will go a long way to encouraging recipients to become self-sufficient.